archeology

THIS ISN'T A lion: It’s a miracle. You can almost hear the imperious growls that would have thundered in the imaginations of pedestrians approaching ancient Babylon’s Ishtar Gate. They would have walked along the Processional Way to enter the inner city, flanked by cerulean blue tile walls with 120 nearly life-sized lion bas-reliefs—a spectacle!

Not so in 1899, when German archaeologists arrived on the banks of the Euphrates—80 miles from Baghdad—and dug until 1917. Babylon’s splendor had been reduced to mounds of thousands of glazed brick fragments, which would fill nearly 800 crates sent to Berlin. There, each piece was laboriously cleaned, stabilized with modern material, sorted and assembled into whole bricks, and ultimately restored into panels of proudly parading beasts in Berlin’s Pergamon Museum. Iraq has been trying to get them back since the 1990s.

For nearly two centuries the Greeks and the British have been arm wrestling over the Parthenon Marbles—including a lengthy frieze of a mythical Greek feast, a muscled river god, and voluptuous female figures—taken from the Acropolis in Athens and now displayed in London’s British Museum. Lord Elgin was Britain’s ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, which encompassed Greece. Greece claims that Lord Elgin stole them, that the sale was illegitimate since Greece was occupied, and that they should be returned.

In the cliffs high above the Dead Sea archaeologists chip away with pick axes, hoping to repeat one of the most sensational discoveries of the last hundred years - the finding of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

The scrolls, a collection of manuscripts, some more than 2,000 years old, were first found in 1947 by local Bedouin in the area of Qumran, about 20 km east of Jerusalem.

They gave insight into Jewish society and religion before and after the time of Jesus, and spurred a decade of exploration, before the search fizzled.

Recent finds have stirred fresh excitement however, and archaeologists are probing higher and deeper than before. Hundreds of caves remain unexcavated and the experts are racing against antiquities robbers.

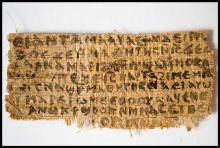

The Vatican's newspaper has declared the controversial “Jesus wife” papyrus fragment “a fake."

L'Osservatore Romano on Friday (Sept. 28) devoted two articles to Harvard professor Karen King's claim that a 4th century Coptic papyrus fragment showed that some early Christians believed that Jesus was married.

The announcement of the discovery on Sept. 18 made headlines worldwide but was met with skepticism by scholars who questioned the authenticity of the fragment.

In the Vatican daily, a detailed and critical analysis of King's research by leading Coptic scholar Alberto Camplani is accompanied by a punchy column by the newspaper’s editor, Giovanni Maria Vian, who is a historian of early Christianity.

Vian writes that there are “considerable reasons” to think that the fragment is nothing more than a “clumsy fake.” Moreover, according to Vian, King's interpretation of its content is “wholly implausible” and bends the facts to suit “a contemporary ideology which has nothing to do with ancient Christian history, or with the figure of Jesus”.

“At any rate, it's a fake,” he concludes.

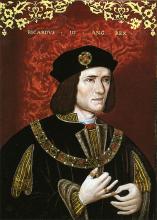

The hunt for King Richard III's grave is heating up, with archaeologists announcing today that they have located the church where the king was buried in 1485.

"The discoveries so far leave us in no doubt that we are on the site of Leicester's Franciscan Friary, meaning we have crossed the first significant hurdle of the investigation," Richard Buckley, the lead archaeologist on the dig, said in a statement.

Buckley and his colleagues have been excavating a parking lot in Leicester, England, since Aug. 25. They are searching for Greyfriars church, said to be the final resting place of Richard III, who died in battle during the War of the Roses, an English civil war. A century later, Shakespeare would immortalize Richard III in a play of the same name.

After his death in the Battle of Bosworth Field, Richard III was brought to Leicester and buried at Greyfriars. The location of the grave, and the church itself, was eventually lost to history, though University of Leicester archaeologists traced the likely location to beneath the parking lot for the Leicester City Council offices.