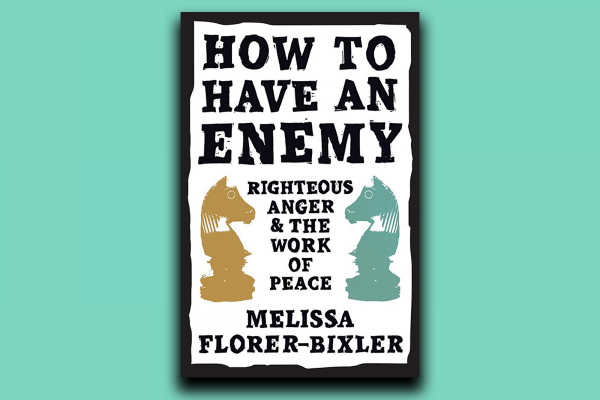

THE WORK OF peacemaking has been long beset by the stereotypes of it being “nice” work, polite to the point of being inoffensive. In her new book, Melissa Florer-Bixler wants to disabuse us of the idea that making peace means having no enemies. If anything, as she argues, Christians should have enemies well. Having enemies does not mean that the Christian who pursues justice incurs the resentment of others, but that their witness is direct, pointed, and takes sides.

The church, she writes, is “not to unify as a way to negate difference or to overcome political commitments,” but to sharpen those disagreements between the gospel and the world, particularly where reconciliation conceals power inequities. It does no one any favors, she suggests, to resolve moral disagreements within the church in a way that “disregards how coercion and force shape the lives of enemies.”

Read the Full Article