WHEN THE FULL Revised Standard Version of the Bible was released in 1952, the translation used “young woman” instead of “virgin” in Isaiah 7:14, which so enraged conservatives like Rev. M. Luther Hux that he publicly burned that page of the Bible. This would not be nearly the most impactful RSV translation, however, as the new film 1946: The Mistranslation That Shifted Culture seeks to explain.

1946 (named for the year the RSV New Testament was released) aims to measure the drastic effects of the RSV being the first Bible translation to use the word “homosexual.”

The film follows the research by Kathy Baldock and Ed Oxford on the RSV translation, with supplementary scholarship from other academics who help explain the RSV’s rendering of the Greek words malakoi and arsenokoitai as “homosexual.” It also traces the cultural ripples of this translation, which the film asserts helped anti-LGBTQ+ Christians demonize and ostracize queer people. Finally, it shows the relationship between the film’s director Sharon “Rocky” Roggio, a lesbian, and her father Sal Roggio, a conservative pastor.

Translating portions of the Bible can be tricky business. As scholars note, arsenokoitai is a word with few other uses across the ancient world and may have been invented by the apostle Paul. Literally, it is a combination word that means “man who beds with males,” connotating a sexual usage. Malakoi means “soft,” and is understood as referring to “effeminate” men.

In the American Standard Version, a common translation that preceded the RSV, the translation used for arsenokoitai is “abusers of themselves with men.” The RSV later changed its translation to “sexual perverts,” though at the time, this was code for LGBTQ+ people. After the RSV, the New International Version used “men who have sex with men,” while the New Revised Standard Version used “sodomites.” The NRSV’s Updated Edition, released in 2021, uses “men who engage in illicit sex,” while noting that the meaning of the Greek is uncertain.

1946’s central thesis is this: When the RSV translation committee erroneously chose to translate those two Greek words as “homosexual,” they gave conservative Christians (like Roggio’s father) a weapon to wield against queer people. That weapon multiplied (into the six so-called “clobber passages”) and restricted the possibility for Christians to follow along with the growing societal understanding and acceptance of homosexuality and other orientations and identities beyond heterosexuality.

The film is well-paced and produced, and it is grounded by a soundtrack from Mary Lambert, a Grammy-nominated artist and gay Christian writer and advocate. The film shines when it illuminates the complex work of translation teams.

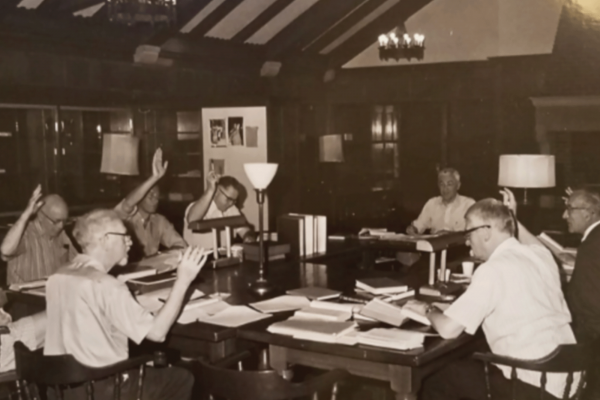

Historically and theologically, the work of Baldock and Oxford is compelling, especially their archival research into the RSV translation team and the gay seminarian, “David,” who challenged that team’s use of “homosexual.” The academics featured in 1946 help develop a richer understanding of the “clobber passages,” especially 1 Corinthians 6:9, although at times, the film (or perhaps the academics) overstate their case. Theologians continue to debate precisely how these verses ought to influence Christian sexual ethics. There is not one clear and obvious answer, despite the film’s presentation.

Unfortunately, by wrapping the movie in Roggio’s relationship with her father, 1946 awkwardly straddles a historical drama and autobiography. Worse, 1946 oversimplifies what is wrong with using the word “homosexual” in the Bible. In doing so, it offers a thin defense of queer people that anti-LGBTQ+ Christians will find easy to knock down.

It is important that today we say clearly that the word “homosexual” does not belong in the Bible. As scholar David Bentley Hart writes, “the ancient world possessed no comparable concept of a specifically homoerotic sexual identity.” The Bible does not condemn any sexual orientation as we understand it today. As Hart says, in 1 Corinthians 6:9 the word arsenokoitai would “refer to a particular sexual behavior, but we cannot say exactly which one.” On this alone, 1946 makes a critical injunction against the misunderstandings of biblical sexual ethics. But this is where the usefulness of documenting the “mistranslation” ends.

For example, 1946 papers over how the definition of “homosexual” has changed in the 80-plus years since the translators worked on 1 Corinthians.

The RSV translation team started work on 1 Corinthians in the 1930s. At the time, “homosexuals” were widely believed to be predators and potentially mentally ill. As gross and incorrect a characterization as that is, it is close to what translators would have seen when trying to translate arsenokoitai. Baldock told Sojourners that contrary to how it may seem, “there was no malice attached” to the translation team’s decision.

Just as we must read the Bible in the context of ancient Greco-Roman society, we also must read different translations in the context of the culture from which they were produced.

Of course, not everyone bought into this period’s vilification of queer people, particularly not queer people themselves. David, the gay (privately at the time) seminarian, challenged the RSV translation in the 1950s, using in part his better understanding of LGBTQ+ people. David had an important dialogue with Luther A. Weigle, head of the translation committee, and the decade between his challenge and the second edition of the RSV is worth unpacking, as it helps explain both the evolving understanding of the term “homosexuality” and the work of translation teams.

But the film drastically oversimplifies this to “David challenged the translation, Weigle admitted he was wrong, but it wasn’t fixed until 1969.” This is a disservice to the RSV translation team, and to Baldock and Oxford’s research.

Baldock was kind in explaining the difference between her research and the film: “You can’t do all of this background in a 90-minute movie.” But this is charitable, since Baldock covered this same background in the first 12 minutes of our interview.

Perhaps 1946 wouldn’t have flattened such an interesting history if it weren’t also trying to tell the story of Roggio and her father. With respect to both Roggios — who seem to be doing their best to love each other despite their disagreements and tension — scenes between the two are often awkward and painful; it’s unclear if this is intentional.

The film’s crescendo is just as suspect. Built from Baldock’s previous presentations, the movie compellingly connects the RSV’s use of “homosexual” to the rise of the Religious Right, the scapegoating of LGBTQ+ people during the AIDS crisis, and more. But it presses too far when it suggests that, if not for the mistranslation, anti-LGBTQ+ bigotry wouldn’t be more common in the church than outside it.

Whether 1 Corinthians 6:9 said “homosexual,” “sexual perverts,” or “abusers of themselves with mankind” as it does in the King James Version, anti-LGBTQ theology would have still existed. Then, as today, nonaffirming theologies are rooted in much more than “clobber passages.” Affirming Christians would do well to understand these arguments and articulate both careful, forceful opposition and an inclusive sexual ethic crafted from what the Bible positively teaches.

If there is a hope for including queer sex in Christian sexual ethics (and there is) it must not rest on dismantling a few bad translations.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!