Bill Hybels, Senior Pastor for Willow Creek Community Church, spoke out last week on the ongoing Ferguson protests. In the video, shared this week by Willow Creek Church-affiliated artist group The Tungsten Collective, Hybels calls on people of faith to listen to the pain and hurt expressed by many since the August shooting of Michael Brown.

He quotes James 1:19, urging people of faith to “be quick to listen, slow to speak.”

Hybels has spoken out on racial reconciliation for years, and here underscores one reason why reconciliation work is often so difficult.

“It’s just so much easier to live in your own story than it is to try to understand the narrative of the other,” Hybels said.

Indeed, when it comes to interactions with law enforcement, the black experience and the white experience in America are “two totally different narratives [that often] … don’t touch each other until a Ferguson happens,” he said.

At one point the megachurch pastor emphasizes — almost uncomfortably lightheartedly — just how untouched he’s been by fear, crime, and violence in his neighborhood.

“[Peace] is all I’ve ever known. I’ve never had a single adversarial experience with a law enforcement officer in my entire life,” he said.

But in drawing a distinction in the difference of experience, he echoes a Jia Tolentino column in TIME earlier this fall on how social divisions are revealed based on which evils we mourn and pledge to fight against. While Hybels falls short of explicitly naming a power and privilege differential, he urges humility, listening, and seeking understanding among people of faith — all the more resonant today after the non-indictment ruling on the choking death of Eric Garner.

WATCH the full video here.

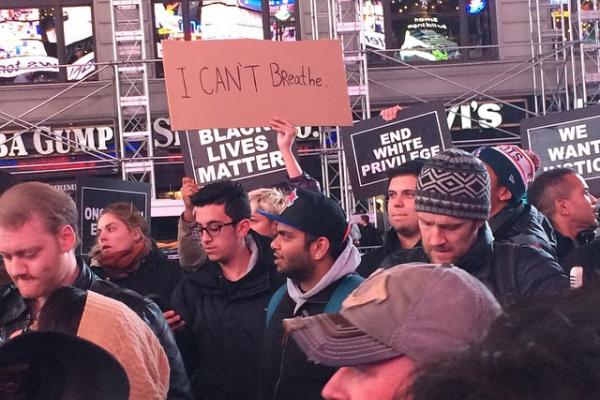

I was in Ferguson Wednesday when it happened: In a morally stunning decision, a Staten Island grand jury announced it would not bring criminal charges against a white police officer who choked a black man to death during a brutal incident last July. Stopped for allegedly selling some loose and therefore untaxed cigarettes, officer Daniel Pantaleo put a “chokehold” on Eric Garner, despite the fact that the move is against NYPD rules. Video of the incident shows Garner uttering his last words, “I can’t breathe.” New York’s medical examiner officially called this a “homicide,” but the grand jury said no charges will be made.

Of course, this comes just 10 days after the Ferguson grand jury decision not to indict another white police officer, Darren Wilson, for fatally shooting an unarmed black teenager named Michael Brown on Aug. 9. Sojourners had convened a retreat in Ferguson for both national faith leaders and local pastors to look deeply at the historical and theological foundations of the Ferguson events and reflect upon how the church must respond. Emotional calls from pastors in New York City came with the horrible news, and people just began to weep — one young man wailing, “This time it was all on video …. and it still didn’t matter! How can I as a black man bring a black son into this world?” Lament and prayers followed with a resolve from an extraordinary two days on the ground in Ferguson — to act.

Local experts in St. Louis County helped us understand the damage done to their local communities for decades that led to the response that erupted after the killing of Michael Brown. We walked silently and prayerfully alongside the memorial to the slain teenager on West Canfield Avenue with black parents imagining their own sons lying there, and white parents realizing this would never happen to our kids. We kept looking at the street where this bloody incident had taken place, feeling more and more doubt about the narratives the county prosecutor had used to exonerate and excuse the white police officer from any responsibility — or at least a trial to publically sort out “conflicting testimonies.”

We met in a church with seven young leaders of the Ferguson protest movement. In just 116 days, these young people had become self-educated and extraordinary leaders, and we listened to a compelling analysis of their urgent situation and how they were trying to apply the history of social movements to change their oppressive circumstances. Their chilling stories of police harassment and brutality, preceded by a narrative of the educational and economic brutality that black young people like them experience daily were transforming words for those of us who listened, spellbound. As I listened, I realized America would be converted by these young people’s honest and earnest conversation — they would win the national debate about our criminal justice system’s response to young people of color.

There’s this microaggression happening online, offline, and all around that has a nice sentiment, but really needs to stop. Can we call for a week-long moratorium on decrying “ALL LIVES MATTER?”

This is a request specifically for my white brothers and sisters, especially those in the church.

I, of course, as a white heterosexual married middle-class highly educated American male, believe that all lives matter. It’s something I’ve been fighting for my entire adult life. Whether it is the mother infected with HIV by her wayward husband in western Africa, whether it is the undocumented immigrant father who may be separated from his American-born children, whether it is the NRA card-carrying white uncle who does an honest job and is a good neighbor back in the midwest, whether it is the homeless thirty-something woman coming off a bad meth addiction but needing shelter during a difficult winter, of course, by all means, every life matters.

Your life matters. My life matters. All lives matter.

This is a non-negotiable. This is true. This is what it means to be made in the image of God, as we’re told in the Book of Genesis — everyone, whether you’re white, black, brown, male, female, straight, gay, bisexual, transgender, Republican, Democrat, rich, poor, nice, kind of a jerk, young, old, middle-aged, we all matter.

But these past couple weeks — these past four months, five months, 22 months? — it’s important that we stand with the ever-growing chorus and declare, yes, black lives matter. With the heartbreaking, soul-wrenching death of Michael Brown, the news just yesterday of another non-indictment in the death Eric Garner, or the dark night when Trayvon Martin was shot down in Florida, a chorus of voices has risen to declare with one voice and hashtag that #BLACKLIVESMATTER.

After the monsoon, after work, I catch

you with your face in the hot laundry,

the syntax of spring held together by sap,

hanging wild and worried and crazy

in the lowest branch. In the ripe country,

salmon fold over the linens of the bay,

and I weep with you from the shore, embodied.

For still you feel the fell of dark, not day.

Just over one week after a grand jury elected not to indict Darren Wilson for the killing of Michael Brown, a Staten Island grand jury has cleared an NYPD police officer of any criminal charge in the death of Eric Garner.

The officer, Daniel Pantaleo, a white male, choked Mr. Garner to death as other police officers stomped on his head. Mr. Garner, 43, suffered from asthma and was suspected of illegally selling cigarettes.Along with other evidence, the grand jury viewed a video recorded by bystanders, which fully captured the violent arrest.

It probably can’t. It may help you ponder the kind of person you hope to become, and it might even help you orient yourself towards the next few baby steps you take in this life, but decide what you want to do with your life? Not likely. None of us ever really decides ‘what to do with our lives,’ as if that were some golden tablet plucked out of the heavens. But that won’t stop us from frantically stressing.

As a recent college graduate who does indeed stress about such a question, I recently rediscovered the modern classic that is Good Will Hunting as I spent Thanksgiving anxiously deliberating my future — and realized it has a lot to offer.

Although the film is perhaps most famous for pulling heart strings, it is also a deep exploration of courage and humility. It forces viewers to question their vocational priorities and even invites reflection upon why we choose to seek, or avoid, outward success. If you haven’t seen this 1997 drama, and you’re stressed about what to do with your life, you should stop reading now and go watch it before I start dropping spoilers.

The Supreme Court — the last stop for condemned prisoners such as Scott Panetti, a Texan who is mentally ill — and whose case was just stayed by an appellate court — appears increasingly wary of the death penalty.

In May, the justices blocked the execution of a Missouri murderer because his medical condition made it likely that he would suffer from a controversial lethal injection.

Later that month, the court ruled 5-4 that Florida must apply a margin of error to IQ tests, thereby making it harder for states to execute those with borderline intellectual disabilities.

In September, a tipping point on lethal injections was nearly reached when four of the nine justices sought to halt a Missouri prisoner’s execution because of the state’s use of a drug that had resulted in botched executions elsewhere.

And in October, the court stopped the execution of yet another Missouri man over concerns that his lawyers were ineffective and had missed a deadline for an appeal. The justices are deciding whether to hear that case in full.

In the beginning, there was “Noah.”

Coming up, there’s “Exodus: Gods and Kings,” an update of Cecil B. DeMille’s classic for this generation.

And that’s not all. On Dec. 7, Lifetime’s miniseries “The Red Tent” premieres.

God is smiling on Hollywood.

The adaptation of Anita Diamant’s blockbuster novel (and perennial reading group favorite) is an expansion and interpretation of the story of Dinah from the book of Genesis.

I have not seen “The Red Tent,” though I have read Diamant’s book. But its airing could not be more timely — the same week as Jewish congregations are reading the story of Dinah from the Torah.

There is something else that makes “The Red Tent” timely — tragically timely, in fact.

Within the past three months tremendous strides have been made toward protecting our earth. The People’s Climate March drew hundreds of thousands of people to the streets of New York City to advocate for climate action. The Keystone XL pipeline failed to pass the U.S. Senate. The United States and China passed a joint agreement to limit their greenhouse gas emissions.

This week there is great hope that progress will continue.

The Lima conference is seen as the last-stop in a series of slow moving international conversations leading up to the 2015 UNFCCC conference, which will happen next December in Paris. The ultimate goal of this climate-focused body of the United Nations, which has met for nearly two decades, is to have the nations of the world sign a landmark climate change agreement that drastically reduces greenhouse gas emissions country-by-country.

With Paris a year away, Lima is being called a hopeful stepping stone in this process.

Beyond the Letter of the Law: The Jewish Perspective on Ethical Investing and Fossil Fuel Divestment

Climate change resulting from the use of fossil fuels poses a grave threat to human and non-human life. Because a real national response to climate change has been stymied by political inaction, cultural inertia, and the concerted effort of fossil fuel companies, environmental organizations have encouraged universities, towns and cities, religious communities and other organizations to divest from fossil fuel investments.

In Judaism, ethical investing is part of traditional Jewish morality. Within the sources are two questions that are central to the issue of divestment:

Is it mandatory to divest from products (like tobacco and fossil fuel) that are not illegal but are, clearly, harmful?

To what degree is a minority shareholder morally responsible for the actions of a corporation when they are unable to exercise any significant control?

Several fundamental Jewish theological concepts bear upon these questions. Firstly, since God created the universe only God has absolute ownership over Creation (cf. 1 Chronicles. 29:10-16). Humans do not have unrestricted freedom to misuse Creation as they are tenants, not owners. Since human ownership of Creation is not absolute, the use of even private property cannot be divorced from morality. A product may be legal, but if it is harmful, its use is not ethical.