The top 10 or 20 bestselling books at Amazon.com vary slightly from hour to hour, day to day, but one thing remains pretty constant: There are always several books on spirituality, often with Protestant evangelical leanings; and there are always books on diet, promising either dramatic weight loss or astounding well-being through some “revolutionary” plan.

Even within the category of “Religion and Spirituality,” some of the most popular books focus on diet and bodily health, and when they don’t, they focus on happiness via the most direct route. They’re all about “how to be successful and happy,” “how to make miracles happen,” and “how to know that there really is a heaven, and that you’re going there.”

Having been a skeptic for as long as I can remember, I’ve never had much patience with those books. If books (and checkout-stand magazines, for that matter) really held the secrets for people to “get skinny by this weekend” or “beat cancer with these super-foods,” why did people from my church choose gastric bypass surgery, and why did my father (a pastor) perform so many funerals for the non-survivors of cancer? And if miracles could happen, and people could find success, happiness, and assurance of a place in a heaven that’s “for real,” why, throughout the course of my pious Bible-reading upbringing, did I never seem to find anything in the Bible that sounded remotely like that?

"Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons [and daughters] of God.”

Matthew 5: 9 from the Beatitudes

I grew up watching casualty reports from the Vietnam War on TV. My Uncle Bill, a lieutenant colonel in the Air Force, was serving there. My family watched the news every evening to learn about the latest casualty reports. I was too young to understand the anxiety of my parents, but I felt the tension while Uncle Bill was deployed.

As an adult, it’s been a different story. I understand and experience things more fully and have an emotional connection to what I see and hear. That has been true for the last decade. Ten years ago, the Iraq War began. Ten years marked by conflict, violence, and loss. Ten years of debate about why we went to war and why we remained. Ten years dealing with death and injury – 4,488 U.S. deaths and 32,321 soldiers coming home with significant injuries. Suicide rates of soldiers are so high it is impossible to ignore – some while in Iraq and others after returning home. Traumatic brain injuries, grieving families, moral injury, and multiple limb loss are just a few of the constant reminders of the tremendous costs of war. The toll on the nation’s economy has been long lasting as well. The jobless rate among veterans is staggeringly high.

The human toll has been significant. But military personnel aren’t the only causalities of this war. Numbers vary, but statistics tell us more than 100,000 Iraqi citizens also have been killed and nearly 3 million have been displaced.

These figures cannot be ignored. And they are the results of war.

What would an “atheist Lent” look like? A group of young nonbelievers are finding out, observing the Christian practice minus its religious context.

They have given up alcohol, animal products, and various Internet and cellphone interactions. One has vowed to make a daily Lenten practice of telling those he encounters how important they are to him.

But their observance of the 40-day period in which many Christians abstain from worldly desires in a bid to come closer to God has upset some atheists who say borrowing religious traditions is antithetical to nontheism.

The exercise has also illustrated a divide in the nontheist community – between older atheists who see religion as inherently evil and younger atheists who are more open to interactions with religious belief.

(Note: This post contains some frank and graphic discussions of sex and sexuality.)

Two boys from a Steubenville Ohio high school (I’ve opted not to use their names, though they are readily publicized by other media) have been sentenced to time in a juvenile detention center for the rape of a 16-year-old classmate who was reportedly so drunk at a party that she could no longer stand on her own. Aside from “digitally” raping the girl with their hands, reportedly multiple times, one of the boys took photos of the girl without her clothes, shared them via social media, and both young men bragged about the incident to their social networks following the incident.

As the father of both a boy and a girl, I was particularly angered and disturbed by this story. The very fact that such things happen in a supposedly civil society is a stark reminder that we have only a tenuous hold on the well-being of our kids once they leave our sight. We can only hope and pray that we’ve empowered them with the sense of autonomy, respect, compassion, and restraint to keep them either from becoming victims of such violations, or perhaps even perpetrators of it themselves.

But once I get beyond my initial feelings about the whole situation, I’m left wrestling with a number of questions that still feel terribly unresolved.

I try to be a diplomat, to err on the side of patience, when it comes to theological differences between Christians.

Reconciliation and peacemaking come natural. My wife says I stop sounding like myself when I'm hard-nosed or critical.

But recently, sitting across from a young man who heroin ("that boy") very nearly got the better of just days before, I lost at least a layer of my irenic self, lost a bit of my cool. When it comes to certain teachings, I'll not be as diplomatic in the future.

When are we going to stop teaching that the Father has to look on Jesus to love us? Why do we teach that the Father turns away from us, abandons us because of our sin? When are we going to stop teaching that the Father is angry with men and women or hates us (or stop projecting any other merely human emotion on to God?), conveying by our messages (verbal and nonverbal) that God despises that which he gloriously made in God's image?

The message we too often send is that Jesus must persuade the Father to love us, must plead with his Father not to forsake us.

Last Sunday night, the Rev. Thomas Rosica was walking through the Piazza Navona in Rome’s historic center when he bumped into Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio, who he has known for years. Bergoglio was walking alone, wearing a simple black cassock and he stopped and grabbed Rosica’s hands.

He had reason to be worried. Two days later, on Tuesday evening, he and 114 other cardinals entered the conclave to elect a successor to Benedict XVI; a little more than 24 hours and five ballots after that, Bergoglio emerged on the balcony of St. Peter’s Basilica as Pope Francis. “I want you to pray for me,” the Argentine cardinal told Rosica, a Canadian priest who was assisting as a Vatican spokesman during the papal interregnum. Rosica asked him if he was nervous. “A little bit,” Bergoglio confessed.

It was a surprising outcome, and even if Bergoglio suspected something was up, few others did, including many of the cardinals in the Sistine Chapel with him.

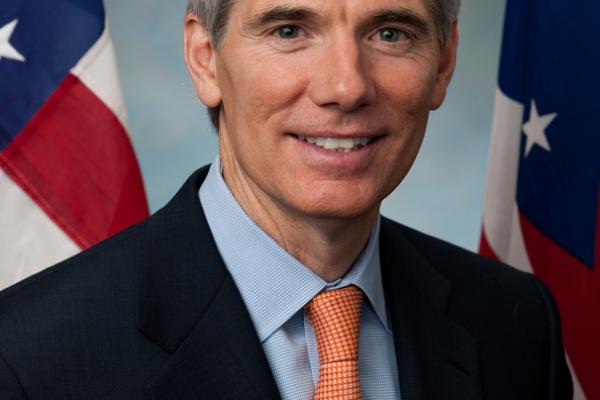

Republican U.S. Sen. Rob Portman on Thursday announced he has reversed his longtime opposition to same-sex marriage after reconsidering the issue because his 21-year-old son, Will, is gay.

“It allowed me to think of this issue from a new perspective, and that’s of a Dad who loves his son a lot and wants him to have the same opportunities that his brother and sister would have — to have a relationship like Jane and I have had for over 26 years,” Portman told reporters in an interview at his office. Portman said his son, a junior at Yale University, told his wife, Jane, and him that he’s gay and “it was not a choice, it was who he is and that he had been that way since he could remember.”

The conversation the Portmans had with their son two years ago led him to evolve on the issue after he consulted clergy members, friends — including former Vice President Dick Cheney, whose daughter is gay — and the Bible.

Religious freedom activists scolded the U.S. State Department for not appearing at a hearing Friday on Iran’s treatment of religious minorities, and called for greater government action to secure the release of people imprisoned there for their faith.

“The State Department is AWOL — they are absent without leave,” complained Jay Sekulow, chief counsel of the American Center for Law and Justice, a conservative law firm that represents the wife of Saeed Abedini, an Iranian-American minister in Tehran’s Evin prison. “They act as if they are embarrassed about Mr. Abedini’s faith.”