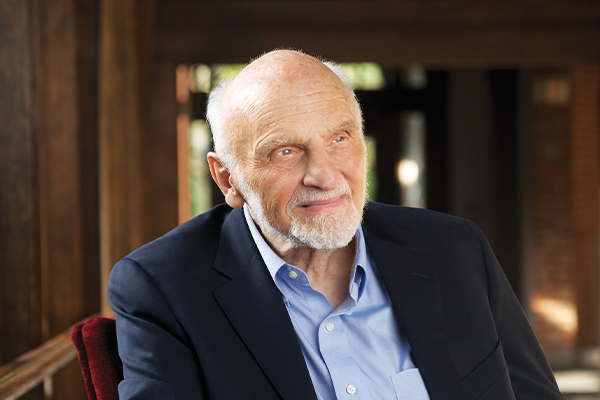

WALTER BRUEGGEMANN, THE much-beloved biblical scholar and author, died at the age of 92 on June 5. As one speaker at his July 19 memorial service noted, since his death there have been thousands of words written in tribute to Brueggeman in publications (including by Sojourners president Adam Russell Taylor on sojo.net) and on social media. We are add-ing to that word count because of how important Brueggemann has been to us at Sojourners — he has been one of our guiding lights and became a contributing editor in 1989. He was one of several people who helped Sojourners sustain and refine our founding belief that to follow Jesus and live lives shaped by scripture and prayer was intertwined with a commitment to social justice and concrete works of mercy. He indirectly mentored many of us in how to keep the Bible as a living, provocative force shaping our personal integrity, our spiritual growth, and our public witness.

Read the Full Article