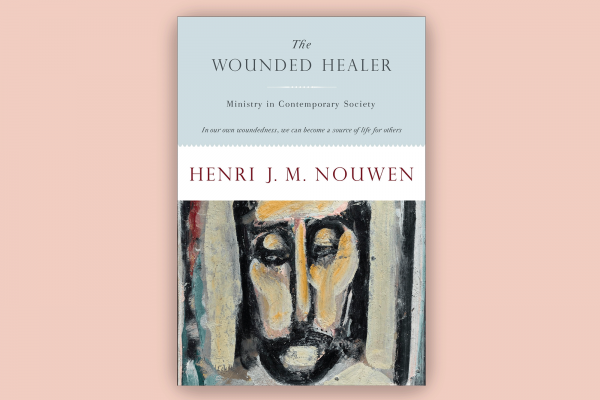

IN THE WOUNDED HEALER: Ministry in Contemporary Society, Catholic theologian and priest Henri J.M. Nouwen analyzes how the church fails to address the heart of our collective pain and longing. Nouwen presents a paradigm for renewed Christian leadership and care founded on the archetype of the “wounded healer.” More than 50 years after the publication of The Wounded Healer in 1972, we continue to struggle — both individually and societally — with the “wounds” Nouwen names: alienation, separation, isolation, and loneliness. Whether we’re ministers or not, we need the gentle wisdom of the wounded healer to build a more loving, just world.

While the concept goes back at least as far as Plato, the term “wounded healer” was coined by psychoanalyst and doctor Carl Jung. To demonstrate the link between personal suffering and the capacity to care for others, Jung draws on the Greek myth of Chiron. Chiron is a centaur who, due to severe physical pain, becomes an important healer and teacher. Nouwen extends this principle to ministry, calling for church leaders to cultivate “a deeper understanding of the ways in which [they] can make [their] own wounds available as a source of healing.” For both Jung and Nouwen, this work develops depth and compassion. Nouwen writes, “For a compassionate [person] nothing human is alien: no joy and no sorrow, no way of living and no way of dying.”

Read the Full Article