Sep 23, 2021

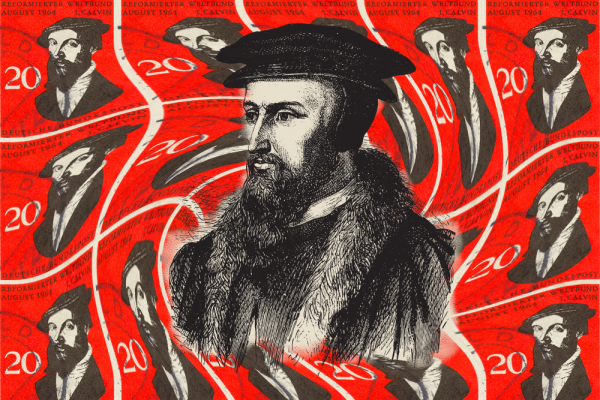

As a post-evangelical, I have no interest in rehabilitating Calvin’s ideas about double predestination or his justification for the execution of Michael Servetus. Nonetheless, I’m unwilling to cast Calvin and his theological legacy in exclusively negative terms; I believe that confronting racial injustice today actually requires recuperating Calvin’s infamous doctrine of “total depravity,” or a spiritual condition staining humanity from birth. Doing so can help us better understand why both progressive and reactionary heirs to Calvinist thought fall short — and how we might work to transform our fallen world instead.

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login