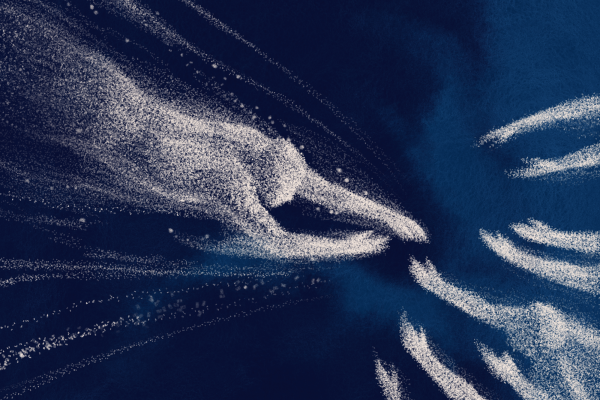

WE KNOW WE intertwine with one another and the rest of creation in ways both material and symbolic: through blood and law, employment and play, through the full range of physical contact and social niceties, as well as loan papers, traffic tickets, and contracts. We sing a hymn in church, and the song swells into harmony, a gift of complexity and cooperation.

Through it all we breathe: Breathe in. Breathe out. My breath out mingles with your breath in. A communion of droplets. And so clusters of COVID-19 come not just in places of forced confinement—prisons, nursing homes, meatpacking plants—but after birthday dinners and choral practice, weddings and retirement parties.

“We’re all in this together” you might have heard as stay-at-home orders spread across the country; “the virus is the great equalizer.” After all, what could be more universal than breath? A pauper or a prime minister might breathe in a sufficient viral load to become critically ill.

Labored breathing

BUT THE CONDITIONS in which we breathe, the condition of our breathing bodies, and the conditions of the facilities that treat our bodies when breathing becomes difficult are rarely equal. Some people of great wealth have died from COVID-19, but many, many more of modest or little means have perished from it.

Societal inequalities of income and race incarnate as preexisting medical conditions, including diabetes, asthma, high blood pressure, and kidney and pulmonary disease, that increase the risk of severe illness and death from COVID-19. For example, in Washington, D.C., the bottom 10 percent of income earners have a rate of diabetes nearly 74 percent greater than the median. The wealthy can pay for better food and housing; they have less stress and exposure to industrial pollutants and more access to recreation spaces and health care. The lowest-paying jobs, many of which force people into overexposure to the virus, are disproportionately filled by those with options limited by racial bias and legal status. As Adam Serwer wrote in The Atlantic, “Black and Latino workers are overrepresented among the essential, the unemployed, and the dead.”

And the pandemic did not stop the other ways we deprive people of the breath of life: A neighborhood lynch mob stalks, films, and kills jogger Ahmaud Arbery but is not charged for months; police officers shoot Breonna Taylor in her own home during a botched raid; a white cop kneels on George Floyd’s neck for 8 minutes and 46 seconds.

I breathe out. You breathe in. Before coronavirus, some people did that without a second thought. Yet every day others were struggling to breathe at all.

Read the Full Article