In history classes across the United States, students are taught that the persecution of Christians was foundational to the independence of this country. But after almost a quarter millennium, the majority of evangelical Christians still believe Christians experience discrimination. This belief persists, despite the fact that Republican Christian presidents have occupied the White House for 30 of the last 50 years and that there’s a conservative majority on the Supreme Court. In short, this would seem like empty virtue signaling. More tangible claims of persecution against the global Christian church litters recent history, though, and one can draw lessons from its aftershocks in examining the true calling of a Christian life.

Take Lviv, Ukraine, the country’s cultural capital in the West. Visiting Lviv today, one can’t help but notice the overwhelming number of churches. But unlike in some of the cities farther west that inspired Lviv’s Hapsburg streetscape, the churches here teem with life, prayer, and joy. Bells ring, incense burns, and choirs sing at all hours. You can’t miss the signs of piety: people stopping on the sidewalk to bow in front of churches, a short prayer said on a crowded city bus while passing a procession, prayer cards and well-wishes crammed into window panes.

img_3028.jpg

But it wasn’t always like that.

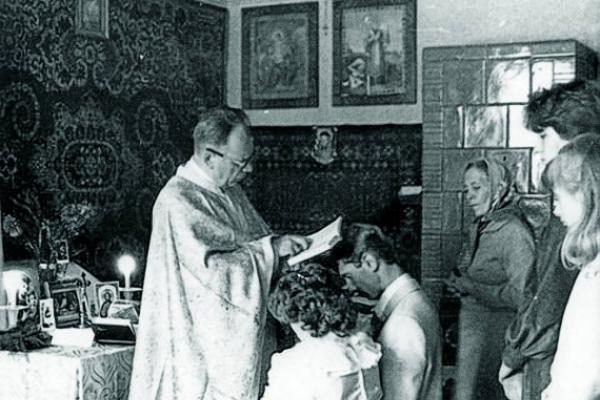

Decades ago, most of those church buildings only vaguely resembled houses of worship. Some were used as military barracks and warehouses, while others served as theaters and libraries. Before 1989, people’s piety wasn’t on display, and prayer happened in secret. This dramatic shift is just one chapter in the history of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, the dominant church of Western Ukraine.

Orthodox in doctrine and Catholic as a matter of universality, the church has outlived a half dozen empires and several continental wars in little over a millennium. From 1946 to 1989, the church was outlawed in the Soviet Union, which had annexed Lviv and the surrounding area after winning WWII. The Soviets brought with them state atheism, driving most Christians (though not all) underground.

Iryna Kolomyyts, 61, a blissful woman who used to run the pastoral program at Ukrainian Catholic University’s Institute of Church History, has experienced this underground church firsthand. She told Sojourners about secret gatherings in thick forests where thousands of her peers would come to listen to their local bishop and take communion.

“Persecution weeded out those who didn’t have faith in our gospel’s truth,” she said, acknowledging that her generation grew up only knowing an underground church.

Her father was also arrested for leading a Ukrainian Greek Catholic Community in a suburb of Lviv and spent nearly a decade at a Soviet Labor camp in Kazakhstan.

Kolomyyts said that the church was persecuted for its deep association with indigenous Ukrainian culture — a deviation that threatened the hateful Soviet ideology set on erasing diverse experiences.

Soviet Dictator Joseph Stalin believed in the Russian cultural dominance of the Soviet Union. As a young revolutionary, he argued that “the demolition of national barriers and close unity between the Russian, Georgian, Armenian, Polish, Jewish and other proletarians is a necessary condition for the victory of the proletariat of all Russia.”

“[The Soviet Union] presented a compromised public morality, one where the only ‘truth’ presented was a lie to serve ideology,” Kolomyyts said. “The faith provided an anchor for what was true and good at a time when we didn’t know what was going on in the world.”

Learning to Pray in Secret

The evangelist Matthew recounts Christ’s teaching to pray in secret, to anoint one’s head, and to live a public life bearing Christian witness through example. Some aren’t fortunate enough for that kind of Christian lifestyle to be a choice. It’s a matter of survival.

Although many white evangelical Christians in the U.S. aren’t in an literal battle of survival at the hands of an organized, coordinated, and powerful cabal, many feel that they’re being discriminated against, with some arguing that opposition to certain civil rights protections amounts to state persecution. Most of that perceived persecution falls along partisan and racial lines: White Republicans stand alone in believing their persecution is the total inverse of black, Muslim, queer, and other marginalized experiences. But the loss of cultural capital and social ubiquity is not persecution. A bathroom bill does not amount to the bombing of Egyptian Copts, and the “War on Christmas” does not amount to Hindu nationalist lynch mobs targeting Christians in India.

img_4924.jpg

In fact, the United States doesn’t make any list of any scientific study detailing religious persecution, from Pew, to Aid to the Church in Need, to Becket Law, to its own State Department.

But these actions and white evangelicals’ organizing around political institutions creates a kind of privileged Christian hegemony that stifles justice-oriented groups, isolating them from one another.

This was the opposite during the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church’s underground period — interpersonal relationships were emphasized as the only means of evangelization. Communities gathered in “apartment churches,” much like the ones springing up today in Cuba and China. Parish councils, bookkeepers, and congregational constitutions weren’t needed when “two or three gather in Jesus’ name.”

Perhaps, then, instead of out-organizing the organized [... state, hegemon, empire, soviet socialist republic, whatever], organic, Christian disorganization is what will save a truly truth-and-justice-oriented Christianity.

That’s the working thesis of Justin Tse, a religious scholar who specializes in Chinese Christian communities. In 2016, Tse formally joined the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, in part because of its recent memory as an underground church.

“We are much better at the informal aspects of being a community than we are at navigating institutional procedures,” Tse said.

That means radical lay initiative keeps the church running, leaving administrative questions for later.

But there are some drawbacks. To this day, most Ukrainian Greek Catholic parishes don’t have any sort of online presence or up-to-date prayer books. Phone numbers are rarely listed, and, like in the underground church, visitors often need an ‘in’ to figure out what’s going on when and where. One thing’s for sure, though: The people praying the hardest can often be found at the most off-the-grid parishes.

“Here, I think Benedict XVI and Dietrich Bonhoeffer make an odd coupling, as both have made intimations that a smaller church with less bureaucracy could probably encapsulate what it means to be the people of God,” Tse said.

The Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church has that, almost despite itself. To paraphrase Benedict XVI, Bonhoeffer, and the Ukrainian Catholic University motto, ‘Just do it’: Just pray. Just organize.

Leadership in the Underground

It’s not that the underground church didn’t have a hierarchy or institutional structures. Apostolic succession and the importance of Rome are perhaps the biggest reasons that the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church didn’t fall to a false unification synod with the Russian Orthodox Church in 1946.

The Russian Orthodox Church enjoyed limited privileges after being legalized by Stalin on the condition that it work closely with Soviet security services. Underground Ukrainian bishops issued epistle-like decrees to the network of apartment churches, and pastors deferred to a clearly understood tradition when contact with other churches was too risky. What was centered, though, was Christ.

622431_10151009128446430_263582296_o.jpg

The days of persecution for the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church are largely behind it. Save for anti-Catholic policies by pro-Russian rebels in Crimea and Ukraine’s occupied eastern regions, the church in Ukraine is going on strong. But as countless alarmist news articles have said, Christianity is rapidly declining the further west you travel from Lviv — even among Ukrainian Greek Catholics.

“[The] church in the U.S. is indeed getting smaller. What does small mean? Small and insignificant? Or small and dynamic — dynamic in mutual love?” asks Borys Gudziak, the current Archeparch of the Ukrainian Catholic Archeparchy of Philadelphia.

Before becoming a bishop, the American-born Gudziak spent the 1990s in Lviv as a layman laying the groundwork for the Ukrainian Catholic University’s renewal after also being dismantled by the Soviet government.

The challenge Ukrainian Greek Catholic leaders face today is losing sight of the underground church’s insights now that almost 5 million believers are able to pray publicly.

“If we can be counter-cultural, live without fear regarding our size or numbers, hear God’s word, listen to His voice and have communities that are iconic — showing through our lives that love of God and love of neighbor are fundamental for us — we will fulfill our vocation, in the U.S. and elsewhere,” Gudziak said.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!