Popular American mythology holds that power in this society is rooted in the sovereign people. This concept runs through American history. It is probably most often found today in ninth grade civics classes and in the speeches of aspiring politicians. This sovereign power is exercised by people coming together and discussing their common problems. Interest groups of various sorts are formed, which have a voice in the political process. The political process is seen as these interest groups coming together and forming coalitions and counter-coalitions, with the will of the majority ruling in the interests of all.

More realistic is the commonly heard assertion, "You can't fight City Hall." Many Americans, perhaps now a majority according to recent polls, believe that individuals have no voice in the decisions that ultimately affect their daily lives. The resulting apathy, exemplified by the large numbers who do not bother to vote, is more prominent than ever since Watergate. People are openly expressing the belief that all politicians are corrupt; consequently, why bother to get involved?

However true the belief in universal political corruption is, it profoundly misses the point about the way power is exercised in American society because it sees the source of power residing ultimately in the political process. This question of the structure of power is a crucial one, because it significantly affects the way Christians live out their lives in the world, corporately and individually.

THE POWER ELITE

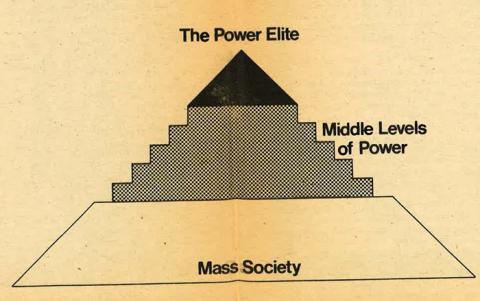

Anyone studying the structure of power in the United States must acknowledge a great debt to C. Wright Mills. His The Power Elite, written in 1956, is the seminal study of the national power structure. (Full bibliographical references for this and other works will be found at the end of the article.) His conclusions have been vehemently attacked by those who disagree with his conclusions and substantially modified by those who agree with his framework. However, even with the refinements and modifications, Mills' descriptive framework remains the best starting point for discussing power and its national manifestations. Power in America can be best understood in a hierarchically stratified framework. In this case, a picture is worth, a thousand words:

As the diagram shows, at the top level of the distribution of power, there is a small Power Elite, which can be conceived of as a Governing Class. (For distinctions between the Governing Class and the Power Elite, see the essays in Domhoff and Ballard, C. Wright Mills and the Power Elite, and Domhoff's discussion in Higher Circles; there are distinctions, but for the purpose of this article, they are not significant.) The power elite, according to Mills, consists of corporate, political and military representatives, with each group exerting independent influence, none having the ascendancy. The Middle Levels of power contain such groupings as the Congress, Mayor Richard Daley, and the various 'powerful' interest groups. This is the level of power that is supposed to connect the will of the people with the significant decisions made on the national level. The Mass Society is probably an inappropriate term, because American society does not yet portray all the characteristics social scientists associate with the concept, but mass society is a more fitting description than the common assumption that individual citizens do have a voice in decision making through their participation in voluntary organizations.

The major modification that has been made in Mills' argument has been to his description of the composition of the power elite. Mills saw none of the three groups that compose the elite as having the ascendancy. It is clear now, following the work of people like Ralph Nader, Domhoff, Kolko, Newfield and Greenfield, plus a host of others, that there is corporate dominance within the power elite. This is one reason that the question of whether there is a power elite or a governing class is somewhat inconsequential. While the distribution of income to different strata in society has remained almost constant over the past sixty or seventy years, (See Kolko, Wealth and Power in America), there has been an increasing concentration of wealth and the means of power at the corporate level, especially since World War II, and especially in the large corporations (the Fortune 500), most of which are heavily involved overseas and most of which have been significantly involved in production for the war machine. It is the increasing concentration of wealth and power by the corporations that has led to the corporate dominance of the power elite, and consequently the domination of the means of power in American society.

This corporate dominance is not to be understood in terms of a cold, impersonal machine grinding out decisions. Individuals lie behind the exercise of corporate clout, and the individuals at the top who shape the basic decisions and thrusts of action in society form a cohesive class interest. Domhoff, in Higher Circles, has shown that there is such an upper class, defined by such characteristics as income, schooling, marriage, social affiliations, clubs, and executive positions. Not all this upper class belong to the power elite; certainly not all the power elite come from this class. But those in the upper-most positions of decision making in American society are members of this class, whether through origins or co-optation. While the individuals in this class receive a lion's share of the income and control a vastly disproportionate amount of wealth, as Kolko has shown, the key question is not whether there is such a class of people, but rather who benefits from the decisions made by them and their representatives in business and government.

It is at this point that Kolko makes some trenchant comments on Mills' treatment of the upper class. For Kolko, the key element is not of class origins, but of currently active ties that lead to the operationalization of class interests. And it is clear, especially from the work of Kolko, Barnet, and Domhoff, that there are such currently operating ties. One such tie is the plethora of inter-locking directorships of corporations. Another, as Domhoff shows, is the memberships of members of the corporate elite in business associations and exclusive social clubs. Associations such as these lead to wide-spread current consensus on the outworkings of corporate interests.

It is necessary to emphasize that what is being outlined is not a conspiracy theory. The corporate elite operate on a shared set of assumptions. They do not control all decisions, even at the national level.

They do shape the discussion of the key issues, and control the key decisions. They exercise their power and influence more by setting the boundaries of discussion of the issues and problems that relate to the economy and society. These boundaries are always limited by the presently existing economic system, with its present distribution of wealth and power. There are significant differences of opinion within the corporate elite, giving the illusion of fundamental divisions within the business world. "Business conservatives," perhaps best represented by the National Association of Manufacturers, often hold positions seemingly diametrically opposed to those of the "sophisticated conservatives" of groups like the Committee for Economic Development. Whatever differences there are, they do not extend to the point of questioning the retention of the present "free enterprise" system. It is at times of crisis, such as the Great Depression, that this basic consensus is most clearly seen. While many business conservatives thought that the more liberal wing of the business elite had sold out to socialism with the New Deal, in fact the New Deal quite probably prevented a social revolution, and preserved the capitalist economic system for this society, with its inequitable distribution of income, wealth and power materially unaffected.

As a result of the increasing dominance of corporate power, it is more realistic to use the old-fashioned term "political economy" to describe society, rather than to speak of separate economic and political spheres. The upper reaches of government in America today are spheres of corporate dominance. Domhoff in Higher Circles, Kolko in Roots of American Foreign Policy, and Barnet in Roots of War show that the agencies that are primarily involved in foreign relations--the Departments of Defense, State, and the treasury, the National Security Council, and the CIA are by and large run by business executives and their bankers and lawyers imported for varying periods of time. These men (only one of 400 was a woman for the 27 years Barnet studied) in the top positions come into the agencies, make key decisions, shape the parameters of discussion of the issues--then move back into business circles. Robert McNamara, Johnson's brilliant Secretary of War is one of the prime examples--from Ford to the Defense Department, to the World Bank. Others move between industry, government, the universities, and foundations. This movement between government and industry that characterizes foreign relations is just as true in terms of shaping domestic policy, as Domhoff and others have shown. This is most clearly seen in the Federal regulatory agencies, which are business and industry regulating themselves. In both the case of foreign and domestic policy, certain key private elite associations are conduits of higher echelon managerial talent. In the foreign sphere, the channel is the Council on Foreign Relations. In the domestic arena, associations like the Committee for Economic Development are used, though none in the exclusive way the Council for Foreign Relations is.

It is this mobility between the private and the public sectors that gives business interests the predominant voice in shaping American political decisions at the highest level. Those in the top positions in government have not risen through civil service, as is characteristic of some other nations. Rather, top government is business.

Kolko and Domhoff have done the best work currently available on who makes up the power elite, and the channels through which they exercise their power. Richard Barnet has given a frightening picture of how one element of the power elite actually operate in his Roots of War. The first section of the book looks at the national security managers--their background, education, and operational values. Barnet's basic thesis is that one of the major roots of war is to be found in the structures and practices of American society. One of the structures most directly responsible for war and the permanent war economy is the national security bureaucracy. Many of the critics of the elitist theory of power as outlined in this article say that bureaucracy itself is the ultimate source of power, and because of bureaucratic inertia, top individuals cannot really shape the course of events. One of the keys to this understanding is the control over information and the expertise that reside at lower and middle levels of the bureaucratic hierarchy. One of the most disturbing things about Barnet's analysis is the way that information and expertise are almost irrelevant to the top national security managers. They operate on often preconceived notions of the world and people. The Pentagon Papers showed that at numerous points these bureaucrats worked on vastly mistaken assumptions about their adversaries. New facts channeled upward did little to change the way they saw the world and acted.

Selected comments from Barnet show the types of assumptions on which these bureaucrats operate. "As a group, the national security managers have been so removed emotionally from the human desperation that afflicts a majority of the world that they cannot understand why people will join a revolution... There is a process of natural selection through which leaders emerge with a certain social character that meets the requirements of the institutions through which they rise... The managerial class, even at its top echelons, are of necessity sober men who present a picture to the world of moderation, self-control, and probity... The two qualities these men prize in themselves and in others are loyalty and duty. Loyalty is the supreme bureaucratic virtue... But above all else, they are loyal to superiors because the bureaucratic ethic demands it. They know that their only capital is their marketability. To get power, they must prove acceptable to men who already have it" (pp. 59-62, passim). It is the combination of values and outlooks such as these, combined with the will for achievement that is so characteristic of these men, that leads to what Barnet terms bureaucratic homicide--the ordering of people killed half-way around the world while keeping one's own hands "clean."

What is blatantly obvious about the way these men exercise power in the name of national security is also in many ways characteristic of corporate bureaucracies. Those who get ahead and stay on top are the highly motivated achievers. They are the ones who keep things going, in more efficient and more profitable ways. Just as the national security manager would never question the morality of Vietnam, basic questions about economic justice will not be raised in the corporate setting, because such questions are outside the parameters of permissible discussion. Informing the power elite is a common set of assumptions about the goodness of the American way of life, the corporate way of doing things. As Barnet says, "American policy makers have assumed that anything that increases the capacity of the United States to control political and economic development around the world and to penetrate foreign markets contributes to the power of the United States and ultimately to the welfare of her people." (p. 67) This "American Business Creed," which Barnet lays out in his second section of Roots of War, always assumes that what is good for business is good for the people. That this is not so never enters the minds of most of the power elite.

The thesis of the first section of this article holds that there is a power elite that is responsible for the key national decisions. Other groupings that are usually understood as possessing great power, such as the Congress, organized labor, and big city administrations, do not affect the ultimate questions of war and peace, or the basic outlines and directions of the politico-economic system. On the bottom, the mass of citizens has almost no voice in these questions. Only a few observations about the middle and lower levels of the hierarchy of power will be presented here.

Two elements are missing in reality that are crucial to the theories of the sovereignty of the people. First, due to mass apathy, people are not coming together in voluntary forums to discuss significant issues and taking action through these forums. Secondly, there is the complete absence of effective connective organizations in the middle levels of power. As a result, instead of the will of the people penetrating upward, we are finding more of a mass society manipulated through such institutions as public education and the mass media. The mass of people are more acted upon than active. Their values are shaped by the institutions of society--the corporate media and education--far more so than the traditional sources of value like the family and church.

The sketch of the structure of power as presented in this article does not coincide with the view of reality that many are taught from grammar school through graduate courses in political science. This article is just a sketch, and the issues raised can be thoroughly explored in the works in the bibliography. For the basic outline of Mills' classical argument, the best brief account is his essay "The Structure of Power in American Society." This essay is most readily accessible in Irving Louis Horowitz, Power, Politics and People, pp. 23-38. This essay, written two years after The Power Elite was published, is a distillation of much of the book. Once a person grasps the basic outlines of the power elite thesis, perhaps the best place to go would be to Domhoff and Ballard's collection of critical essays. These were the original criticizers of Mills' book. They interact with his ideas from both radical and liberal perspectives. Other works in the bibliography criticize, refine, and strengthen the basic thesis of this article.

BIBLICAL MOTIFS

The picture of the structure of power presented here corresponds closely with two interrelated Biblical themes, both of which are foreign to modern ears. The idea of a structure of power fits very closely with the idea of the principalities and powers, demonic forces which lie behind the institutions and organizations visible in society. Many people would say that this is an antiquated, mythological way of looking at things. However, the Biblical writers and Jesus himself took the demonic element very seriously. What the concept suggests is that the structures of power in society do not in fact operate independently, but are influenced by powers beyond themselves. C.S. Lewis is one modern who took the work of the Satanic in the structures of society very seriously. Some of his perspective comes out in the preface to The Screwtape Letters:

The greatest evil is not now done in those sordid "dens of crime" that Dickens loved to paint. It is not done even in concentration camps and labour camps. In those we see its final result. But it is conceived and ordered (moved, seconded, carried, and minuted) in clean, carpeted, warmed, and well lighted offices, by quiet men with white collars and cut fingernails and smooth-shaven cheeks who do not need to raise their voice. Hence, naturally enough, my symbol for Hell is something like the bureaucracy of a police state or the offices of a thoroughly nasty business concern.

The second closely associated Biblical idea is that of Satan being the god of this present evil age. (See, for example, Ephesians 2:2, 6:12; 2 Corinthians 4:4; John 12:31, 14:30, 16:11) Again, the idea of a personally active Satan strikes moderns as ridiculous, but the Biblical witness takes a personal Satan very seriously. While some Christians have succumbed to a morbid curiosity about the demonic realm as it relates to possession and individuals, Satan's influence is today to be seen more in the shaping of the values of the present system, infusing society with a fundamentally anti-Christian worldview and mindset. It is this activity that creates a literally demonic element in the movement toward a mass society that has lost the ability to think for itself. Whatever one's initial reaction to this idea of the demonic in modern society, one cannot comprehend the meaning and effects of the structure of power in this or any other society without taking it very seriously. Dale Brown's article in this issue of the Post American should be read along with this one to get a better picture of the principalities and powers as they relate to the world of today.

SOME IMPLICATIONS

If the sketch of social reality presented here is correct, it has crucial consequences for Christians. The understanding of this reality is especially crucial today, given the resurgence of interest and concern in the social and political realm by evangelical Christians. If there is not a sound, integrated understanding of both the theological and the political-economic dimensions of the situations we face, action is likely to lead more to frustration than it is to fruitful change. Thus, work in the area of understanding is critical as the basis for sound action.

Many evangelicals are beginning to talk about the necessity of working in politics, because this is the arena, where people can effect change. The assumption on the part of some seems to be that if Christians get a piece of the action, they will be able to use political power to help bring about more justice in this society. There is a real danger of misunderstanding political reality in some of the ways this concern has been expressed. The sinfulness of humanity alone is not the only barrier to the hope for real change in society; the institutionalizing of sinfulness in a power structure that acts unilaterally without accountability is one of the clearest contemporary manifestations of the Fall. Real change in this society would necessitate a fundamental restructuring of the distribution of income, wealth, and the, means of power. It is clear that it is not in the interests of the governing class and power elite to allow this to happen. Because of the reality of the structure of power, mass organizations like Christian political parties and Evangelical Common Causes cannot be the starting point for meaningful Christian political activity. Even if such organizations were immediately successful in organizing people for action, they would at best belong to the middle levels of power, which provide no real connective between the lower levels and the power elite. Even if there were commonly agreed upon positions on issues by the Christian public (which is hardly the case!), political organizations at this time would provide no conduit for these values to reach and influence the top decision makers.

This is not to say that some day certain types of broadly based political organizations may not become useful and be able to operate with integrity; the mass base for them to influence decision-making does not yet exist among Christians. This is not to say that all political action and organization is useless. Significant change for large numbers of people can and has occurred. Action of limited scope can be taken on national issues; fruitful opportunities for meaningful change exist in most local situations. But the primary focus of the Christian community is not to become part of the power structure of this world. Its life, based on the values of the present and coming kingdom, is the primary witness to the world. The very presence of an obedient Christian church undercuts the present system with all its injustices. Many types of exploitation and oppression could not survive in their present forms if all who claim to be Christians were practicing disciples. The futility of a few activists claiming to speak for a morally impotent majority was shown by the activity of some of the clergy in the civil rights and anti-war movements of the 60s. The Church of Christ must first herself display those values it seeks to call the world to live by. Only an obedient church could serve as the base of political action with integrity. Meanwhile, consciousness raising must be a primary part of all Christian political activity. May we all be willing to make the costly sacrifices and changes in our lives that will be necessary for the church to play her role in society, until He comes.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barnet, Richard J. Roots of War Pelican, 1973

Christoffel, Tom, et al., eds. Up Against the American Myth, Holt, Rinehart, Winston. 1970

Domhoff, G. William The Higher Circles, Vintage, 1970

Domhoff and Ballard, Hoyt, B.C. Wright Mills and the Power Elite, Beacon, 1968

Heilbronner, Robert In The Name of Profits, Warner Paperback Library, 1973

Kolko, Gabriel The Roots of American Foreign Policy Beacon Press, 1969

Kolko, Wealth and Power in America Frederick A. Praeger, Inc. 1962

Mills, C. Wright The Power Elite Oxford, 1956

Mills. "The Structure of Power in American Society" in Horowitz, Irving Louis ed. Power Politics and People Oxford, 1963

Mintz, Morton & Cohen, Jerry S. America, Inc. Dell, 1971. Introduction by Ralph Nader

Newfield, Jack & Greenfield, Jeff A Populist Manifesto Paperback Library, 1972

Yoder, John Howard The Politics of Jesus, Eerdman's, 1972

Boyd Reese is a former staff member of Intervarsity Christian Fellowship and is an associate editor of the Post American.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!