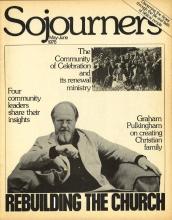

Graham Pulkingham was head of the Community of Celebration in Scotland, an international center for promoting church renewal, and had visited hundreds of churches renewing themselves as communities. He was interviewed by Wes Granberg-Michaelson, Bob Sabbath, and Jim Wallis at Sojourners in Washington, DC, in 1975.

Bob: What would you say to a group of people who are interested in establishing community?

Graham: I think the first thing I would do is ask them a question: "What do you mean by community?" Honestly, I've come to dislike the word "community" almost as much as I dislike the word "elder" because both of those terms have begun now to imply a kind of institutionalism. The connotations have become fixed. So many people talk about establishing a community or living in community, but probably no two people mean the same thing, even though both of them mean something very concrete and very specific.

Read the Full Article