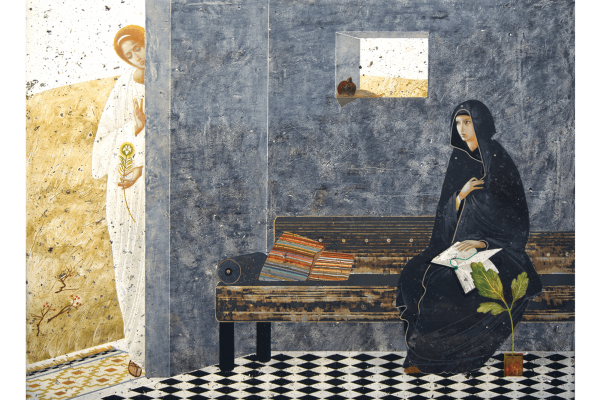

AT THE START of the war in Ukraine, images overwhelmed me. Families crowding onto trains. Teachers holding assault weapons. Nigerian students being held at the border. The clash of human tenderness with extraordinary aggression was arresting. In between checking updates from a friend—an art curator sheltering in Kyiv—Instagram suggested I follow Lviv-based contemporary icon artist Ivanka Demchuk. With fears of global annihilation humming in my head, Demchuk’s fresh, calming pieces, such as “Annunciation” and “Sophia the Wisdom of God,” captivated my attention and softened the edges of my growing despair.

In recent years, Lviv has become a hub of Christian sacred art technique and production. Lviv National Academy of Arts, from which Demchuk graduated, teaches icon creation, sacred space decoration, and icon theology. For centuries, icons helped make Christianity accessible to illiterate populations. But today, it strikes me that we need this life-giving artform in new ways. We are inundated with photographs of violence, from destruction in Ukraine to police brutality in our neighborhoods. Jesus Christ, our Wounded Healer, taught his disciples how to see injustice and move toward it. How can we, as Christian people committed to justice, cultivate these twinned capacities—seeing clearly and seeking social healing—within ourselves? We increasingly absorb information through visuals; it makes sense that the “medicine” would be visual too.

Visio divina (“divine seeing”) is a Christian contemplative practice that utilizes an image—such as a photo, painting, or icon—for prayer. By looking at the chosen image in silence, through a disciplined progression of four movements—seeing, meditation, prayer, and contemplation—we create space for God’s wisdom to emerge through our attention, thoughts, and emotions. As I practiced visio with Demchuk’s “Mother of Mercy,” my eyes were first drawn to the depiction of Christ in the Divine Mother’s center. When I widened my scope, I noticed the rough texture of the circle around her, which reminded me of a cell nucleus under a microscope or perhaps the Earth’s mantle. I thought of Julian of Norwich’s vision of a hazelnut in her palm, so small she thinks it might disappear, but it is, in fact, “all that is made.” Julian understands that it will not be obliterated, for it originates in and is sustained by the “love of God.” This was the message I needed in my fear and weariness: a reminder that we are shaped and sustained by the love of a relational God.

Many years ago, I worked as a transcriber for a literary project on the humanities and medicine. To teach better bedside manner and seeing the body as an integrated whole, a medical school incorporated art history into its curriculum. Through looking at paintings, some doctors-to-be learned compassion and the principle of interconnectedness. Likewise, the practice of visio divina renews our capacity to see, in the words of Ephesians, “with the eyes of your heart” (1:18). We remember that the fallen, human story is never the whole story. In seeking God’s wisdom through divine seeing, we soften our eyes and, therefore, our hearts, reaching them forward in hope, toward each other.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!