When the Reagan administration lost its final showdown vote on military aid to the contras, it blamed the U.S. churches.

I remember watching the entire debate in the House of Representatives on C-SPAN throughout what proved to be a very long day in February 1988. During the tedious but critical debate, my mind flashed back to the beginnings of the CIA-sponsored secret war that burst into the headlines with a Newsweek cover story in November 1982.

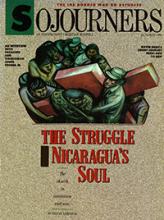

A week after that dramatic revelation, I was in Nicaragua on a previously scheduled fact-finding delegation of U.S. church leaders. We found in Nicaragua's revolution an embryonic and fragile experiment, full of both promise and contradictions.

I remember at the time fearing that the contra war could so easily overwhelm the early stages of rebuilding the nation, narrow the options, sap the resources, and harden the alternatives. I also remember fearing that this was precisely what Washington had in mind.

As the empty rhetoric on the House floor wore on, I recalled the role the U.S. churches had played through the years with some real gratitude and even a little pride. One year after my first trip, I was back in Nicaragua to help launch Witness for Peace with the first of many teams of North Americans in a nonviolent effort to stop the war. Witness for Peace volunteers became eyewitnesses to the contra war and to the human consequences of U.S. policy toward Nicaragua. In Nicaragua, Witness for Peace reported firsthand testimony and documentation on the war; and, back in the United States, several thousand returned volunteers were vital in convincing other church people and citizens that the war was wrong.

Read the Full Article