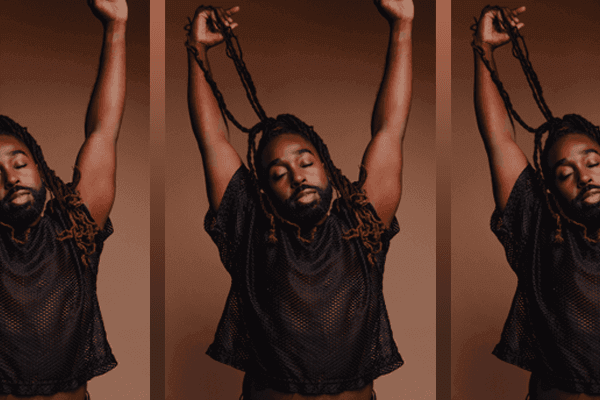

A MYKAL KILGORE performance isn’t just a show or concert; it’s an experience. Kilgore’s mind-blowing vocals and presence captivate, yes, but there’s more to it than that. In creating an atmosphere abundant in inclusion, empowerment, freedom, joy, truth, and love, Kilgore ministers to the soul. It’s a taste of the beloved community we hunger for.

A Black queer man, Kilgore uses his platform and prodigious talent to advocate for Black and LGBTQ issues. With a Grammy nomination in 2020 for his performance of the song “Let Me Go” further raising his profile, he’s getting even more opportunities to educate and entertain. In December, Kilgore spoke with writer and filmmaker Rebecca Riley via Zoom.

Rebecca Riley: When you perform, what do you hope audiences experience and take with them?

Mykal Kilgore: I want us to do a better job of being present with one another and seeing the thing inside each other that is eternal and sacred and perfect and special: I think that it is God. I want people to leave feeling like they have had a human experience at the show that allows them, and forces them, to be in their own emotions, to find pockets of empathy for others, and, more than anything else, to just truly see one another.

Read the Full Article