I MET JULIA ESQUIVEL for the first time in Mexico City, on a rainy afternoon more than 30 years ago, after my 2-year-old son, Abraham, and I crossed the exasperating metropolis by bus and clanky train. Flustered and dripping, I knocked on the door of her tidy home. Esquivel lived in exile, far from her beloved homeland, Guatemala. Henchmen in the service of Guatemala’s military rulers had pursued her relentlessly until at last she fled. I, a young, earnest Canadian, was traveling the northern continent, from Montreal to Costa Rica, preparing to write a book, recording the voices of women—such as Esquivel—scattered in this Guatemalan diaspora.

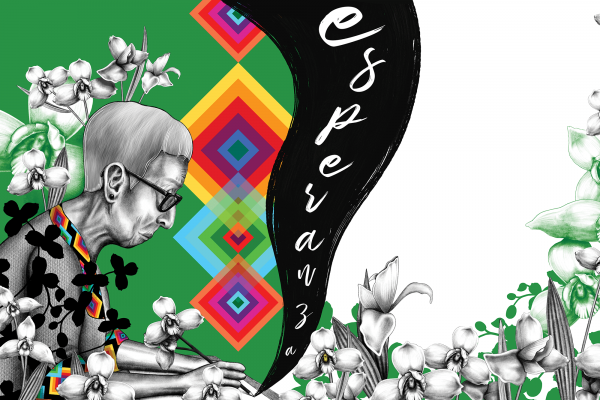

Esquivel was slender and small, silver hair framing her delicate, elegant face. She ushered us into her house, where we sat on cushions on the floor, drank hot tea, and read stories about St. Francis and a very bad wolf. We talked while Abraham toddled around, and we prayed. That was Esquivel: determined to pray through hurricanes, from the unimaginably large to the very small.

Our friendship spanned the decades. She was to become one of my greatest teachers. Because of Esquivel, who passed away last July, I—raised in a radically atheist household—am now a Christian. Esquivel first cracked open faith for me, showing my young rebellious self that the strongest power for transformation, for individuals as well as nations, came from a place of stubborn grace, a grace, like hers, that never surrendered.

The way a country treats its children

JULIA ESQUIVEL WAS born in 1930, in the western highlands of Guatemala, to a middle-class, progressive family. She was a surprise daughter to an older couple who had been told they would never have children. She grew up treasured. At 7, she said, she found herself before an image of Jesus on the cross; her heart broke with compassion for his suffering.

In 1947, Esquivel became a teacher, and several years later she traveled to Costa Rica to study theology. For a while, she tried on the idea of becoming a minister—first in the Presbyterian Church. She quickly found that the church refused to ordain women. From that time forward, she considered herself a Christian without a particular denomination; she called every imperfect church her home. She worshipped with Mennonites, Episcopalians, and Catholics.

Like people in any family, she quarreled with her siblings: other church members and, particularly, leaders. Young and filled with passion, she actually expected the widows and orphans to be cared for and the poor to be attended to with compassion. She believed this concrete truth: Jesus Christ made room for everyone at the table, starting with those who had been rejected by the world. Time and time again, she clashed with polite church institutions that did not embody what she believed were gospel values: inclusion, justice, the sharing of goods and gifts. Early in her young adulthood, Esquivel decided she would never marry, saying that even a good marriage would have stifled her.

For 12 years, Esquivel taught in a Protestant high school in Guatemala City. Then, in the 1960s, she began to visit the state-run Ciudad de Niños, a youth detention center. There, she told me, was where she had her second conversion.

“These young people brought me to the gospel. They questioned how far my faith in Jesus went. Was it a faith only concerned with personal salvation?”

This second conversion asked Esquivel tough questions about society and faith. “The way a country treats its children and adolescents is a measure of how humane or inhumane that society is,” she said categorically. These forgotten, abused children were signs of the state’s absolute failing. But the church had failed them too. She observed that churches—Protestant and Catholic—were stuck in a stale ecclesiology that favored the privileged. Those who had been born into wealth and power acted as if they owned the churches. Esquivel’s search for a faith in action expanded.

In the late 1960s, the Latin American Catholic Church was rocked by the afterquakes of the Second Vatican Council. Vatican II was a three-year gathering in Rome called by Pope John XXIII that radically changed the way the Catholic Church related to the world. The church invited its leadership—and all the faithful—to go out into the streets and countryside and engage deeply with the lives of real people, especially the poor. The Second General Conference of Latin American Bishops—a response to Vatican II that took place in Medellín, Colombia, in 1968—brought the church into an ever-deepening commitment to social change, from its leadership down to the grassroots. Liberation theology—an understanding of faith that puts the struggle of the poor and exploited at its center, sacrificing a soft religiosity that soothed the gilded faithful—was launched across Latin America.

In 1970, ever-ecumenical Esquivel founded a magazine, Dialogo, with an accompanying radio program. Both the magazine and the radio show addressed the commitment of societal transformation. The Dialogo team set off to record stories from the interior of Guatemala, where centuries-old structures of injustice ravaged the poor.

A time of trial

GUATEMALA IS UNIQUE in Latin America: The majority of its population consists of Indigenous people from 22 Mayan nations and one non-Mayan Indigenous group, the Xinca. The invading Spaniards of 1524 were after gold but, finding little, settled for agriculture, exploiting the Indigenous survivors of the conquest.

To this day, lands in Guatemala are among the most unevenly distributed in the continent. In El Quiche, the region where I lived for years, 70 percent of children are chronically malnourished. The most recent attempt to change this situation resulted in a protracted internal war—a 36-year nightmare—which ended, officially, in 1996. Government forces, rooting out a weak insurgency, slaughtered whole communities. Six hundred villages were destroyed. More than 200,000 people died or disappeared, and 1 million people—more than a tenth of the population—fled either into internal displacement or exile over the borders into Mexico and beyond.

The war ended, but the fierce injustices that provoked it were never resolved. Trauma sank deep into survivors’ lives, while the perpetrators became permanent power holders. Guatemala today is racked with terror linked to this past, visible now in relentless gang and drug violence, pushing catastrophic numbers of Guatemalans to flee north. Children die in detention at the U.S.-Mexico border, victims of this history of horror.

In the mid-1970s, as the wave of state violence peaked, Esquivel came under direct attack. The death squads were at her heels. At one point she fled her house, barefoot, in the middle of the night. She described it to me as a “prophetic” experience, a kind of holy reaction to horror: With death all around her, in her mind fantastic and shockingly real spiritual beings filled the air. She escaped down the dark highway to Guatemala’s Pacific coast and made her way to the house of Catholic priests in the town of Santa Lucia Cotzumalguapa.

After a short while, Esquivel set out on foot again. Two priests from Santa Lucia Cotzumalguapa were murdered shortly after. Esquivel managed to travel to the Tzutujil Maya community of Santiago Atitlan. There, she was received by compassionate elders who had known her in better times. They cared for her in prayer and fed her, bathed her, and sang to her. After she recovered, she returned to her small house, but friends insisted that the time had come for her to leave the country. She traveled to the ecumenical monastic community of Grandchamp in Switzerland, where she lived from 1980 to 1987.

The next phase was a time of trial. Away from her beloved people, but aware of the increasing genocide back home, Esquivel suffered the haunting guilt and loneliness of the survivor. “Why am I left alive?” she wondered. Many times, she told me, she would find her body bleeding its pain.

“I cried every day, going about my daily chores in the religious community,” she recalled. “I would wake up in the early hours of the morning and my nightgown would have spots of blood on it, because blood vessels in my skin were bursting from the tension of hearing these things and dreaming the rivers of blood. I could see, with the eyes of my heart, all the little towns like Pachay de las Lomas, Los Jometes, El Ixcan, all these little corners where I had been, and I could imagine the women in terror, the children turned into the soldiers’ football, the old people with their heads cut off. The genocide.”

A carrier of the Word

ESQUIVEL WAS TRANSFORMED. In stunned grief, and in the loudest way possible, she denounced the horrors going on in her homeland—and the direct connections between the violence in the Guatemalan highlands and the global U.S. Cold War strategy, which aimed to destroy social protest anywhere in the world believed to have a hint of communism.

Esquivel took up her pen. She wrote hundreds of poems and published four books, two of which came out in English: Threatened With Resurrection and The Certainty of Spring. With these publications and her outspoken presence at countless international gatherings, including the 1983 meeting of the World Council of Churches in Vancouver, British Columbia, Esquivel made herself heard. Standing in the center of the crucifixion of her people, she was able to declare that in the end, death would not win. Her words were a soothing balm to the survivors, a reminder that, in the midst of their ferocious suffering, they were not forgotten. And so she became not only a poet and a prophet, but also a comforting pastor holding out for her scattered people Christ’s unquenchable promise of life.

During fall 1998, about 10 years after Esquivel and I first met, I went to the Vancouver School of Theology to inquire about the priesthood. Esquivel visited Vancouver soon after, and we talked for days. She was delighted about my new path—and worried. Did I know what I was getting into? Could I really dream to be a carrier of the Word? Could I tame my impulsive heart, match humility with wisdom, and find a way to hold onto this light in a broken world? Despite all the contradictions, I tiptoed into the priesthood.

In 2009, ordained and with a few years of parish ministry behind me, I moved again to Guatemala, where I would live for the next four years at the ground zero of the genocide, in Santa Cruz del Quiche. I rented a house right across from what had been an army headquarters, a planning and launching spot for military sweeps as well as a torture center and prison. Often, overwhelmed with the sorrow, terror, and sheer suffering around me, I would jump on a chicken bus, barrel down the highway for a few hours, and leap off a block from Esquivel’s house. She had returned to Guatemala, to her own little sanctuary of books and modest, beautiful things, and there she prayed and wrote. I spent days at her house, sleeping in the tiny maid’s quarters. (Esquivel wouldn’t have a maid.) The holy days would pass, sometimes in silence, in thoughtful prayer, and sometimes with us laughing out loud, in love with the world.

The last time I saw Esquivel was at a gathering of religious friends not far from Guatemala City, on the site of a blockade up the road from a proposed open-pit mining site. We sat and leaned our heads toward one another. Later that afternoon, I celebrated Mass with some Catholic priests, on a makeshift platform built in the dust. Lifting the host, the bread of life, I glanced at my friend, my beloved teacher. She was sitting quietly, eyes closed. I have no doubt that she was listening to God.

Julia Esquivel died July 19, 2019, in Guatemala City.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!