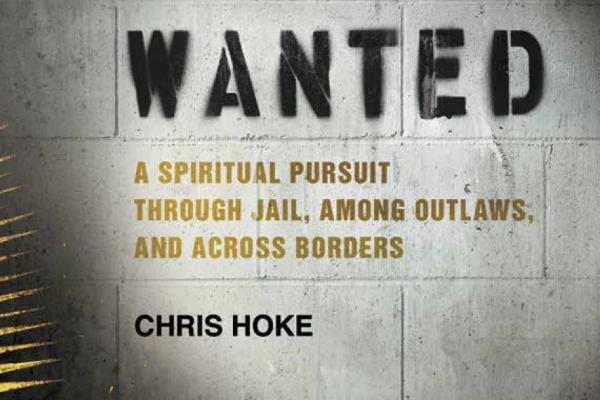

CHRIS HOKE’S Wanted isn’t a spiritual memoir in the sense of chronicling revelation over time, and while Hoke, as his own character, grows through the book, he isn’t tracking the movements of his own soul. Wanted recounts the moments in Hoke’s life as a pastor and friend to prisoners, migrant workers, and gang members when something else broke in. Whether or not it intends to, Wanted is a way of answering the question that plagues a lot of contemporary spiritual writing: What does spiritual mean, anyway? Outside the religious patterns we already know, how would we recognize it?

Hoke goes looking, and finds himself drawn to a jail in Washington’s Skagit Valley as an unofficial chaplain, leading Bible studies and hanging out with the men who soon request his visits. Many of them listen to the stories where Jesus dines with the people society rejected and ask if that could mean them too.

By hanging out in the margins of U.S. society, Wanted can’t avoid the question of how these men got there in the first place. It’s outside the purview of the book to fully take on the issue of mass incarceration in the United States, but in the stories there is ample evidence of ways in which our system is heartbreaking and often inhumane. To learn even the elementary details of these men’s lives is to see that nearly everyone has failed them. The alternative, a God who wants them, is Hoke’s theme, and part of his title’s double meaning. Such a God accompanies people to the ends of their shadows—to the fields where they hide from the police, into the houses they break into, to the horror of solitary confinement.

In taking on the difficult task of describing other people’s complex circumstances for his own literary purposes, Hoke is at his best when he lays bare his own stakes in this spiritual quest. When he makes it clear that he and his friends in prison are looking for the same answers, we get a sense for the spirituality Hoke wants us to find: one that doesn’t differentiate between the religiously decent and the forsaken.

It shouldn’t be a surprise that the most extreme human circumstances could lead someone to become open to transcendence. Whether it’s a prison cell or finding yourself alone in a foreign country without the right papers, when everything is stripped away, surrender to a greater power is surely an option people choose. What is surprising is that these (mostly) men manage to see outside their circumstances enough to love. This is what we call supernatural. Often it lasts. Donacio, a former gang member in Guatemala, leaves his established job as a prison chaplain to start his own grassroots ministry to others who’ve fled gangs, giving them jobs and skills, paying for these men’s need out of his own pocket. A man named Neaners, who had been in solitary confinement, tells Hoke, “I’m pretty sure I’m not the only one with a f***ed-up life, you know? I’m pretty sure there’s people who had it worse, and I want to help them.”

Those gestures of grace are among the most touching, because an unavoidable part of telling this kind of story is that the person writing it, and many people reading it, are not likely to find themselves shackled in handcuffs or on the edge of survival. We imagine, from a vantage point of relative comfort, that we could never endure such challenges, could hardly come out alive, let alone be generous. Maybe we wouldn’t—not all of Hoke’s stories include redemption. But we miss something big about Wanted—and more, we misunderstand the gospel—if we preclude the chance that love could appear beyond our own resources. It could chase us anywhere.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!