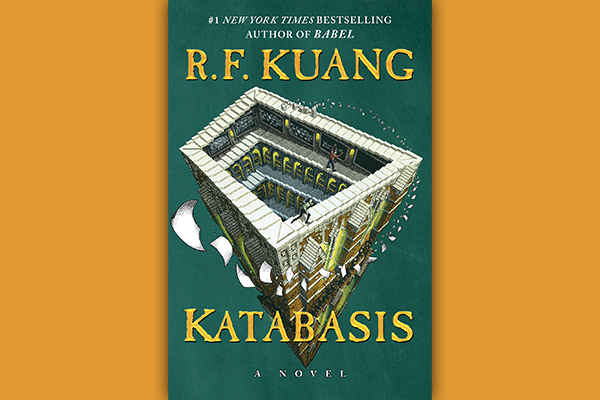

IN HER NEWEST novel, Katabasis, R. F. Kuang straps the mythic baggage of Dante and Orpheus onto two graduate students, Alice Law and Peter Murdoch. After accidentally killing their tyrannical professor, Grimes, the two sneak into hell to resurrect him. What they find there is barely distinguishable from their graduate studies. Kuang’s underworld is no cartoon inferno; it is a chilling landscape of extreme isolation, where the circles of punishment are the final expressions of the sins that isolate us in life.

The world of Katabasis (meaning “journey to the underworld”) is nearly identical to our own, save that magic is real. It has been institutionalized and is studied at the world’s premier universities. Grimes rules the Magick school at Cambridge with an iron fist, his abusive behavior excused as a function of his genius (and the price graduate students must pay for success). Alice and Peter are Grimes’ current star students, but this makes them more subject to his tyranny, not less. Alice “was of course underpaid and overworked, but this condition was common among graduate students and no one cared much about it,” Kuang writes. Neither Alice nor Peter (“the nicest guy in the world … who always holds you firm at arm’s length”) can see their suffering for what it is: a deluded isolation so complete that even hell seems preferable.

Read the Full Article