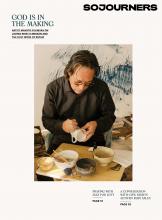

Artist Makoto Fujimura uses materials and techniques from nihonga, a Japanese style of painting. The pigments are pulverized minerals and precious metals applied in multiple layers, in what he describes as “a slow process that fights against efficiency.” Prayer and contemplation are woven into the work. The tiny mineral particles refract light, often creating subtle prismatic effects. It is a style of art made for the type of long, unforced gaze that slowly reveals evermore depth. Deceptively simple and quietly extravagant.

Fujimura’s thoughts on art, theology, and culture are, like his paintings, many-layered and refractive, celebrating God as love, beauty, and mercy while also contending with pain and desolation. He is a mystic as well as a painter, and in his latest book, Art and Faith: A Theology of Making, he speaks out of his spiritual and his artistic practice.

But Fujimura also builds on three decades of reaching far outside his studio to evangelize on the necessity of art for human thriving and the call to shift from fighting over culture to caring for and nurturing it. He founded the International Arts Movement in 1992, which facilitates connections and communication between groups seeking to creatively and positively impact the culture, whether they are from the arts, music, business, education, or social change organizations.

Read the Full Article