TO THE LEFT of a buffalo photograph on my wall, a rosary hangs from a thumbtack. Frequently, my eyes linger there. It came to me a couple of years ago on my birthday as part of a gift from my mother — looped through the ribbon of a wrapped box that contained a tea set. When I held the rosary before my face, I found it curious. My mother explained that it had been my late father’s, and that it was one of his most prized possessions. I was a little stunned because I had never seen it before. It was a gift, my mom continued, made by his grandmother who died two years before I was born. Now, it had come to me.

My great-grandmother’s parents were part of a group of 25 Red River Métis families who settled on Spring Creek in central Montana in 1879, an area now known as Lewistown. They, like all the tribes of the region, were pursuing the final dwindling herds of buffalo. It was a tumultuous time to be Indigenous, with settlers flooding the landscape from all points east and gobbling up land, whether it had been promised to Indians or not.

The origins of my Métis people can be found in the late 1600s, and likely earlier, when the first European traders first began establishing trading posts in the Red River Valley. This region, named for the mighty Red River of the North, is centered at what is now Winnipeg, Manitoba, and extends into today’s Minnesota and North Dakota. These early Europeans, mostly from France — with some coming from Scotland, Wales, and England — married into the Indigenous people already inhabiting the region: Cree people and Ojibwe people. From these unions sprang descendants who created their own unique, mixed-culture people — the Métis.

The border crossed us

WE MÉTIS ARE a distinct cultural and Indigenous people recognized as such in Canada but not in the United States. The difference between me and my Canadian relatives? Our respective addresses relative to the 49th parallel north on this continent, otherwise known as the border that separates the U.S. from Canada — the Medicine Line. We are the same people; we didn’t cross the border, the border crossed us.

From the early 1800s until the buffalo nearly went extinct in the 1880s, the people from the Red River ventured out onto the plains in convoys of two-wheeled Red River carts — a Métis invention largely considered to be the first use of the wheel on the Northern Plains — to hunt buffalo. These enterprises contained anywhere from a few dozen carts to more than 1,000, essentially moving entire towns’ worth of people out to practice their traditional economy. It wasn’t just subsistence hunting, it was trading: buffalo hides and, most importantly, pemmican — a food product made of dried meat, fat, and usually some kind of berry (like the high cranberry, or pembina, from which the Pembina Band of Chippewa Indians earned their name) that was highly valued not just for its caloric wallop but also its accompanying portability.

Beginning around 1820, these ventures out onto the plains often included a Catholic priest; priests had begun arriving just a few years before. It was an uneasy alliance at first. The Métis had developed their own unique blend of Catholicism before the priests came, taking the lay teachings of the first-arriving Europeans and blending them with Anishinaabe cosmology to create what Canadian scholar Dr. Émilie Pigeon called a “lived” Catholicism. It wasn’t a conversion to Christianity; it was an inclusion. Life was hard in the region, and Indigenous people were happy to take whatever spiritual power they could. Spirituality and prayer were as much a part of life as breathing. There was no reason not to include these new ideas with what they already had.

This began to change when missionaries arrived in the Red River Settlement from the other side of the Great Lakes region. The missionaries didn’t like the way the Indigenous worshipers played fast and loose with church doctrine. They didn’t like that there were couples calling themselves married who had done so outside the auspices of the church — and with heathen children the result of these unions. But the problem was, they didn’t initially have the strength to enforce any change to the Indigenous way of doing things. Then, as more settlers arrived — to the dismay of the people already living there — and built schools, and began to establish and enforce rules, the balance of power shifted. A couple of decades preaching out on the prairie during the buffalo hunts, and the spiritual lives of a growing number of Métis people began to reflect a more European practice of Catholicism.

Exploring the mystery

GROWING UP, MY family was not a religious one. I don’t recall my father ever attending church, though now, with the revelation of his prized rosary, I wonder about my own Catholic baptism. I always assumed it was to please my grandparents, though they never exerted any kind of spiritual pressure on my family that I am aware of. Now I wonder if it was something my dad saw as important. My mom, who today remains a spiritual person but would never claim to be religious, was not raised Catholic. Instead, she was in and out of various churches, mostly Lutheran, during my adolescence. I too attended off and on for a couple of years during my elementary-age years, both with her and as a guest of another family whose daughter was a friend of mine. Even so, I would be surprised if I attended more than a score of services, or even a dozen, and to this day I wonder why I ever did.

As an adult, I’ve dabbled in other spiritual traditions. Most recently, I have spent more than a little time reading Buddhist writers and contemplating Zen. As relevant as many of the ideas I have encountered are to my animist, nature-based, tree-hugging-dirt-worshiping proclivities, it hasn’t seemed quite right for me. So much still feels dogmatic and hierarchical, even misogynistic. As I struggled with the language — the names, the lineages, the terminology — I also wondered what use it was to learn the tongue of another faith when I did not even know mine?

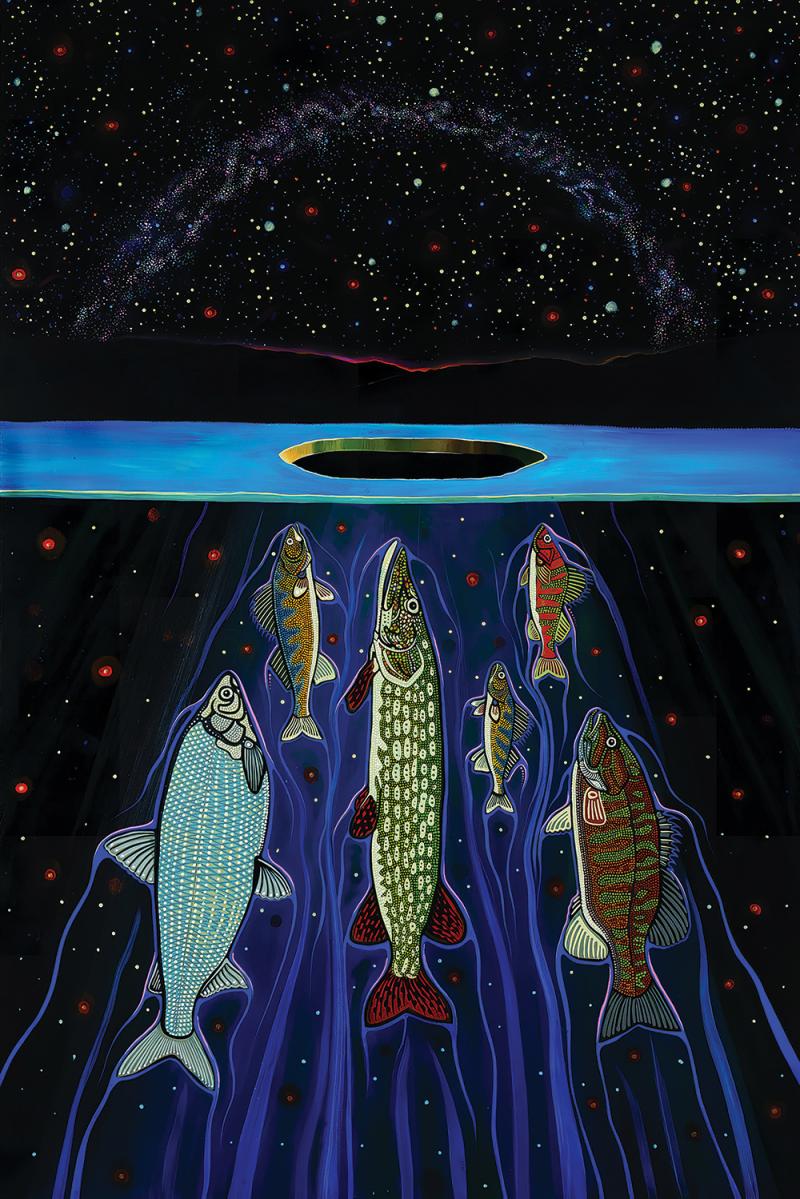

inlineimage_latray.jpg

I became curious about Catholicism because of a decade of research into the history of my Métis people, and the blend of European faith with that of the Anishinaabe. It was a hint of the “lived” Catholicism of my Métis ancestors that I hoped to find on Christmas Eve when I decided to see if my local church in Frenchtown, Mont., would be holding a midnight Mass. This was as good a chance for Catholicism to welcome me back into the fold as it would ever get. I was interested in exploring the mystery, to see if this particular brand of spirit would reveal any fresh insights into the spiritual lives of my ancestors. Also, if I had a community church, St. John the Baptist was the closest thing to it, even sharing the building with the Lutheran congregation of my youth until the Lutherans built their own small church not far from where the valley’s first Catholic church was constructed of hewn logs to serve the Red River Métis worshipers. My high school choir performed Handel’s Messiah from the balcony there one afternoon in the early ’80s. I’m fairly certain that was the last time I ever set foot inside it.

I found the church website and scanned for a midnight Mass on the schedule. There wasn’t one listed. I started clicking around. At that point, I wasn’t looking for anything in particular but immediately was struck by what I didn’t find. There was nothing mentioned about Indigenous boarding schools. It had only been a few months since the remains of thousands of children had been found in unmarked graves in Canada and the U.S., a heartbreaking story the Catholic Church played a huge role in. And while there was an 800 number on the website to call if you “know of or have cause to suspect an incident of child abuse or neglect,” there was nothing related to conciliatory remarks about the church’s own sad history of abuse.

Returning to the church’s website a few days after the Supreme Court cast aside the half-century-old Roe v. Wade decision, I find links to celebratory posts in favor of this cruel decision. I find links to websites for “ex-gays” that amount to little more than “pray the gay away” propaganda. I find these attitudes hateful. I am reminded how I felt on Christmas Eve, like a man standing in the doorway of a church my ancestors had found some peace in during very troubled times, only to find the door slammed in my face.

I won’t cast my shadow there again.

Hard to reconcile

THE PALE, LINGERING twilight of early summer is settling outside the window of my home office. My eyes linger on the view of the western horizon, then drift back to the wall just above my computer monitor. An old black-and-white 8x10 photograph hangs there in a cheap, black plastic frame. The image is of a small herd of mashkode-bizhikiwag — Ojibwe for “buffalo” — spread across a grassy plain. In the shadowy light, they are little more than dark spots against a gray landscape. There is nothing special about the photograph, but I stare at it often. It brings me peace of mind.

Beyond the status as the U.S. national mammal, bizhiki is a sacred animal to many people of North America, including mine. In the tradition of the Seven Grandfathers’ Teachings of my Anishinaabe people , bizhiki represents mnaadendimowin, or respect: Respect for the self, for others, for all life. Bizhiki can be said to be a representative of what so many of us might better understand as the Golden Rule: Treat others as you would want to be treated.

These seven teachings of the ancestral grandfathers — humility, bravery, honesty, wisdom, truth, respect, and love — provide all the guidance I need to live an Anishinaabe life. On my best days, I hope “every footstep becomes a prayer” as the life is described by the late Ojibwe elder Edward Benton-Banai. But like so many people who strive to live a spiritual life, I am not always living one of my “best” days. It is only recently that I have even dedicated myself fully to trying to live an Anishinaabe life. Along the way, my feet have grown dusty and dry in making footsteps to this spiritual place. They are ready to linger awhile.

It is hard to reconcile the world I live in today with the decisions my ancestors were forced into. They chose to incorporate elements of Catholicism into their daily lives for some reason that I can’t uncover. I know too much now about how the long game played out, and I struggle with my encounters with Indigenous Christians because it feels like the ultimate betrayal. That is a struggle I will face for the rest of my life, I think. It is a lonely undertaking too, because where I live isn’t exactly an Anishinaabe stronghold. To immerse myself in that spiritual life, I will likely have to relocate to the other side of the Medicine Line, to Manitoba, or perhaps Saskatchewan.

But I have buffalo, my magnificent mashkode-bizhikiwag, near me. I can be in their presence in minutes. They are living, breathing reminders of a different kind of spirit that my people pursued for centuries. Among them, at a safe distance, I find some solace.

They are not extinct. Neither are we.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!