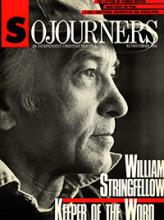

For the past quarter century, America's most important theologian has scarcely even been recognized as such. He has been largely ignored by academic theologians and, when recognized at all, introduced by the sobriquet, "William Stringfellow, the noted lay theologian," meaning by that not simply non-ordained, but amateur, untrained, uncredentialed, and illegitimate. It took Karl Barth to recognize his power as a man to whom America should listen.

Because he wrote for an audience of his peers—and he regarded everyone as his peer—Stringfellow's books were not laden with footnotes, jargon, dense and convoluted arguments, or discussions about other authors. Hence to many he did not appear to be doing serious theology, but rather a kind of "popularization." But a popularization of whom? There was no one like him that he might simplify.

His tone was acerbic, each word minted in fire and annealed in inexpressible physical suffering. The hammer blows of his prophetic message landed with such force that many overlooked the carefully nuanced subtlety of his argument. Stringfellow's mind was full of surprises, like the clowns he so admired.

The freedom of the Word of God in which he was established meant that he was capable of infinite malleability within the fidelity of his ethical concerns. Not that he blew with every wind; quite the contrary. I mean simply that the moment I thought I had him pegged, the moment I felt he had painted himself into a corner or had skewered himself upon a contradiction, I discovered him to be somewhere else altogether, celebrating the liberating freedom of the Word of God.

His own contemporaries scarcely sensed the full measure of this authentic prophet while he was among us. I will make this prediction: A decade hence Stringfellow will have become the subject of numberless dissertations, theses, term papers, scholarly convocations, and learned articles.

Read the Full Article