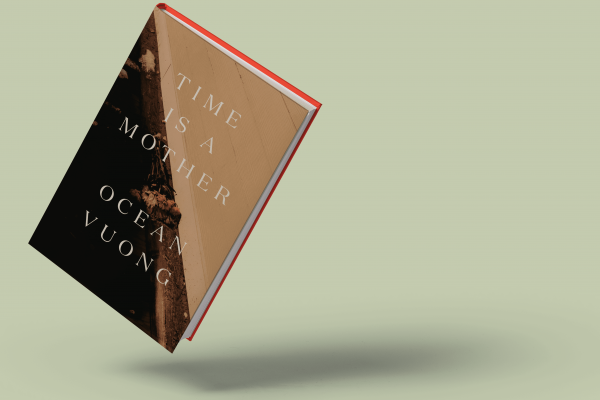

IN OCEAN VUONG'S latest collection Time Is a Mother, the T.S. Eliot Prize-winning poet reaches for depths of what was lost.

We encounter Vuong submerged in profound and compounding grief after the death of his mother. The book’s epigraph from César Vallejo reads, “Forgive me, Lord: I’ve died so little,” touching on the guilt that can accompany those left behind after a death. These poems hold the tension between looking back and moving forward, with the awareness of someone acquainted with feelings “that made death so large it was indistinguishable / from air,” as Vuong writes in “Not Even.” Those grieving search for comfort, while also examining life before loss—sometimes recognizing that grief was always present.

Time Is a Mother is full of questions that reckon with these past experiences. One of the first poems asks, “How else do we return to ourselves but to fold / The page so it points to the good part.” Other verses ask, “What if it wasn’t the crash that made us, but the debris?” and “How come the past tense is always longer?”

Read the Full Article