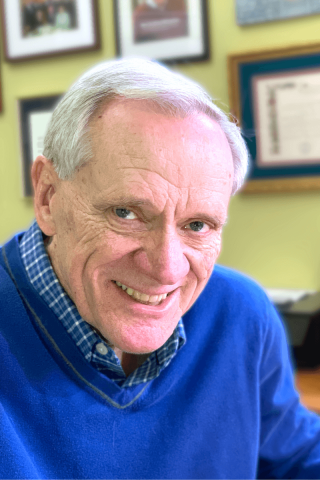

Wes Granberg-Michaelson is a contributing editor to Sojourners. His forthcoming book is The Soulwork of Justice: Four Movements of Contemplative Action (Orbis Books).

His other books includeing Without Oars: Casting Off into a Life of Pilgrimage, From Times Square to Timbuktu: The Post-Christian West Meets the Non-Western Church, and Future Faith: Ten Challenges for Reshaping Christianity in the 21st Century.

He served as general secretary of the Reformed Church in America for 17 years from 1994 to 2011. Previously he held the position of director of church and society at the World Council of Churches in Geneva. Earlier in his career he served as executive and legislative assistant to U.S. Senator Mark O. Hatfield (1968-1976) and then as the associate editor of Sojourners magazine when it was founded. He played a leading role in establishing Christian Churches Together in the USA, and presently helps guide the development of the Global Christian Forum. Over the course of his ministry his ecumenical work has taken him to all corners of the world. In addition to the recent titles listed above, he is the author of Underexpected Destinations: An Evangelical Pilgrimage to World Christianity and Leadership from Inside Out: Spirituality and Organizational Change, as well as four other earlier books. His numerous magazine articles have appeared in Sojourners, The Christian Century, The Church Herald, Ecumenical Review, and other publications.

In the fall of 2012, Granberg-Michaelson was appointed as a Distinguished Visiting Scholar at the John W. Kluge Center of the Library of Congress. While there he researched and wrote the book From Times Square to Timbuktu: The Post-Christian West Meets the Non-Western Church (Eerdmans, Fall 2013). The book deals with the effects of the shift in world Christianity to the global South, and impact of global migration on congregational life and society in the global North. It was chosen to be part of the 2013 National Book Festival in Washington, D. C.

Granberg-Michaelson is a graduate of Hope College and Western Theological Seminary, both in Holland, Michigan, and was ordained as a Minister of Word and Sacrament in the Reformed Church in America in 1984. Presently he continues his work in ecumenical organizations, in writing and public speaking on issues facing world Christianity, and consulting to church-related organizations. He serves today on the governing boards of Church Innovations and the Global Christian Forum. His wife, Kaarin Granberg-Michaelson, is an ordained minister in the Reformed Church in America, and they have two children. He and Kaarin live in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Posts By This Author

Engaging in 'Wider Ecumenism' to Cure Injustice

From the Pacific islands, Rev. Male’ma Puloka shared how only 0.03 percent of the world’s greenhouse gases are produced by the islands in her region, but they are they ones directly experiencing the devastating effects of climate change. What more can be done by the churches to combat global warming and defend the integrity of God’s creation?

We also began looking at global economic inequality. The facts are these: the top 20 percent of the world’s people control 83 percent of the world’s wealth. The next 20 percent control 11 percent of global wealth. That leaves the bottom 60 percent of the world’s population with only 6 percent of the world’s economic wealth. What can the churches do in the face of such severe global injustice?

Beneath this some voiced the cry for hope. Facing such stark challenges of injustice requires a foundation of spirituality and prayer that can inspire our Christian witness.

The Global Pilgrimage of Christianity

Like most Asian nations, Korea experienced the influx of Western missionaries in the late 19th and 20th centuries. In Korea they are revered today by Christians. But in asking why the church grew here in ways unique on the Asia continent, it’s fair to say that the witness of faith which stood against oppression, and in solidarity with the poor and marginalized, accounted at least in part for this difference.

Today, however, the churches in Korea face the difficulties of being part of the society’s economic prosperity and success. The stories of congregations like Myungsong and Yoido are utterly remarkable and inspiring. Yet as a whole, Christianity in this society is no longer growing as before. Korean Christian friends tell me that it has “plateaued.” And a major worry, echoing that of the church in the U.S., is the growing disaffiliation of young people.

Addressing the Changing Face of Faith

The 6.5 million people in the greater Houston area now surpass New York City and Los Angeles as the most racially and ethnically diverse urban area in the U.S. That's the site where a broad spectrum of U.S. church leaders met this week to consider the impact of immigration on their congregations, and on the rapidly changing expressions of Christianity within North American culture.

The group gathered at the annual convocation of Christian Churches Together in the USA, which includes the leadership of the U.S. Catholic Conference of Bishops, several Pentecostal and evangelical denominations, the Orthodox Churches, some Historic Black churches, and nearly all the major historic Protestant denominations. All of these are experiencing the impact of immigration. Most dramatically, for instance, 54 percent of millennials — those born after 1982 — who are Catholic are Latinos. Of the 44 million people living in the United States who were born in another country, 74 percent are Christian, while only 5 percent are Muslim, 4 percent Buddhist, and 3 percent Hindu.

While church leaders in the U.S. have expressed united support for the reform of U.S. immigration laws, this is the first time an ecumenical body has gathered to examine together the actual consequences of immigration on the life and witness of its churches.

Christian Leaders Should Prepare for the Long Term

Wesley Granberg-Michaelson’s advice to Christian leaders: Discern God’s call and learn how to sustain your inward life for the long term.

“Leaders have to know who they are,” he said.

“When everything else crumbles and when you are in situations of disillusionment, when plans haven’t worked out, when colleagues have disappointed you, there’ll come those times when you say, ‘Why am I doing this?’

“At that point, what is needed is a deep and abiding sense of God’s call.”

Granberg-Michaelson’s call led him to take on a variety of roles in his career. He served from 1994 to 2010 as general secretary of the Reformed Church in America. He is the author of several books, including “Leadership from Inside Out: Spirituality and Organizational Change.”

Before that, he served as research assistant for U.S. Sen. Mark Hatfield, managing editor of Sojourners magazine, co-founder of a nonprofit organization, and director of church and society for the World Council of Churches.

Q: You’ve had a really interesting career, including working on Capitol Hill and in Geneva, Switzerland with the World Council of Churches. What did you learn from those roles?

Working in the U.S. Senate with Mark Hatfield is when I first learned about how important it was to have a group that had a deep level of trust together. And that you have to work on building that.

And then in the life of Mark Hatfield as a U.S. senator, I saw the importance of giving voice to crucial issues in ways that helped empower others. The role of prophetic ministry I really witnessed in his life in the U.S. Senate, the kinds of stances that he took against the Vietnam War, stances that were rooted in his own convictions.

Those were qualities that came out of his Christian character. But those were also qualities I saw and learned in that secular context.

When I went to Geneva with the World Council, I got to see the enormous complexities of how organizations function and how decisions are made. I was very involved in a restructuring effort.

We spent a lot of time figuring out models for how church bodies can govern themselves. And the World Council was in a deep discussion — conflict, really — with its Orthodox members at that point. I was involved in a special commission on relations with the Orthodox.

One of the key issues was how we make decisions. To the Orthodox mind, it was incomprehensible that a central committee of 150 people could meet together and by a majority vote determine God’s will.

That led to a whole fascinating journey that I’ve continued on ever since, to rethink how church bodies make decisions.

Out of that dialogue came an embracing of models of consensus decision making, which the World Council still uses today, where 150 people will come to a decision that they arrive at by consensus. It’s a discussion, a deliberation that’s led very carefully, very artfully, taking into account the opposing points of view and getting to a point where either the body as a whole agrees or a minority that may not agree are willing to say, “We will step aside and allow this to go forward.” Or convictions are held so strongly that the body as a whole decides it’s really not ready to decide this.

None of these functions by majority vote. It’s a very different model, and I think one that’s much more attuned to how the church could make decisions.

Why I’m More Worried About Ebola Than ISIS

The headlines and talk shows are dominated by the response ISIS. To be clear, this group readily uses fanatical and brutal actions to achieve its radically exclusive vision. The images they skillfully project are like violent, X-rated video games made real. No wonder that many react to this horror with chills going down their spines. But there is something that worries me more: the ongoing Ebola crisis.

How did ISIS come about? Sure, there’s huge complexity. Yet, we know that ISIS never would have emerged without, first of all, the U.S. invasion of Iraq and the ensuing, devastating war that left that nation in physical, political, and psychological shambles. Second, the sectarian, Shia-dominated regime, which emerged as the final U.S. ground troops left, further radicalized Sunni extremists. These factors were the breeding grounds for black-clothed fanatics ready to cut down any who differ with their identity, even if the majority of its victims are Muslims.

ISIS’s greatest recruiting tool is continued and renewed U.S. and Western military intervention in the Middle East. That, of course, is what their brutal actions are attempting to provoke. The moral callousness of this strategy inspires the fear which they desire and welcome.

However, ISIS can and will be contained. The neighboring regimes in the region are all deeply threatened by ISIS. In the end, they will be compelled to combat and resist ISIS the more these fanatics move out of the desert and toward others’ homelands. It will be bloody, but eventually other nation states and threatened sectarian groups, representing for the most part more mainstream and globally dominant expressions of Islam, will contain and defeat ISIS. The necessity and means of outside military assistance from the West and elsewhere is highly debatable, and at the end of the day, I don’t believe this will be the decisive factor.

Money Talks: World Council of Churches Disinvests in Fossil Fuels

The Supreme Court’s Citizen’s United case infamously affirmed money spent in political campaigns as a form of free speech, thus declaring various legal limitations unconstitutional. The ruling gives a political megaphone to those with the most money and has been decried by many as contributing further to the nation’s political dysfunction and rigid polarization. I strongly agree.

But this ruling came to mind again when I heard the news that the World Council of Churches, at its Central Committee meeting in early July, had made a decision not to invest in fossil fuel industries. In fact, money does talk. Where institutions place their invested funds is not a neutral, pragmatic matter. It speaks volumes.

Burying the Hatchet (Almost Literally)

The quaint Pillar Church sits directly across the street from Hope College in Holland, Mich. — the first congregation established by a wave of Dutch immigrants to the area. When I enrolled at Hope in 1963, all I knew was that virtually no students went to Pillar Church.

A half century later, the story of Pillar Church tells a much larger narrative of the long and arduous journey toward authentic Christian unity.

Pillar Church and Hope College were both founded as part of the Reformed Church in America, a denomination formed by Dutch settlers to New Amsterdam (we now call it New York City) in 1628. A later wave of Dutch immigrants settled in the Midwest, particularly western Michigan. Some of them broke away and established the Christian Reformed Church in North America in 1857.

From its founding, Pillar Church had been a member of the RCA. But in 1882, a group siding with the emerging CRC seized the church building, locked its doors with chains, and, grasping axe handles, defended it against their fellow congregants. From then on, Pillar Church was a CRC congregation, and it became essentially foreign territory to those of us at the RCA-affiliated school across the street.

One would think that sharply defined theological differences among Reformed Protestants — who are famous for their theological exactitude — would have been the cause of such a dramatic intra-ethnic split. But no.

Remembering Tiananmen

We’re commemorating the 25th Anniversary of the massacre at Tiananmen Square this week. The question is whether anyone remembers. China’s rulers have worked hard for the past 25 years to wipe this memory card clean.

It began when they wiped up the blood on Tiananmen Square, after turning their armed forces against their own people — students and supporters who were seeking more openness and reforms in their system. And this attack on memory has continued relentlessly, to this day. China’s censors are so thorough that even the words “May the 35,” as a veiled reference to those fateful events on June 3-4, 1989, are quickly removed from any appearance on social media.

China’s rulers have good reason to repress these memories. While attention has been focused on what happened in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, few recognize that the demonstrations and movement for reform, initiated by students in Beijing who considered themselves patriots, spread around the country. Shen Tong, a 20-year old biology student in Beijing at the time and a leader who narrowly evaded police to leave the country after the crackdown, told NPR that eventually as many as 150 million people in cities throughout the country were on the streets.

Louisa Lim’s aptly titled book, The People’s Republic of Amnesia: Tiananmen Revisited, recounts not only the stories of those involved in the brutal crackdown at Tiananmen, but also documents the bloody suppression which took place at Chengdu. Recently, as NPR’s Beijing correspondent, she took the famous picture from this time of “Tank Man” — a lone student standing in front of Chinese tanks — to contemporary university students in Beijing, asking if they could identify the iconic photo. Of 100 students, only 15 knew what it was, and they didn’t wish to discuss it. Their names were withheld out of respect for their anxiety.

Who Will Take Personal Responsibility for Denying Climate Change?

This week the National Climate Assessment Report was released, documenting the disruptions already being experienced due to global warming. President Obama has tried to raise the alarm by talking about the Report with weather reporters in different cities.

What’s amazing to me are not the findings of the report. More flooding, extreme temperatures, drought, severe wildfires — these have been predicted for years. And the crushing effects of global warming around the world are felt most by the poor and marginalized.

Argument Over Pope Francis' 'Inequality' Tweet Misses the Point

The latest dust-up about the unscripted words of Pope Francis came this week when he tweeted, in Latin, “Inequality is the root of social evil.” Conservative Catholics had their underwear in a bundle, nervously tweeting away about the dangers of addressing complex issues on Twitter, and warning about thinking that “redistribution” would solve global inequities. Some feared this was giving Thomas Piketty’s new popular book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, more press. Liberal Catholics were delightfully surprised, once again, and argued that the pope was doing nothing more than putting Catholic social teaching into a tweet.

Inequality is the root of social evil.

— Pope Francis (@Pontifex) April 28, 2014But this latest interchange, happening of course between Catholics in the global “North,” misses the real point.

What If U.S. Christianity Needs More Immigrants?

Evangelicals around the country are praying for Congress to bring fair and just immigration reform to a vote. Often, advocates within the Christian community voice concern for the “least of these” — the unauthorized immigrants who are living in the shadows. But churches shouldn’t view Congress’ critical immigration decision as simply a matter of compassion for the “other;” immigration might be the lifeline that American Christianity needs.

Much has been written about the way that growing numbers of “millennials” are walking away from the church. The music, programming, and even vocabulary of many Christian churches seems aimed at solving the puzzle of how to keep young people interested in faith and keep them sitting in the pews. Yet while it seems millennials are walking out the front door of U.S. congregations, another group is knocking at the back door: immigrant Christians.

The Hidden Immigration Impact on American Churches

As Congress makes a final attempt this fall to act on comprehensive immigration reform, the debate is focusing on “securing” our borders and offering a path to citizenship to the 11 million residents here without proper documentation. These politicized arguments, however, don’t see the forest for the trees.

We’re not viewing the broader impact that immigration has had on American society, especially since the last major immigration reform of the 1960s. In particular, we’re missing the way immigration is transforming the religious life of North America.

We commonly view immigration as introducing large numbers of non-Christian religions into U.S. society. True, because of immigration in the last half century, America has become the most religiously diverse country in the world, with thousands of mosques and temples dotting our religious landscape.

'Break My Heart With What Breaks Yours'

High-octane contemporary worship with smoke, flashing lights, and words on huge screens energize and empower 3,400 Pentecostals from 69 countries filling the Calvary Convention Centre in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia,. This is the 23rd Pentecostal World Conference, a triennial gathering of pastors, leaders, and youth from around the globe. I’m here as part of a delegation from the Global Christian Forum, warmly invited, seated right in the front, and including representatives from the Lutheran, Orthodox, Seventh-Day Adventist, Mennonite, African-Instituted and Reformed church bodies, all members of the GCF steering committee. We’re easy to pick out of the crowd, since we’re the only ones who don’t spontaneously raise our hands in worship. I hope that image doesn’t make it to the big screens.

The explosive growth of Pentecostalism is an astonishing chapter in the story of world Christianity’s modern history. In 1970, Pentecostals (including charismatics in non-Pentecostal denominations) totaled about 62 million, or 5 percent of the total Christian population. In the four decades since, Pentecostals have grown at 4 times the rate of overall Christianity, and 4 times faster than the world’s population growth. Today they number about 600 million — one out of every four Christians in the world, and one out of every 12 people alive today. Most of this growth has come in the global South, in places like Africa, South America, and — yes — Malaysia.

The Pentecostal World Conference doesn’t look much like a typical denominational or ecumenical assembly. It’s more like a global revival service. Several of the world’s best-known Pentecostal preachers and leaders deliver stirring messages, complete with altar calls for those seeking the fresh empowerment of God’s Spirit in their lives and ministries. It’s a far cry from a Reformed Church in America General Synod, which I facilitated for many years. But these keynote speakers, along with the workshops held each day of the conference, open a window into global Pentecostalism’s present trends, challenges, and directions.

In writing From Times Square to Timbuktu: The Post-Christian West Meets the Non-Western Church, I found that one of the most intriguing questions I encountered is how rapidly growing forms of Christianity in the global South deal with social and economic issues within their societies. So in Kuala Lumpur, I was especially attentive to what might be said by the world’s Pentecostal leadership about the biblical call to justice and mercy. And I heard a lot that I wish I could now go back and add to my book.

Radical Welcome

As demographics shift and migration brings global Christianity to the church down the street, how will U.S. congregations respond?

ONE OF THE most well-known and revered icons today is Andrei Rublev’s reflection on the Holy Trinity, painted between 1422 and 1425 in Russia. It depicts three angels seated around a table that bears a chalice. The female figures form a circle evoking deep mutuality, interconnectedness, and love between one another. But the circle is open, inviting the world into this profound experience of community. As Christine Challiot, an Eastern Orthodox laywoman, wrote, “Rublev painted the three angels with a circular motion to signify their unity and equality, ‘thus creating a unity to represent the Holy Trinity in its movement of love.’”

This profound reflection is set in the biblical context of giving hospitality to the stranger. The icon depicts the story of the hospitality offered by Abraham and Sarah in Genesis 18:1-15 to three strangers. Abraham rushed to offer them hospitality—water and food.

The three migrating strangers are messengers of God. The text says simply that they were the Lord; interpreters see the three as the presence of the Trinity. And they, in turn, bring an announcement that Sarah, in her old age, will bear a son, fulfilling God’s promises. Sarah and Abraham suddenly find the tables reversed, and they are the guests at God’s table, being invited into this community of love. Thus, Catholic theologian Elizabeth Johnson explains, “This is a depiction of a trinitarian God capable of immense hospitality who calls the world to join the feast.”

This biblical story is a declaration of the unexpected, life-giving presence of God, discovered through providing hospitality to strangers. Rabbi Jonathan Sacks notes that the love of strangers is declared 36 times in the Hebrew scriptures, as opposed to the love of neighbor, mentioned only once. The love of strangers and sojourners is a primary test of one’s love for God; this is linked to the presence of migrating people, with whom we can unexpectedly encounter God in fresh and promising ways that open the future to new possibilities.

Gordon Cosby: My Mentor

Gordon Cosby was my spiritual father, not simply a brother in Christ. This relationship continued for some 45 years until his dying days. In a time when egalitarianism defines nearly all relationships as the desired norm, it’s well to remember the role of mentors who maintain, purely through their own internal integrity and faithfulness, a spiritual authority in the lives of others. Gordon Cosby was such a person to me, and to countless others.

I first encountered Gordon when I was a young legislative aide on the rise in Washington, D.C., working for Senator Mark O. Hatfield and his legislative efforts to end the Vietnam War. Disgusted with the moral vacuity of the evangelicalism that had been my heritage, but searching for faith that was more than just following a progressive social agenda, I discovered the Church of the Saviour. Gordon’s insistence that following Jesus required a disciplined inner spiritual journey always expressed in joining God’s outward mission in the world captivated me then, and ever since.

A Deeper Engagement

"Bible, Gender, Sexuality" calls us to a more honest dialogue about scripture's meaning for us today.

DR. JAMES BROWNSON'S book Bible, Gender, Sexuality: Reframing the Church's Debate on Same-Sex Relationships calls us all into a deeper engagement with the Bible itself, exploring in the most thoughtful and thorough ways not just what it says but, more important, what these inspired words of revelation truly mean.

On the one hand, Brownson argues that many of those upholding a traditional Christian view of same-sex relationships have made unwarranted generalizations and interpretations of biblical texts that require far more careful and contextual scrutiny. On the other hand, those advocating a revised understanding often emphasize so strongly the contextual and historical limitations of various texts that biblical wisdom seems confined only to the broadest affirmations of love and justice.

For all, Brownson invites us into a far more authentic, creative, and probing encounter with the Bible as we consider the ethical questions and pastoral challenges presented by contemporary same-sex relationships in society and in our congregations. In so doing, Brownson does not begin by focusing on the oft-cited seven biblical passages seen as relating to homosexuality. Rather, he starts by examining the underlying biblical assumptions made by those holding to a traditional view, and dissecting the undergirding perspectives held by those advocating a revised view.

Breaking the Impasse

It's time to reframe the church's conversation around same-sex relationships.

THE CHURCH IS locked in a polarized debate around same-sex relationships that is creating painful divisions, subverting the church's missional intent, and damaging the credibility of its witness. We've all heard the sound-bite arguments. For some, condoning or blessing same-sex relationships betrays the clear teaching of the Bible, and represents a capitulation to the self-gratifying, permissive sexual ethic of a secularized culture. For others, affirming same-sex relationships flows from the command to love our neighbor, embodies the love of Jesus, and honors the spiritual integrity and experience of gay and lesbian brothers and sisters.

The way the debate presently is framed makes productive dialogue difficult. People talk past one another. Biblical texts collide with the testimony of human experience. The stakes of the debate become elevated from a difference around ethical discernment to the preservation of the gospel's integrity—for both sides. Lines get drawn in the ecclesiastical sand. Some decide that to be "pure" they must separate themselves spiritually from others and break the fellowship of Christ's body. Then the debate devolves into public wrangling over judicial proceedings, constitutional interpretations, and property ownership. Meanwhile, the "nones," those who are walking away from any active relig-ious faith, find further confirmation for their growing estrangement.

Mirroring the dynamics of contemporary secular politics, the debate is driven by small but vocal minorities with uncompromising positions at one end or another of the spectrum. For the majority in the middle, who may be unclear about their own understandings, exploring their questions is made difficult because of the polarized toxicity of the debate. Further, those in positions of leadership in congregations or denominations come to regard the controversy over same-sex relationships as the "third rail" of church politics. They don't want to touch it. I know this because I've been there myself.

Why the Next Pope Should Come from the Global South

As the 117 Roman Catholic cardinals walk into the Sistine Chapel next month for the election of a new pope, one hopes that they fully recognize the unfolding, dramatic pilgrimage of world Christianity: The demographic center of Christian faith has moved decisively to the Global South.

Over the past century, this astonishing demographic shift is the most dramatic geographical change that has happened in 2,000 years of Christian history. Trends in the Catholic Church — comprising about 1 out of 2 Christians in the world — have generally followed this global pattern:

- In 1900, about 2 million of the world’s Catholic faithful lived in Africa; by 2010, this had grown to 177 million.

- 11 million Catholics were found in Asia in 1900; by 2010 there were 137 million Asian Catholics.

- Through colonial expansion, 59 million Catholics populated Latin America and the Caribbean in 1900; but by 2010, that number had grown to 483 million.

- In 1900, two-thirds of the world’s Catholic believers were in Europe and North America; today, two-thirds are in Latin America, Africa, and Asia.

God Is Still Not A Republican, Or A Democrat

During the 2004 presidential election season, Sojourners put out a bumper sticker with these words: “God Is Not a Republican, or a Democrat.” The number of orders was overwhelming and we kept running out. The simple message struck a chord among many Christians who were tired of the assumptions and claims by the Religious Right that God was indeed a Republican, or at least voted a straight-party ticket for the GOP. They also absurdly implied — and sometimes explicitly stated — that faithful Christians couldn’t support Democratic candidates. We said that voting was always an imperfect choice in a fallen world, based on prudential judgments about how to best vote our values, that people of faith would always vote in different ways — and that was a good thing for a democracy and the common good.

Our efforts appeared to inject some common sense into our nation’s political discourse, but given recent electoral statements and newspaper ads from some conservative Christian leaders, it appears the message bears repeating — God is still not a Republican or Democrat.

Sheer Christianity

What would our faith look like if we really put it on the line?

DURING HOLY WEEK this year, columnist and practicing Catholic Andrew Sullivan wrote a Newsweek cover story titled “Christianity in Crisis.” He argued that Christianity is being destroyed by politics, priests, and get-rich evangelists. This would “baffle Jesus of Nazareth,” Sullivan wrote. “The issues that Christianity obsesses over today simply do not appear ... in the New Testament ... It seems no accident that so many Christians now embrace materialistic self-help rather than ascetic self-denial ... [and] no surprise that the fastest growing segment of belief among the young is atheism, which has leapt in popularity in the new millennium. Nor is it a shock that so many have turned away from organized Christianity.”

My sense is that people are leaving organized Christianity because it has left behind the radical message of its founder. This has been a long and continuing struggle. Jesus taught and embodied a revolutionary, transforming love. Forsaking wealth and power, he constantly reached out to those on the margins of society. Renouncing violence, he loved not just his friends but his enemies. Condemning religious self-right-eousness and hypocrisy, he healed broken lives and opened eyes and hearts to the near presence of the kingdom of God.

The church confesses him as the risen Savior and Lord. But then, so often, it tries to domesticate him, explaining away those sharp, demanding edges of his compelling words, and finding theological excuses for not following his radical ways. We call upon people to believe in Jesus. But the question is whether we believe Jesus.