Gareth Higgins (garethhiggins.net) is a writer and broadcaster from Belfast, Northern Ireland, who has worked as an academic and activist. He is the author of Cinematic States: America in 50 Movies and How Movies Helped Save My Soul: Finding Spiritual Fingerprints in Culturally Significant Films. He blogs at www.godisnotelsewhere.wordpress.com and co-presents “The Film Talk” podcast with Jett Loe at www.thefilmtalk.com. He is also a Sojourners contributing editor. Originally from Northern Ireland, he lives in Asheville, North Carolina.

Posts By This Author

Who Is My Enemy?

I want movie bad guys to be more than monsters.

Michael Shannon and Sally Hawkins in The Shape of Water/ Kerry Hayes

I HAVE A SIMPLE view of what makes a movie great: Technical craft and aesthetic vision operating at their highest frequencies come together in service of a story or images that help us live better. How does the movie interact with what Mennonite peace theorist and practitioner John Paul Lederach calls the choice to participate in escalating dehumanization or escalating humanization? In other words, does the movie help us become less human or more? In a narrative film, do the characters’ doubts and loves, the pain they suffer, and the results of their actions leave us with a deeper sense of our own humanity?

No aspect of popular culture more urgently deserves our attention than how “enemies” are presented. What motivates “bad guys,” and how are they dealt with by “good guys”? What side is the audience on? It has been noted by some that every audience watching Star Wars wants to believe that it’s the Rebel Alliance, fighting a titanic battle against an Evil Empire. Some viewers may imagine the Empire is North Korea. Others may imagine it is the U.S. Then, of course, there is the Russian dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s clarity: that the line between good and evil runs through every person, not between us.

To See and Be Seen

Movies that challenged and movies that healed in 2017.

2017 WAS A YEAR of vulnerability at the movies, beginning with the Best Picture Oscar going to Moonlight, a film about the potential to heal broken masculinity through male tenderness, and ending with real life stories of how some men abuse power and all men need to take responsibility for changing masculine cultures of domination. Here are some of the films that meant the most to me this year and help to illuminate that onscreen journey.

First there was Endless Poetry, the 88-year-old Chilean filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky’s biographical wonder, about a mother’s love, a father’s distance, an artist’s emergence, and the wisdom of looking back and letting go.

Then, Patti Cake$, where the future of America is bright, embodied by a white working-class woman who makes hip-hop out of her struggles, an Indian immigrant so selfless that Patti Cake$’s success is what makes him happy, and an African-American street prophet raging against the machine, each falling into a community where flaws are loved.

Mother! was the most controversial film of the year: Before truth sets us free, it sometimes hurts. A lament for mistreating the Earth, which by dramatizing the burden of being the target of misogyny seeks to honor all women.

Third Way Movie-Going

We aren’t here just to be entertained, but to change how we live.

“Where did we get this capacity to imagine that horribly complicated messes have been ironed out just because someone has looked us in the eye and told us so? I don’t know about you, but I keep getting it from the movies.” So says novelist Jim Shepard in his provocative new collection of essays on movies and making the American myth, smartly (and depressingly) titled The Tunnel at the End of the Light.

In Terrence Malick’s Badlands, Shepard sees sociopathy at the root of the desire for celebrity. He also reflects on how Saving Private Ryan was a “war movie found pleasing by conservatives and liberals, and it’s not hard to figure out why: ... more than enough war is hell to satisfy the left, and ... an even greater helping of well, it may be hell, but it sure brings out the best in us, doesn’t it? raw meat for the right.” Shepard makes a useful point— something can be remembered by one group of people as the antithesis of how another sees it.

Being Present to the Present

Contemporary movies are more psychologically nuanced and sociologically diverse than ever.

A FEW YEARS AGO, Woody Allen made a subtle cinematic joke about writers and artists harking back to “the good old days,” while soaking up—and co-creating—the atmosphere of 1920s Paris. If ever there was a “good old days,” some might think it was 1920s Paris. The joke of Midnight in Paris was that even people who live in the good old days are nostalgic for their own version. People feel the same way about movies: “They don’t make them like they used to” is the common refrain.

A Caper Film with More

Steven Soderbergh hits the mark between red-blue reconciliation and comedy.

LOGAN LUCKY, the new film from Steven Soderbergh, is a delicious surprise. It’s about working-class Southerners robbing the Charlotte Motor Speedway during a NASCAR race, and its weaving of the intricacies of planning, executing, and living in the post-heist glow is hilarious and even warm.

More than that, it’s a heist film in which ordinary people (not slick, hypermasculine Armani warriors) employ imagination instead of heavy artillery to take money from an institution that doesn’t need it anyway. The fact that the target of the theft got the money through selling overpriced, undernourishing food and drink is only one piece of bonus philosophical content. It’s a rare thing: a thoroughly entertaining movie with real things to say about the moment it is released. At a time when left-right political division in the U.S. has intensified, Soderbergh, a Southerner who works from New York, has made a red-blue reconciliation comedy.

Critical Connections

Ken Hanke was a critic who believed in his own opinions, but didn't impose them on others.

GOOD VIBRATIONS is a brilliant roof-raising musical from 2012 about making a difference in the world by being yourself. It’s the kind of film that makes you fall in love with life. And it was the last movie about which Ken Hanke and I wholeheartedly agreed.

Hanke, our local newspaper film critic in Asheville, N.C., recently passed away at the too-young age of 61. His byline identified him as “Cranky Hanke,” but he had a generous heart. He knew that good film criticism requires knowing three things, at least: something about cinema, something about how to write well, and something about life. The first of these comes naturally to people who watch enough good movies. The second is part gift to be channeled, part skill to be nurtured. As for the third, well, we all know something about life—the trick is whether or not we’re willing to let what we know of ourselves be known in our work.

Ken Hanke was a critic who believed his own opinions, but didn’t impose them on others. He understood film criticism as a conversation between movie and audience, in which being right isn’t as important as being authentic.

This kind of critical engagement is often ignored in favor of mere criticizing—reacting, not responding, snap judgments instead of considered reflection. “That’s one of the worst things I’ve ever seen” limits the possibility of conversation to discover more of what the movie might be inviting us to. I want to know why you think it’s the worst (or best). I want to be invited into a conversation about authenticity and what it is to live better in the light of what artists and other provocateurs are trying to tell us.

Plain Talk

The notion of enemies sitting down and talking with each other is at the heart of the new Icelandic film Rams.

When Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev met in what has been seen as the beginning of the end of the Cold War, the venue was an unassuming house overlooking the sea in Reykjavík, Iceland. Höfði House had been previously occupied by the poet Einar Benediktsson, who once wrote, “Take notice of the past if you would achieve originality.” Whatever else Einar meant, at this house, the necessity of learning from history can’t be ignored.

It is easier to imagine today’s enemies talking once you’ve seen the house. You see, it’s not the Avengers’ home base or one of those underground lairs favored by James Bond villains. It’s just a house, surrounded by the typical trappings of a small city—business headquarters, cafes, supermarkets. The Icelandic government uses it today for social gatherings. And what happened in it 30 years ago was at heart two people communicating, with a shared goal that transcended them both.

The notion of enemies sitting down and talking with each other is also at the heart of the magnificent new Icelandic film Rams, which I saw in a cinema about five minutes’ walk from Höfði. Two sheep-farming brothers live and work beside each other, but haven’t spoken for four decades. A family shadow has driven them apart—one of those decisions made by parents seeking the best for their children but not knowing how to arrive there. And so, separately, the brothers endure twice the hardships and experience only half the blessings of life amid this most exquisite landscape. Success is ignored by the other, or serves as an occasion for jealousy rather than celebration; Christmas is spent alone, no one to share the feast, and Icelandic winters are hardest of all.

Welcome to the Jungle

Human beings get the chance to discern the difference between the false and true self.

THE MOVIES AND MEANING community recently published our list of greatest films, based on the idea that in a great film the highest aims of craft and the most humane visions meet. It seeks a “third way” between one reactionary notion, that art should be judged on the basis of what it portrays rather than how it portrays it, and another—that content is morally neutral. I say bring it all: love and pain and action and laughter and grief and sex and violence and horror and contemplation. To extend Roger Ebert’s notion, a movie is not only about what it’s about, but it’s also about how it’s about it.

The most beloved films on our list include The Tree of Life (in which the most enormous, transcendent existential questions mingle with the most ordinary of tragedies and blessings), Lone Star (which aims for nothing less than the healing of U.S. memory, for survivors and perpetrators alike), and Wings of Desire, Beasts of the Southern Wild, and Spirited Away (which use magic and the supernatural to remind us of the miracle of everyday life). The top 10 also includes Schindler’s List—a testament to monstrous suffering and extraordinary courage alike—and the Three Colors trilogy, which does the seemingly impossible: take a national political virtue and fully embody it in the life of an individual.

The new version of The Jungle Book is too recent for the list and hasn’t had the chance to prove its staying power, but what a glorious surprise it turned out to be. The beloved 1967 cartoon is held in great affection, but affection that requires turning a blind eye to its colonialist and racist undertones—particularly the literal aping of some black cultural tropes by a character presented as nonhuman, whose greatest desire is to “be like you.” The 2016 version works to transcend white supremacy and even critiques human interference with the rest of nature. When a villain comes to a violent end, it’s not through the hero’s superior strength but through the bad guy’s own selfishness.

The Crosshairs of a Dilemma

Eye in the Sky doesn't offer easy answers, only difficult questions.

STANLEY KUBRICK’S Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb was released in 1964, and it was echoed later that year by a film on a similar topic, Fail-Safe. Directed by Sidney Lumet, Fail-Safe imagined the idea of a nuclear explosion being unpreventable by the people supposed to be in charge of it. Strangelove is hilarious but chilling satire; Fail-Safe is just chilling. The central notion, that ethics can’t be trusted to machines, lingers today: George Clooney produced a live television version of Fail-Safe as recently as 2000.

A current version of the dilemma is brilliantly portrayed in Eye in the Sky. Cutting between four main locations (a British government committee room, a military control center in the English countryside, a Nevada drone piloting bunker, and the Kenyan house from where a suicide bomb attack may be launched), it’s like a relentless tennis match in which the crisscrossing ball is a matter of life and death.

Who decides who can be killed? If blowing up the house will prevent an attack that might kill 80 people, how much does it matter that a little girl selling bread nearby will probably die too? What is legal? Does “legal” mean “right”? Such questions have rarely been handled with such compelling dexterity in a movie. Eye in the Sky deserves comparison with Dr. Strangelove and Fail-Safe because it doesn’t offer easy answers, only difficult questions, and its seamless movement between locations fully immerses the audience inside the debate. But it transcends those earlier films because of the way it treats the characters that might be seen as “other.”

Mocking Pretentious Power

If comic portrayals of bad leadership are comforting, serious cinematic explorations of bad leadership might help us learn how to avoid it.

EXTRAORDINARY British actor Mark Rylance has a noble theatrical reputation but has only recently found prominence in movies, most notably in the wonderful Steven Spielberg Cold War film Bridge of Spies, for which he recently won the best supporting actor Oscar. Speaking of Spielberg, Rylance made a beautiful point: “Unlike some of the leaders we’re being presented with these days, he leads with such love that he’s surrounded by masters in every craft.” This gentle wisdom—that good leaders attract good teams—echoes the message of Bridge of Spies, which illuminates the possibility of talking to each other across boundaries of militancy, misunderstanding, and fear. It is an invitation to loving leadership, criticizing a mutually destructive strategy by practicing something better.

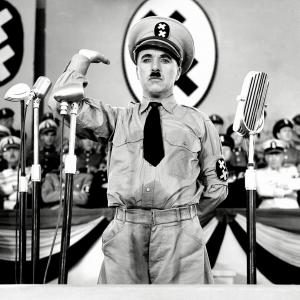

Amid the noise of “some of the leaders we’re being presented with these days,” I’ve been indulging in a little comfort-watching, asking Charlie Chaplin to help me discern a way through. Chaplin’s brave, hilarious, and deeply moving film The Great Dictator does to authoritarianism what C.S. Lewis says the devil cannot tolerate: It mocks evil, revealing its pretensions. Chaplin’s courage has rarely been matched. Today his mantle may be held by Sacha Baron Cohen, whose trilogy of pride-puncturing, diversity-affirming films, Borat, Brüno, and especially The Dictator, is brave enough to challenge prejudice when it’s not safe to do so. These three are in the same tradition as Dr. Strangelove, In the Loop, Four Lions, Dave, and the Marx Brothers’ Duck Soup, which make us laugh at the absurdity of political control, taking away some of its power.

If comic portrayals of bad leadership are comforting, serious cinematic explorations of bad leadership might help us learn how to avoid it. Nixon, Downfall, the Godfather trilogy, Citizen Kane, The Apostle, Beasts of No Nation, The Act of Killing, Leviathan, and There Will Be Blood all present warnings of what happens when leaders are self-interested, unaccountable to an emotionally mature community, and not mentored in tending to their inner lives.

Halfway to Brilliant

The Revenant can't decide if "an eye for an eye" is preferable or merely inevitable.

WATCHING THE much-awarded film The Revenant is an ordeal, but its director Alejandro G. Iñárritu’s films have such energy and compassion that I hoped the payoff would be worth the stretch. Iñárritu’s early films Amores Perros and 21 Grams rehumanize characters who make bad choices, with an attention to scale that might be described as Napoleonic.

The Revenant is the loosely historical tale of Hugh Glass (Leonardo DiCaprio), an early 19th century fur trapper left by his companions for dead after a bear attack, agonizing his way to track his betrayer (Tom Hardy) through some of the most frozen wilderness in cinema. The commitment of DiCaprio and Hardy has been rightly applauded—this is a cold and exhausting way to make a film. And the craft is monumental—arrows seem to land on the audience, the bear attack is terrifying, the camera hardly ever stops moving. But the exploration of the futility of revenge at the heart of this story is confused.

Faith From Many Angles

Films from 2015 that illuminate religion and spirituality.

AS THE Academy Awards approach, I’d like to mention some films worthy of recognition by the lights of a different set of criteria. As a member of the Arts and Faith Ecumenical Jury, I am delighted to present our list of films from 2015 that “challenge, expand, or explore” faith, including those that illuminate religion and spirituality, pointing to a more humane vision of the world.

The choices are much more diverse than the usual annual polls. Multifaith stories (Irish Catholic, Israeli Jew, Iranian Muslim, just to start), exposés of injustice and calls for restoration, exile, and return, the damage done by immature religion, and the possibility of human spiritual evolution—all are here. And the film we agree was the year’s best does something profoundly important: It tells the story of a weaponized individual who spends her time doing everything she can to avoid killing.

Some in our top 10 I’ve written about here before—our number nine is the fun and wise animated map of the emotions, Inside Out; eight is the immigrant tale Brooklyn; five is Brian Wilson mental illness and creativity biopic Love & Mercy; and four is the powerful investigative journalism drama Spotlight, a challenge to contemporary news media to once again pursue their higher calling to tell the truth for the common good. Here are the rest of our selections:

10. About Elly. Iranian filmmaker Asghar Farhadi made this film in 2009, and it has been acclaimed as heralding “a new genre,” but it was not released in the U.S. until last year. Farhadi’s magnificent, compassionate dramas A Separation and The Past are more recent, but his ability to tell the most humane stories in the most gripping way was forged here.

The Best of 2015

Here are my picks for the best films of 2015.

HERE ARE my picks for the best films of 2015. Honorable mentions for Creed’s operatic dignity and subtle advocacy of racial reconciliation; The Forbidden Room’s unabashed creative inspiration; Mad Max: Fury Road for being a pro-feminist action film; Spectre for James Bond going beyond an eye for an eye; Grandma, Lily Tomlin’s crowning achievement as an actor embodying that it’s okay to be different; and Room, part-thriller, part-existential exploration, honest about trauma and the lengths love will go to protect the vulnerable.

10. Shaun the Sheep. A delightfully inclusive, breathtakingly crafted story about humans, animals, and nature as one family. With frenetic comedy and an open heart, it honors the marginalized, critiques superficiality, and even lets the villain live to learn his lesson.

9. Me and Earl and the Dying Girl. An indie comedy-drama that avoids cliché and makes heroes out of nerds.

8. Beasts of No Nation. Evoking Apocalypse Now, a harrowing story of child soldiers, the legacy of colonialism, and how violence is transmitted from one generation to the next.

7. Clouds of Sils Maria. A stark reflection on identity and the conversation each of us has with the voice(s) in our head. Olivier Assayas’ film asks if we are living from the inside out or for external reward.

6. Brooklyn. A poetic and compassionate painting of the paradox of finding home as an immigrant.

The Uninitiated

In allowing Steve Jobs to be selfish, Steve Jobs may make us look at ourselves.

wongwean / Shutterstock

MICHAEL FASSBENDER'S uncanny performance as Apple Inc. co-founder and CEO Steve Jobs begs the question of how someone so clueless about human relationships could win the hearts of so many people. Of course, the performance and the Aaron Sorkin script it’s based on are not the same thing as the man himself. Steve Jobs may be unfairly treated by Steve Jobs. The question of its accuracy is not unimportant, and people who knew him deserve a hearing. But the film only sketches a persona rather than providing an encyclopedia of the soul.

Treating Steve Jobs as a film about power and personality evokes the Quaker teacher Parker Palmer’s notion of an “undivided” life. Palmer quotes Rumi’s warning, “If you are here unfaithfully with us, you’re causing terrible damage.” One facet of this unfaithfulness is the difference between living “from the inside out” and living primarily for external reward. Undivided lives are punctuated by initiatory experience, familiar to our ancestors, and now re-emerging in communities such as the ManKind Project and Woman Within. Initiatory experiences take people into the depth of their psyches, supported by wise elders, opening a crack that lets in the light of transformation. Initiated egos thrive in balanced service to the highest self and the common good (so the wise elders tell me).

The Steve Jobs in Steve Jobs has no such initiation—he seems basically the same shallow egotist at the end of the movie as he was at the start. The joy of Steve Jobs is the kinetic dance of image and sound, and actors at the top of their game (Kate Winslet as the definition of long-suffering colleague, Seth Rogen in a rare dramatic role, and Michael Stuhlbarg, all of them representing prickly conscience). The problem of Steve Jobs is that it omits engagement with the personal transformation that many think unfolded for him as his products achieved something like omnipresence. There’s no initiation here, unlike in Bridge of Spies, where Tom Hanks risks his life to negotiate a prisoner swap in a gripping, if light, Cold War thriller. Mark Rylance’s accused Soviet spy emerges more humanized than Jobs’ community-building entrepreneur.

A Step into Beauty

Authenticity is what matters, not how "elite" the work can appear to be.

Songquan Deng / Shutterstock

When I first saw the DeLorean rush toward me at the end of Back to the Future, I was 11 years old, and I felt alive in a way that I’m not sure I had experienced before. The endings of the films of Robert Zemeckis would continue to give me that rush of good feeling—Tom Hanks at the crossroads in Cast Away, and on the tree stump waiting for his little son to come home from school in Forrest Gump; Denzel Washington faced with the question “Who are you?” in Flight. Some critics, believing that things need to be difficult in order for them to be good, find it easy to turn down a Zemeckis invitation. I beg to differ—there’s no contradiction in loving the populist sentiment of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, the serious melodrama of The Elephant Man, the painful and nonlinear narrative of Exotica, the surreal plunge into the human shadow of Enter the Void, and the high art intellectual sensibilities of Eternity and a Day. And those are just a handful of very different films beginning with the letter “E.” Authenticity is what matters, not how “elite” the work can appear to be.

Zemeckis makes large-scale populist entertainment that makes us laugh and cry, but he deals in authenticity. Along with the fun and the flights (Forrest running across the U.S., Marty McFly and Doc Brown’s race to connect the wires with the clock tower, and two of the most harrowing plane crashes in the movies), emotional beats are earned, characters behave as they might in real life (even if they are in a time-traveling sports car or abandoned on an island), and audiences get the chance to wrestle with the same question faced by Denzel: Who am I?

Form Follows Function

The best films help us understand how to transcend our brokenness without excluding our shadows.

Sergey Mironov / Shutterstock

MY FRIEND the architect Colin Wishart says that the purpose of his craft is to help people live better. Just imagine if every public building, city park, urban transportation hub, and home were constructed with the flourishing of humanity—in community or solitude—in mind. We might be inspired to create new, hopeful thoughts, friendships with strangers, or projects that bring transformation into the lives of others.

It is easy to spot architecture divorced from its highest purpose. In a building or other space made to function purely within the bounds of current economic mythology—especially those created to house the so-called “making” of money—the color of hope only rarely reveals itself. Instead we are touched by melancholy, weighed down by drudgery, compelled by the urge to get away. But when we see a space whose stewards seem to have known that human kindness, poetry, and breathing are more important than the “free” market, we realize that it is possible to be always, everywhere, coming home. Think of a concert hall designed for the purest acoustics, a playground where the toys blend in with the trees, a train station where the transition from one place and way of being to another has been honored as a spiritual act.

Feeding the Inner Life

Our deeper hunger is for stories that strive to tell the truth about life and its possibilities, that demand self-reflection, and that permit subtexts to breathe so we can fill in the gaps.

THE TEACHER Edwin Friedman believed that good leadership creates conditions for people to find tools to become emotionally mature. In other words, no matter what its stated goal (civil rights, community organizing, religious engagement), the most important purpose of leadership is to help us become more fully human.

Of course this is also true for artistic endeavors—stories that create emotional dependency in audience members are not offering good leadership, and they usually make for bad art too. We may like them, as they satisfy the surface-level desire for easily grasped narratives and quick resolution. But that’s the aesthetic equivalent of a cheap burger. Our deeper hunger is for stories that strive to tell the truth about life and its possibilities, that demand self-reflection, and that permit subtexts to breathe so we can fill in the gaps.

I saw three such films recently. Inside Out displays astonishing imagination, bringing us into the human psyche to figure out how we think. There’s genius in a story that gives the five core emotions personalities, wisdom in how it makes honest work of how people confront change, and a delightful bonus in the form of Bing Bong, a character with all the lovableness of Baloo the Bear and a purpose with which Carl Jung would be pleased. Inside Out offers no shortcuts to spiritual well-being. It’s film-as-therapy that’s as entertaining for kids as it is wise for adults (and vice versa).

Projecting Possibility

The purpose of art is to help us live better.

The purpose of art is to help us live better.

The Ultimate Threat

Too much is going on, and not all of it is good.

AVENGERS: AGE OF ULTRON asks what happens when you give a computer the ability to think for itself. To which we could add, what happens when you make a science fiction film that assumes the audience can think for itself?

Sadly, in the case of Age of Ultron, writer-director Joss Whedon’s serious attempt to make a smart blockbuster collides with corporate cookie-cutting and the belief that stockings are best overstuffed, even if what’s in them is just cotton wool or dead weight. Too much is going on, and not all of it is good. Thor, the Hulk, Iron Man, Black Widow, and the other guy with the arrows are still looking for a magical object, but when they find it we’re none the wiser about what it’s for. Bad guys still threaten the safety of the world, and the Avengers still think that only maximum force can secure a result.

Maria and the Rabbi

Lest we forget, "The Sound of Music" is a story of hope triumphing almost unimaginable odds.

IT’S THE 50TH anniversary of The Sound of Music. I never thought I’d write about it here, but someone recently offered me the kind of gentle admonishment that Maria might have given to the von Trapp children. Maria is usually right, and my friend is too. One of the wisest film critics I know, a man dedicated to contemplation and activism and who doesn’t shy away from the more challenging edges of cinema, still considers it his favorite film.