Eboo Patel is founder and executive director of the Interfaith Youth Core, a Chicago-based international nonprofit that promotes interfaith cooperation. His blog, The Faith Divide, explores what drives faiths apart and what brings them together. He is also author of Acts of Faith: The Story of an American Muslim, the Struggle for the Soul of a Generation (Beacon Press, 2007).

Posts By This Author

The Problem with Prejudice

Consider for a moment what might have happened if the forces of anti-Catholic prejudice had won.

ChameleonEye / Shutterstock

POPE FRANCIS arrived in the United States amid a flurry of talk about Muslims. There was Ben Carson’s statement that he would not want a Muslim to be president. There was The Donald’s promise that a Trump administration would look into the supposed network of Muslim terrorist training camps in the United States. And there was young Ahmed Mohamed in Texas, who got suspended from school and shackled in handcuffs when his science project was mistaken for a bomb. Maybe the police were concerned that he’d designed it in one of those fictitious terrorist camps.

It appears that many Americans are in a panic about the prospect of a Muslim takeover.

Domination by a foreign religion is an old anxiety in America. As we hang on every word Pope Francis utters, it is interesting to note that for much of our history a driving fear was that Catholics would amass significant political power and the pope would fly his flag at the White House. “Our freedom, our religious freedom, is at stake if we elect a member of the Roman Catholic order as president of the United States,” Norman Vincent Peale warned in September 1960 about John F. Kennedy’s candidacy.

With 30 percent of Congress now claiming to be Catholic, six Catholics sitting on the Supreme Court, several Catholics occupying high office (including the vice president, the secretary of state, and the speaker of the House), and a pope with much to say about major policy issues, that particular apocalypse appears to have arrived.

Mostly, it has been met with applause. The papal flag was indeed flying at the White House during the pope’s arrival ceremony—several thousand of them in fact, more than a few in the hands of the many non-Catholics in attendance. Recent surveys show that Catholics, along with Jews and mainline Protestants, are among the most well-liked religious groups in the United States.

An Evangelist for Engagement

He found himself wondering whether "sin and heathenism" were the correct terms for a tradition that could inspire such beauty.

THIS YEAR MARKS the 50th anniversary of the Vatican II document Nostra Aetate, the 1965 proclamation on “the relation of the church with non-Christian religions.” I want to celebrate a great theologian whose life intersects with that moment and whose work exemplifies its ethic.

Paul Knitter grew up in a strong working-class Catholic family on the South Side of Chicago and felt the call to the priesthood in his early teens. After four years of seminary high school and two years of additional novitiate training, he joined the Divine Word Missionaries (or SVD), an order whose main work was bringing non-Catholics into the Catholic faith. His regular prayers included the line “May the darkness of sin and the night of heathenism vanish before the light of the Word and the Spirit of grace.”

Reflecting back on this practice in his book One World, Many Religions, Knitter writes: “We had the Word and Spirit; they had sin and heathenism. We were the loving doctors; they were the suffering patients.”

Knitter’s journey took a number of unexpected turns. As he sat with the other seminarians listening to the stories of returned SVD missionaries, he discovered that he was fascinated by the slide shows of Hindu rituals and Buddhist ceremonies. He even detected a hint of admiration in the voices of older SVD priests as they described the elaborate non-Christian religious systems that they encountered on their missions. One brought in an Indian dance group and explained that their performance was developed in a Hindu context but had been adapted to glorify Jesus. Knitter was entranced by the intricacy of the movements, and he found himself wondering whether “sin and heathenism” were the correct terms for a tradition that could inspire such beauty.

A Model for Higher Ed

Admission requirements at Berea include being smart, being willing to work hard, and being poor.

Frannyanne / Shutterstock

IN A BID to relive our traveling days, my best friend from college and I took a weekend road trip to Berea, Ky., to check out a folk music festival. We got to be dancing fools again for one beautiful, moonlit night, imbibing hippie music to our hearts’ content.

We also got a heart full of something else—a little thing called the American Dream.

In addition to being home to a cool new music festival, that little holler in Kentucky is home to Berea College. I’ve stepped foot on more than 100 campuses in my 10-plus years running Interfaith Youth Core. Berea is unique.

Maybe it’s because it was started in 1855 by a slave owner’s son as an interracial, co-educational school seeking to live out the school’s motto, drawn from the book of Acts, “God has made of one blood all peoples of the earth.” Maybe it’s because the admission requirements include being smart, being willing to work hard, and being poor. Maybe it’s because the tuition is free. Maybe it’s because all students have a 10-hour-a-week campus job, ranging from office work to janitorial work.

Yes, you read all that right. A man whose family owned slaves took the Bible seriously enough to risk his life to start a college that educated blacks and whites and men and women, together, a decade before the civil war came to a close.

Christian Nation vs. Secular Country?

"The old hatreds shall someday pass; the lines of tribe shall soon dissolve."

AS WE SWING into the 2016 presidential campaign, we Americans can be certain of at least one thing: We will be treated to another round of very public arguments about the role of religion in our republic. If this were a boxing match, and if past patterns persist, the title of the bout would be Christian Nation vs. Secular Country. The sides, more eager to mobilize their own than have a conversation with the other, will happily seek to bludgeon one another.

Thankfully, a number of writers have set out to complicate this picture in a way that adds both color and hope. Peter Manseau’s One Nation, Under Gods and Denise Spellberg’s Thomas Jefferson’s Quran are beautifully written accounts of our interfaith country. By interfaith, I mean both that there were people of different faith persuasions present from our earliest days, and that they constantly bumped into one another as they established their communities and sought to build up this country.

Is the Language of Business Enough?

If we are closed to faith language, we may find ourselves burned up and frozen out.

I’M PRIVILEGED to be part of a program called the Prime Movers Fellowship, a circle of mainly younger-generation social change agents launched by Ambassador Swanee Hunt and her late husband, Charles Ansbacher. In December, the Prime Movers had a retreat with the Council of Elders, an inspiring group of civil rights era activists. Those two days contained some of the most profound conversations I’ve been part of in 10 years.

Rev. Joyce Johnson facilitated masterfully, opening sessions with prayer and sacred song. Rev. John Fife spoke about launching the Sanctuary movement through churches. Rabbi Art Waskow connected the theme of the Eric Garner killing (“I can’t breathe”) with the climate challenge (“We can’t breathe”).

Rev. Nelson Johnson of the Beloved Community Center told a story about driving into the North Carolina mountains to try to convince a white supremacist to cancel a Ku Klux Klan rally in Greensboro. “I was driving alone,” he explained, “and halfway up the mountain I started to get a little scared. So I stopped my car and got down on my knees to pray. I felt God tell me I was doing something necessary, and I felt my courage return.” He got back into his car and drove on to the meeting.

People Get Ready

If Jen Bailey is emblematic of her generation in any way, we have a lot to be hopeful about.

JEN BAILEY PAYS attention. She recognized the paucity of healthy food choices in Nashville’s “food desert” areas and designed an interfaith toolkit to enhance the skills of food- justice organizers tackling that issue. Jen — now Rev. Bailey of the African Methodist Episcopal Church — listened to the recurring theme in her own lived experience: Faith communities can be a catalyzing source for good and are even more powerful when they work together. Bailey hasn’t yet hit 30.

Millennials have gotten serious press this year from Pew, NPR, The Huffington Post, The Atlantic, and the like. Amid their diversity, these roughly 80 million people appear to share several common traits. They are global citizens who want to act and impact locally, who crave meaning, seek entrepreneurialism, prioritize people and networks over institutions, and often profess different parameters of and pathways to success than previous generations. If Bailey is emblematic of her generation in any way, we have a lot to be hopeful about.

This year, Bailey started the Faith Matters Network (FMN), a “multi-faith alliance dedicated to building the power of people of faith to transform our social and economic systems.” The group focuses on the South and Midwest because both areas are significantly impacted by economic inequality and are highly religious. That is, there is a lot of work to be done and lots of people (theoretically) committed to doing it.

On Being A Muslim Parent

Would his first taste of Islamaphobia come at the age of 5 during show-and-tell?

LAST YEAR, as I was unpacking my son’s school backpack, I found the children’s book on the Prophet Muhammad that my wife and I read to him at night. He had brought it to school without telling us. “It was for show and tell,” he explained to me.

You might think that my first reaction would be happiness. One of my goals as a Muslim parent is to help my kids feel connected to their faith. Clearly my son felt close enough to his religion to bring a book on the Prophet to share with his class.

What I actually felt was a shock of fear shoot down my spine. It was an immediate, visceral reaction. A whole slew of questions raced through my head. What did his teacher think of Muslims? What about his classmates? Would somebody say something ugly or bigoted about Islam during my son’s presentation? Would his first taste of Islamophobia come at the age of 5 during show-and-tell?

My fear at that moment is one small window into what it feels like to be a Muslim-American parent at a time when Muslim extremism is on prominent display and Islamophobia in America continues to spread.

A Theology of Interfaith Cooperation

We can work with others even while disagreeing on significant issues.

SUMMER IS READNG time and there’s nothing I like more during the warm months than delving into geeky works on religion. This summer, Peter L. Berger and Brian D. McLaren have topped my list.

In a set of recent essays, Berger emphasizes that relativism and fundamentalism are two of the most prominent religious paths in the world today. Here’s my one line definition of fundamentalism: “Being me is based on dominating you.” And my simple definition of relativism: “I no longer know who I am when I encounter you.”

For Berger, while relativism and fundamentalism are at opposite extremes, they are actually closely connected in that they are both “products of the same proc-ess of modernization.” As he first wrote decades ago in his book The Heretical Imperative, frequent and intense encounters between people with different identities is the signature characteristic of the modern era. In Berger’s pithy phrase: modernity pluralizes.

Berger continues, “pluralism relativizes ... both institutionally and in the consciousness of individuals.” In the pre-modern era, institutions, ideas, and identities had a largely taken-for-granted status. For most of human history, the vast majority of humankind had little to no choice about which institutions they were going to participate in or what their identities were going to be. Such matters were experienced as fate.

The Strength to be Uncool

A lot of problems stem from people lacking the courage to follow their moral core.

DURING THE WINTER of my sophomore year in high school, a fistfight broke out in the cafeteria. It wasn’t anybody I knew especially well, and it didn’t get very far, but it marked a day in my life I’ll never forget.

Once the commotion started and the chant of “fight, fight, fight” rose up in the lunchroom, everybody stood to cheer and watch. I did too, craning my neck to try to see better, probably wearing a sophomoric smirk on my face. It felt to me as if the whole world had gotten to its feet.

Everybody except one person. I only noticed when it was over and all of us turned to sit back down. My friend JJ hadn’t budged. Judging by the fact that his sandwich was almost gone, he hadn’t even let the matter affect his lunch. He didn’t ask any questions about the fight—not who was involved, not whether there was blood, not who won—he just bit into his apple.

The rest of us tittered on about the whole thing. Who we were rooting for, whether it would continue at the park after school, blah blah blah. JJ just stared off into space.

Finally, the contrast felt too much for me, and I said, “Hey JJ, why didn’t you get up?”

“I don’t like fights,” he responded. Then he looked me straight in the eye and said, “You don’t like fights either.”

Studying Interfaith Leadership

This may be a field whose time has come.

CAN YOU GO to school to become an interfaith leader? An increasing number of faculty, staff, and students on campuses believe the answer is “yes.”

Interfaith leadership courses are starting to crop up at colleges across the country. At New York University and Nazareth College, you can even get a minor in the area. The organization I lead, Interfaith Youth Core, recently organized a conference for university faculty interested in this area. We expected 30 people to show up, and got nearly 120. This all suggests that this may be a field whose time has come.

Academically speaking, “interfaith leadership” is part of the larger field of “interfaith studies.” Just as you might study education at a university to become a teacher, in the future you will be able to take coursework in interfaith studies in preparation for a career in interfaith leadership.

Interfaith studies looks at the myriad ways that people who orient around religion differently interact with one another and considers the implications of that interaction for everything from personal lives to global politics. It’s a field that asks questions such as: In what religious groups is the intermarriage rate growing fastest, and what are the distinctive dynamics of such relationships? What types of political arrangements seem to foster positive interaction between faith communities, and what types are associated with interreligious tension? How effective are current religious education programs in forming young people in faith traditions?

'Nones' and the Common Good

What will happen to U.S. civil society as the pews empty out?

THIS IS NOT a column full of hand-wringing about the moral decay of U.S. society. Nor is it about my concern for the souls of my fellow citizens who are atheists, agnostics, or some other stripe of nonbeliever. I am worried about the growing number of religious “nones” in the United States, but not for those two reasons.

Let me be clear about something before continuing: Many of the people I love and admire most are religious “nones”—those who indicate “none of the above” on religious preference surveys. They include people of high intellect, great sensitivity, and deep character. In fact, many of them could give lessons in such areas to some of the religious people I know.

What they do not do is build hospitals, schools, colleges, or large social service agencies. Such institutions (when not built by the government) have generally been founded and supported by religious communities in the United States. This is not so much because religious people are always better human beings; it’s because religious communities value and organize such work at significant scale.

Religious communities play a profound role in U.S. civil society. About one out of every six patients in the U.S. is treated by Catholic hospitals. Most, if not all, have some sort of explicit commitment to serving the poor because of their faith identity. There are nearly 7,000 Catholic grade schools and high schools in the U.S., and more than 260 colleges. This is to say nothing of the refugee resettlement, the addictions counseling, or the services for homeless men and battered women provided by Catholic social service agencies.

A Daringly Astute Faith

Just like that, the pope had gotten to the heart of Islam, my religion.

EARLIER THIS FALL, I had the good fortune to speak at St. Martin’s University, a Benedictine school on a beautiful campus about 90 minutes south of Seattle. Our campus guide was Jennifer Fellinger, a woman who was raised Catholic and attended Xavier (a Jesuit university in Cincinnati), but had drifted a bit. She didn’t feel pushed away; she’d just been caught up in the madness of family life and work, and faith had slipped away from her center.

And then Pope Francis spoke. Or rather, gave an interview that was published by Jesuit magazines across the world. Her voice cracked as she described how that interview had returned the light of her faith to the center of her life.

On the drive from Sea-Tac airport to Lacey, Wash., where St. Martin’s is located, Fellinger quoted long segments of it from memory. Her favorite part was toward the end of the long interview when Pope Francis described Catholicism as a “journey faith” rather than a “lab faith.” She loved the story the pope told about being sick in the hospital with lung disease, and having the doctor come by and clinically prescribe him a certain dose of medicine. The sister who was on duty tripled the dose because she had a visceral sense of how he felt, as she was around sick people all day. It was a great example of the wisdom of presence and the gentleness that comes with simply being with people. The pope had called this sister “daringly astute.” Jennifer loved that. “This is what my Catholic faith is about, this is what I am striving for when I am faithful—to be daringly astute,” she exclaimed.

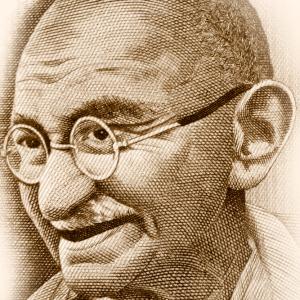

Mapping Gandhi's Faith Journey

How did a skinny, shy, middle-class Indian come to lead one of history's great liberation struggles?

MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. once said that the greatest Christian of the 20th century was not a member of the church. He was referring to Mohandas Gandhi. A remarkable number of King’s fundamental beliefs—the use of active nonviolence as a tool of social reform, the commitment to loving one’s enemies—can be traced back to the influence of Gandhi, which means that one of the defining figures of 20th century American Christianity was profoundly shaped by the example of an Indian Hindu. As King said in 1958 of the civil rights movement, “Christ furnished the spirit and motivation while Gandhi furnished the method.”

But what of Gandhi’s influences? How did a skinny, middle-class, mid-caste Indian, so scared of public speaking as a student that a classmate had to read his speeches aloud for him, come to lead one of the great liberation struggles of the past century? A new book by Arvind Sharma, professor of comparative religions at McGill University, makes the case that the source of Gandhi’s strength was his spirituality. And while the heart of Gandhi’s faith was Hindu, as King’s was Baptist, the influences were remarkably diverse.

Pointing out that most of the biographies of Gandhi really tell the story of Mohandas Karamchand (the name he was given by his family), not Mahatma (a title that means “great soul” and is given to saints in India), Sharma’s book Gandhi: A Spiritual Biography sets out to give an account of the Mahatma. Sharma quotes Gandhi directly on the importance of highlighting the dimension of spirituality in any attempt to understand him: “What I want to achieve—what I have been striving and pining to achieve these 30 years—is self-realization, to see God face to face, to attain moksha [the Hindu term for liberation]. I live and move and have my being in pursuit of this goal.”

Hot Dogs for Peace

I felt the horror of a kid caught in a grade school coolness competition.

WHEN I WAS growing up in the western suburbs of Chicago, I felt so far outside of the inner circle of cool kids that I didn’t even know where the circle was. So you can imagine my delight when I got an invitation to David’s birthday party. David was in the outer part of the inner circle, which meant I was heading in the right direction.

A couple days before the party, my mom took a closer look at the invitation and noticed that it said David’s parents would be making hot dogs for lunch. As she wasn’t sure whether the hot dogs were pork or beef, and as we were Muslims who don’t eat pork, she informed me that she’d be giving me all-beef franks to take from home with a note to David’s mom asking her to fry them up in a separate pan.

Of course, this horrified me, the kind of horror that only a kid caught up in the jungle of grade school coolness competition can feel. I remember standing in the living room, staring at my mom, and thinking to myself: “First, you named me Eboo.”

The day of the party rolled around and, dutiful Indian-Muslim child that I was, I accepted the little plastic baggie with two beef hot dogs that my mom handed me, allowed her to put me in nice slacks and a collared shirt, and went off to the party. When lunchtime came, I snuck into the kitchen to make my request of David’s parents. Imagine my surprise when I noticed another kid in the kitchen. He wore a collared shirt and nice slacks and also held a plastic baggie with two hot dogs.

From Diversity to Pluralism

Bridges don't fall from the sky; people build them.

THE TERM “DIVERSITY” in professional and educational circles in the United States is frequently mentioned as positive on its face, needing no justification. “Diversity is our strength” or “diversity enriches us” are common statements.

But Harvard professor of comparative religion Diana Eck points out that diversity is simply a demographic fact—a situation in which people with different identities live in close quarters. The term says nothing about how those people get along with one another. Frankly, if all we knew about religious diversity in particular were the stories carried on the international news, it would be hard to conclude anything except that the close gathering of Muslims, Christians, Jews, Buddhists, Hindus, and others is nothing but a recipe for conflict.

Religious conflict is especially deadly because the participants believe they are fighting for cosmic reasons—where death may be welcomed as martyrdom—and religious communities are the largest repositories of social capital in many civil societies, providing endless amounts of energy, people, and resources to mobilize.

But what if the social capital among religious communities could be bridged and people who orient around religion differently could be convinced to cooperate with one another? What if the cosmic narratives of religious traditions viewed people of other faiths as partners in the quest for the kingdom on earth? This is the hope of the interfaith movement, and building this movement is the job of interfaith leaders.

The Inaugural Prayer We Didn't Hear

An inaugural prayer should connect the particularities of one's own faith tradition with the pluralism of the nation.

WHO SHOULD BE able to pray at a presidential inauguration and what should that prayer be?

On Jan. 20, 1937, Monsignor John A. Ryan delivered the first inaugural benediction at the inauguration of Franklin D. Roosevelt with these words: "Almighty God, ruler of nations, we beseech thee to bless the people of the United States. Keep them at peace among themselves and in concord with all other peoples. Cause justice and charity to flourish among them, that they may all be enabled to live as persons created in thine own image and likeness."

Since this first benediction, ministers, priests, bishops, cardinals, and rabbis have offered prayers at the past 18 presidential inaugurations. Almost 76 years to the day since Father Ryan's benediction, Myrlie Evers-Williams became the first layperson to deliver the inaugural invocation, and Rev. Luis León, an Episcopal priest, offered his prayer for President Obama and our nation: "... with the blessing of your blessing, we will see that we are created in your image, whether brown, black, or white, male or female, first-generation immigrant American or daughter of the American Revolution, gay or straight, rich or poor ... with your blessing we will recognize the abundance of the gifts of this good land with which you have endowed this nation."

You may remember that the selection of Rev. León, like most decisions made in Washington today, did not come without controversy and an onslaught of protests. León, who ministers at St. John's Church near the White House and is known for welcoming openly gay Christians, replaced the administration's first choice, Rev. Louie Giglio. Giglio withdrew from the ceremony after the surfacing of his controversial sermon from 20 years ago condemning gay relationships. Giglio's stance on the issue of gay marriage is in sharp contrast to the beliefs of Rev. León, whose parish will begin to bless same-sex partnerships and ordain transgender priests this summer.

Storytelling and Social Change

The stories we tell today are simply the next chapter in an overarching narrative of hope, justice, and pluralism.

PERHAPS NO FRAMEWORK has impacted my organization, Interfaith Youth Core, more than Marshall Ganz’s approach to public narrative (“leadership storytelling”), best articulated in his March 2009 Sojourners article “Why Stories Matter.” We use it in our trainings with college student interfaith leaders and recommend it in the workshops we do with university faculty. Most famously, it was employed by the 2008 Obama campaign.

Like all effective frameworks, there is both a visceral and a heady quality to what Ganz teaches. Stories are the way human beings understand and communicate our deepest values, Ganz says, and there are three major stories that leaders must tell. The first is the story of self. This is not a selfish activity, or even one just about self-understanding (although that is certainly a piece of it). It’s about interpreting to others your reasons for being engaged in a struggle. This helps them understand your involvement and, more important, gives them inspiration and language to get active themselves.

The second type of story is the story of us. Religions, races, ethnicities, and nations tell such stories brilliantly but often do it in a way that excludes—and makes enemies of—those outside the magic circle. The challenge for the 21st century leader is to tell a story of us that includes people of all backgrounds who are fighting for the same cause. Stories of us build community out of people who would otherwise be strangers.

What We Know About Muslims

It's frustrating to be constantly represented by violent thugs and to be asked to explain their actions.

AS I WRITE this, the top story on The New York Times website reads “Anti-American Protests Over Film Expand to More than a Dozen Countries.” The slideshow includes images of angry young men with their fists in the air and masks over their faces protesting on dusty streets filled with riot police and open fires. As if Americans’ view of Muslims was not dark enough.

The film in question is the 14-minute YouTube clip called Innocence of Muslims that portrays the Prophet Muhammad as a buffoonish clown and even a child molester. It was created and promoted by individuals with a long history of anti-Muslim activities, who were perfectly aware that it would provoke a small segment of Muslims around the world to violence. And it is now that violent response that is defining the Muslim world to many people—just as in the case of the attacks of 9/11 and the riots provoked by the Danish cartoons in 2005. As @TheBigPharoah said on Twitter: “The sad thing is that those who attack embassies are like hundreds, barely a thousand. Millions are tarnished by what they do though.”

It is impossible to overstate how frustrating it is to be constantly represented by violent thugs and to be asked to explain their actions. Here is the question one African-American seminary student I recently met asked me over email: “Why do so many Muslims ... become so enraged when someone from the West deliberately breaks an Islamic rule they take as offensive?”

The Vocation of Presence

Sometimes I fly through my schedule so fast that I zoom past the craft.

A FEW YEARS back, Sojourners editor-in-chief Jim Wallis and I did a talk together at Northwestern University. After the event, the line to see Jim was dozens of people long. They wanted him to sign their books, to offer encouragement on their new social justice projects, to meet their kids, to give pastoral advice on a problem they were having. Jim talked to each and every one of them, some for several minutes. It delayed our dinner by at least an hour.

As we were finally sitting down in the restaurant and tucking in to our salads, I asked Jim why he stayed for so long. Why not do what so many other public figures do—leave right after your part of the show is over?

“I am a preacher and a pastor,” he answered. “An important part of my vocation is spending loving time with individuals. The period right after a public talk is an excellent opportunity to do that.”

“Plus,” he added, with a twinkle in his eye, “listening to other people’s stories may be the best part of this work.”

I just hit the 10-year mark of running Interfaith Youth Core, and the 15-year point of my first involvement with interfaith work. I haven’t logged as many miles or given as many speeches as Jim, but my schedule tends in a similar direction. The image of him talking to all those young people after that event at Northwestern sticks in my mind every time I board an early flight or prepare for a day of workshops followed by a late-night keynote.

Sikhs and Sacred Ground

Imagine the terror.

You are in a temple, a safe, sacred place, preparing for a morning service. In the kitchen, you are busy cooking food for lunch, while others read scriptures and recite prayers. Friends begin to gather for the soon-to-start service.

At the front door, you smile at the next man who enters. He does not smile back. Instead, he greets you with hateful stare and bullets from his gun.

Such was the scene Sunday at a Sikh gurudwara in Oak Creek, Wis., just south of Milwaukee, where a gunman, Wade Michael Page, killed six and critically injured three others before being shot down by law enforcement agents.

As Page began his shooting spree, terrified worshippers sought shelter in bathrooms and prayer rooms. Rumors of a hostage situation surfaced, and those trapped inside asked loved ones outside not to text or call their cell phones, for fear that the phone ring might give away their hiding place.

The first police officer to arrive on the scene stopped to tend to a victim outside the gurudwara. He looked up to find the shooter pointing his gun directly at him, and then took several bullets to his upper body. He waved the next set of officers into the temple, encouraging them to help others even as he bled.

That magnanimity is a common theme among the stories of victims and survivors of the Wisconsin shootings. Amidst terror and confusion, Sikhs offered food and water to the growing crowd of police and news reporters outside the gurudwara as part of langar — the Sikh practice of feeding all visitors to the house of worship.