Da'Shawn Mosley is an editor and journalist in the Washington, D.C., metro area whose beats include the arts, LGBTQIA issues, race, and U.S. politics. He is also a fiction writer, poet, and essayist. Da'Shawn earned a B.A. in English Language and Literature from the University of Chicago, studied creative writing at the South Carolina Governor's School for the Arts and Humanities, and was featured in the PBS documentary Becoming an Artist. His fiction earned him the 2019 A Suite of One's Own: A Writer's Residency, awarded by Kiese Laymon, and he has been published in America magazine and The Adroit Journal.

Posts By This Author

How to Thrive in a Decade of Accelerating Change

Tom Sine and Dwight J. Friesen on their new book, ‘2020s Foresight.’

Tom Sine has served as a futures innovation consultant for various denominations and organizations and Dwight J. Friesen is associate professor of practical theology at the Seattle School of Theology and Psychology. They spoke with Sojourners associate editor Da’Shawn Mosley about their book 2020s Foresight.

Sojourners: What motivated you to write this book?

Tom Sine: Essentially, a desire to write a more compelling book on the changes we’re facing in this pandemic and recession. Churches rarely do forecasting. As a consequence, they’re not ready for the next crunch. They care about their people, but they’re not thinking, “What’s going to happen to them as the recession gets worse?”

Dwight J. Friesen: Our book intends to say, “Listen, we don’t have to be passive bystanders to whatever the new normal’s going to be.” We can be proactive.

In ‘Love Child's Hotbed,’ We Are the Organic Matter

Poet Nikky Finney seeks the flourishing of Black families in a time of violent decay.

FOR BLACK people in the U.S.—a collective from which lives are still stolen on a daily basis, as though the slave-boat travels of 1619 never ended but merely set course in new directions to the same destination—reclamation is essential. Perhaps our history motivated the poet Nikky Finney’s father to repurpose a phrase that long had a negative connotation into a moniker to give his daughter positive focus.

“My mother steeped us in the stories of Black history and my father named me ‘Love Child’ in order not to give anyone else the opportunity to distract me from what I had come to earth to be,” writes Finney, winner of the 2011 National Book Award for Poetry, in her newest collection, Love Child’s Hotbed of Occasional Poetry. “So be she.”

And so she is. About a month into quarantine 2020, Finney released perhaps the most history-and-affection-freighted book to be published this harrowing year. Love Child’s Hotbed cannot be read on a Kindle. Less a typical, slender publication of modern verse, and more a hefty coffee-table book of startling import, it brings to mind The Black Book, that historical anthology co-edited in 1974 by Toni Morrison, the eventual Nobel laureate in literature who was an editor at the publishing company Random House. A book that strove to contain the vast lives of Black people in the U.S.—their horrific experiences and their magnanimous achievements—The Black Book was a gift to the nation’s children and grandchildren of slaves (and even inspired one of the greatest novels of all time, Morrison’s Beloved). Likewise, in a time of immense death and thus plundering of families, Finney’s latest book is a blessing for a continuously undone but never destroyed people, reaching into the past to grasp hope and self-worth to sustain their future.

‘Good Lord Bird’ a Few Feathers Short

I don’t begrudge Ethan Hawke for wanting to play John Brown and producing this project. John Brown’s life was vast and exciting; his willingness to take up arms to defeat injustice mirrors conversations we still have in the church today about nonviolence.

HBO's Revolutionary Black Artists Shine

‘Lovecraft Country’ has monsters and dangers, but extends its scope to include the large realness of Black life.

EVERYTHING THAT THE devil stole, HBO’s giving back to me. That’s a sacrilegious statement, but sometimes that’s how I feel when I’m on my couch watching yet another show with a largely Black cast (and sometimes even crew) miraculously greenlit in a sea of Hollywood whiteness by the network titan that years ago gave us The Wire and made many of us notice the likes of Idris Elba.

For what seemed like eons to Black folks eager for visual confirmation that their lives mattered, Black characters on TV were mostly relegated to sidekick or background roles—and Black writers, directors, and showrunners were rare or entirely absent. But from Insecure to A Black Lady Sketch Show, Watchmen to I May Destroy You, HBO is perhaps the strongest ally for revolutionary Black artists and creators of color on and behind TV.

Sufjan Stevens’ Latest Hymns of Honesty

The album is titled The Ascension but, I’ve got to be honest, Sufjan Stevens’ latest masterwork has me feeling the lowest I’ve felt about this country since the start of quarantine.

Why Faith Communities Are an Organic Part of HIV/AIDS Care

For Jesse Milan Jr., helping diverse communities end the HIV epidemic is a matter of faith, hope, and love.

IN 1985, WHEN Jesse Milan Jr. was in his late 20s, no one from his Philadelphia church attended his partner’s funeral. Not because they refused, but because Milan didn’t invite them. Doing so would have required him to say what he felt uncomfortable sharing: He loved a man who had HIV. He is a man who has HIV.

“This is never going to happen to me again,” Milan vowed to himself at the funeral, regarding the loneliness he felt because he didn’t draw close his church family at one of the most painful moments of his life.

Milan is now the president and CEO of AIDS United, an organization fighting the HIV epidemic in the U.S. He is adamant that no one in the HIV community be isolated from the love and support they need. “People living with HIV,” said Milan, “have a longing to belong. A longing to be cared for and a longing to not be silent or secret.”

A lifelong Episcopalian, Milan grew up in a congregation in the Diocese of Kansas, following the example of his mother and father in serving their spiritual home and, in times of need, allowing their siblings in Christ to serve them. Milan kept this mutuality in mind when he enrolled at Princeton University and, struggling to transition from public school and homesick for his church, joined the Episcopal Church at Princeton. It was, Milan told Sojourners, “an anchor, a port to tap into on a regular basis whenever I needed it.”

Helping communities live

FOR MANY PEOPLE today, the closest we get to understanding the impact of HIV/AIDS in the 1980s and early ’90s is through stage and screen portrayals such as Pose, Angels in America, and Rent. For others, the memories and losses of that time are vivid and unforgettable.

For instance, Jesse Peel, a gay psychiatrist and community organizer, documented in his journals the avoidance and terror of HIV that overtook his home city, Atlanta, and the nation. As many people rapidly contracted and died of the disease, doctors struggled to understand what was happening and many nurses refused to bring meals into the hospital rooms of the stricken, Peel wrote in documents he donated to a collection at Emory University. By 1994, AIDS was the leading cause of death for Americans age 25 to 44. It killed more than 350,000 people in the country between 1981 and 1995.

“I think the experience of people who are of a certain age will always be colored by our experience of the death and the dying,” said Milan. “Today, I sense that [younger] people’s commitment to HIV/AIDS work is more about the rights and the inequalities that are manifested in HIV and AIDS. They have a broad lens about where human rights need to advance, and that broad lens includes the trans community and all others.”

In the early years of the epidemic, many pastors and religious people publicly denounced and turned their backs on HIV-positive people. Others embraced those who were suffering, opening care programs and advocating for government funding. Reminding the nation’s leaders of their responsibility to the HIV community is a job that’s been done by many Christians and is a significant part of AIDS United’s history and present work.

A Black, Female Pastor in 'The Amen Corner' Takes Center Stage

When’s the last time you saw a play in which the main character was a black woman? If you’ve never seen one, you’re likely not alone. Although it’s the year 2020, and within the past year Slave Play and American Son were on Broadway, the number of American plays with black women as their leads staged in America still has immense room for improvement. As of today, zero are slated to appear on Broadway during the rest of the 2019-2020 season and the entirety of the 2020-2021 season. That’s why it’s shocking that, 55 years ago, The Amen Corner, a three-act play about a black woman pastoring a Pentecostal church in Harlem, N.Y., opened on Broadway, albeit more than a decade after its birth.

Let Black Voters Be Black Voters

Black churchgoers aren’t tools—or scapegoats.

FROM THE SOUTH CAROLINA Democratic primary onward, the votes for the presidency cast by black churchgoers will be criticized by many white people. Even now, black churchgoers’ feelings are speculated about in the press, like in-progress crimes announced on a police scanner.

Media and election pundits ask: “Are they going to choose Joe Biden because of his relationship with Barack Obama? Are they going to go for Elizabeth Warren because of her plan to give $50 billion to historically black colleges and universities and other minority-serving institutions? Are they going to bypass Pete Buttigieg because he’s gay?”

The latter question is the most problematic—an attempt to deem all black churchgoers as homophobic, as if homophobia is something no other racial, ethnic, or religious group has played a part in; as if there’s no such thing as the black grandfather who accepts his gay grandson; the black grandmother who always asks how her grandson’s boyfriend is doing; or the black grandmother who puts on her “good wig” to hang out with said boyfriend when he visits the South. All three are my Christian grandparents, and they’re not alone.

But the most problematic aspect of the Buttigieg question is what it reveals about white sight: Black churchgoers of the electorate are seen as tools to bring about a desired election result, and scapegoats if the election doesn’t go the white way.

Playing With Fire

A conversation with Robert W. Lee IV, author of 'A Sin By Any Other Name: Reckoning With Racism and the Heritage of the South'

Da’Shawn Mosley: What inspired this book?

Robert W. Lee IV: I’m a pastor first. But the events in Charlottesville, and our nation’s response, terrified me and inspired me to put pen to paper and say, “We gotta talk about this, because if we don’t, our silence becomes complicity.”

This summer marks the second anniversary of the white supremacy violence in Charlottesville. What is your read of where we are as a nation? Charlottesville will live in our collective history as an event of great horror. It was domestic terrorism. As we move forward, especially in the 2020 election, we’re going to have to talk about the deep chasm of racism that exists in our country without using it as a pandering mechanism to get votes. It’s important for us to care and be deeply concerned about these issues.

As a white man, how have you navigated wanting to be an ally and not be at the forefront of the movement while at the same time being catapulted into the public spotlight? It’s a learning experience. I hate to put it like that, but it is.

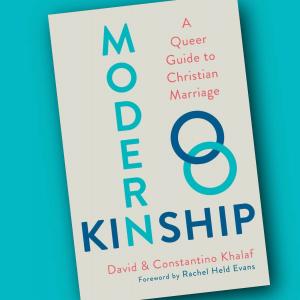

What God Has Joined Together

A review of ‘Modern Kinship: A Queer Guide to Christian Marriage,’ by David and Constantino Khalaf.

THE CHURCH THAT baptized me and was my spiritual home does not provide marriage counseling to LGBTQ couples. I doubt it even allows openly LGBTQ people to join its congregation. This treatment isn’t unusual: For years, many LGBTQ people have been denied true belonging and dignity in church bodies worldwide. Their romantic partnerships have been damned by clergy and discredited by loved ones. While heterosexual couples have been given pastors’ blessings and guidance, many LGBTQ couples have been abandoned to the harshness of life’s challenges.

David and Constantino Khalaf know this struggle well and don’t want queer Christians interested in finding a partner to have to figure out the complexities of faith, marriage, and commitment on their own. That’s why they have bravely written the book Modern Kinship: A Queer Guide to Christian Marriage.

Father Ted Hesburgh's Revolutionary Kindness

A Q&A with Filmmaker Patrick Creadon

The new documentary Hesburgh, which premieres nationwide on Friday, May 3, and is directed by the Emmy-nominated filmmaker Patrick Creadon (Wordplay, I.O.U.S.A.) gives us a thorough look at Father Hesburgh’s walk. From Hesburgh’s origins to his decision to devote his life to the priesthood, to his appointment — at the young age of 35 — as president of the University of Notre Dame, to all the personal, national, and global adversities that the man of the cloth later faced afterward, Hesburgh weaves a beautiful and engaging story of faith lived out.

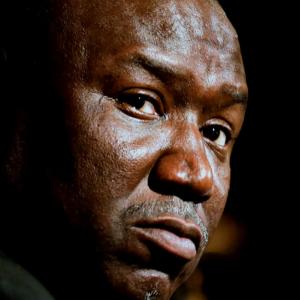

The Advocate

The stubborn faith of the civil rights attorney who represented Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, and many others.

IF I WERE MURDERED TODAY—say, shot and killed while walking unarmed through a residential area, wearing my hoodie—and my murderer weren’t arrested by dawn, my family would make one phone call. To Benjamin Crump.

This has become the African-American family emergency plan—set in motion when the “hurricane” is a white person with a gun. Call Benjamin Crump.

This is what Trayvon Martin’s family did in 2012 when they realized the criminal justice system would not punish the man who killed Trayvon. They called the lawyer who once stood on the steps of a courthouse where two white men had just been acquitted of beating to death a 14-year-old boy and said: “You kill a dog, you go to jail. You kill a little black boy, and nothing happens.” They called the attorney who, time and time again, tries to make something happen. They called Benjamin Crump.

In Trayvon’s case, Crump, one of the best-known civil rights attorneys practicing today, thought at first that something would happen without his help—since the only thing Martin had in his possession when George Zimmerman shot and killed him was a can of fruit juice and a bag of Skittles. When Crump realized there was a strong possibility that justice would not be served, he came face-to-face with what he calls “a test from God.”

“Nobody was watching this call between me and this brokenhearted father, save God,” Crump told Sojourners in a phone interview in October. “And I believe God was testing me to see if I was going to answer the bell, use the blessings and education and all the other things [God] has given me to be a blessing to the least of these. I stepped out on faith to do the right thing. And God took over from there.”

Can This Planet Be Saved?

‘Behold the Earth’ is a film on faith in a time of climate crisis.

IN OCTOBER, The New York Times published an article that, despite its dire implications, seemed to wash away in the rapid news cycle. It described how, according to the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the world’s population will see major consequences, as early as 2040, from its mistreatment of the planet. More droughts, more wildfires, more poverty, and higher temperatures—in only 22 years. When that time comes, when nature begins to resemble Hell, how will we have to live?

Emmy-nominated documentary filmmaker David Conover has been thinking about this question for 12 years. “I was a parent of two young kids,” Conover told me about the moment when he began to ruminate on creation care, “and was trying to understand the world they were growing into: pollution, severe weather with fires, flooding, droughts, struggles with realities that weren’t that apparent even a generation ago.

“There have been many films made about those things, how we know that they’re happening, what’s causing them, and so on. But there haven’t been any films about people and their experience of exploring the very tough question of how to live right today in this climate.”

Conover’s wrestling with how to live a moral life during a time of environmental hardship has culminated in the production and release of his newest documentary, Behold the Earth, which explores contemporary Christianity’s relationship with creation care.

Recentering Spirituality for People of Color

How the Mystic Soul Project is creating a space for activism, mysticism, and healing for people on the margins.

WHEN TERESA P. MATEUS attended gatherings on Christian contemplative spirituality, she often didn’t see herself reflected in the spiritual practices “centered in whiteness” that she found emphasized there. She yearned for spiritual resources that drew on the experiences of people of color—and out of that yearning, the Mystic Soul Project was born.

Mateus is a graduate of the New York University School of Clinical Social Work and the Living School at the Center for Action and Contemplation and author (under the name Teresa B. Pasquale) of two books on recovery after trauma, including Sacred Wounds: A Path to Healing from Spiritual Trauma. Da’Shawn Mosley, assistant editor of Sojourners, spoke with Mateus in August about how the Mystic Soul Project brings healing and spiritual nourishment to people on the margins.

Da’Shawn Mosley: Tell us about the Mystic Soul Project.

Teresa P. Mateus: Our basic mission is activism, mysticism, and healing centered around the life experiences of people of color. We create space for conversations, relationship building, practices, and other programming that have a people-of-color perspective and allow many to reclaim ancestral practices that have been abandoned or erased by Western traditions.

From State Government to Kavanaugh: Filmmaker Kimberly Reed Investigates ‘Dark Money’

From the start of his bid for the Oval Office to now, the 45th president of the United States has drawn plenty of accusations of illegal activity for his finances and the funds of his companies. Many of us have paid close attention to the developments of investigations into this money, watching cable news and following journalists we trust on Twitter. But perhaps we should also turn our attention to other areas of our government, look beyond the executive branch to search for signs of money and politics intermingling in nefarious ways.

In the Mourning

A poem.

This mourning begins with eyes:

ours which open

and the eyes a gun closed,

the barrel a chamber in which there is found no heart,

for every latch and mechanism of the machine moves with menace

and every finger entangled and wound around its trigger

draws closed the stage curtains of peace.

This mourning begins with flesh—

our stance under a persistent sun

as a body stretches across a coroner’s table like the hide of a deer.

In such an occasion, a body’s bullet holes

become mouths. They speak of the perils our muscles

hope not to know. They reveal what it’s like

to be whole and come undone

and linger like litter.

Parkland.

Pulse.

Emanuel.

Columbine.

For you, we combine this mourning

with the mournings that have become before it.

How to Be a Bystander

Four questions for Gail Hyder Wiley.

Bio: Gail Hyder Wiley is the organizer of Charlottesville Gathers, a group in Charlottesville, Va., that has taught hundreds of people nonviolent active bystander tactics and encourages resistance against racism, especially resistance led by people of color.

What inspired Charlottesville Gathers to organize nonviolent active bystander training? I saw what was happening after the election—that people were getting assaulted and demeaned, and it was just turning into a dangerous place for people who are outside of the spectrum of white privilege. There were a lot of people in December 2016 talking about the resistance, but there didn’t seem to be much training going on. I was impressed by the stories of people who used church basements, during the civil rights movement, to teach people nonviolent civil disobedience. I thought, “Okay, I belong to a church that has this big library, and it sits idle some nights, so why don’t we use that and bring in people who can help the community learn how to grapple with what we’re dealing with.”

What acts of racism have occurred in Charlottesville since last summer? There has been a string of incidents of white supremacists targeting our community that hasn’t made the news: white supremacist stickers placed over the new road sign for “Heather Heyer Way,” an activist’s tires getting slashed, and countless more insults and threats. Our immigrant neighbors have been fearful as the policies of our current president have become apparent, and the violence of the white supremacists in our area has amplified that fear.

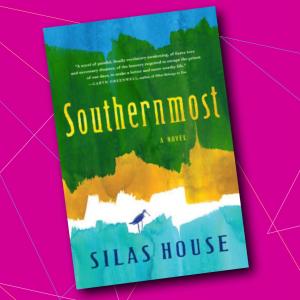

A Flood of Wonder

Southernmost, by Silas House. Algonquin Books.

TO BE A FATHER is to be an example, and the writer Silas House knows this well. His latest novel, Southernmost, is the story of a father and pastor named Asher who strives to do what’s right, while his young son, Justin—who is distrustful of the church—watches.

But Asher’s quest for morality places him on a path of unwanted attention and threatens to separate him from Justin, until Asher makes the questionable decision to take his son with him on a journey for which neither of them are prepared.

Rarely have the church’s tensions about homosexuality—and how deeply those tensions can fracture a family—been explored in fiction. But with this, his sixth novel, House explores how Asher’s relationship with his wife, Lydia, disintegrates when, to Asher’s disgust, she turns away a gay couple in need of shelter after a flood. House examines Asher’s heart, which is broken over his failure to defend his brother Luke when they were young, forcing Luke to go it alone in dealing with societal hatred over his sexual orientation. In Asher’s heart, House finds hope and desire for a faith that welcomes more than it excludes.

Our 2018 Movement Honorees

Sojourners honors five leaders who are working to make our world a more just and peaceful place.

MANY PEOPLE TALK about the injustices in the world but do nothing to rectify them. This can’t be said about the following five leaders—pastors, activists, lawyers, businesspeople, and artists—who Sojourners will recognize as “movement honorees” at the June 13-15 Summit 2018. These innovators are doing what Jesus did: taking God’s vision of the world and spurring others toward that ideal. Rev. Brittany Caine-Conley

Rev. Brittany Caine-Conley

“I learned pretty early about myself,” Caine-Conley told Sojourners, “that the concepts of justice and righteousness were really important concepts to me.”

Cue Aug. 12, 2017. While much of the nation watched from afar the racially charged violence in Charlottesville, Caine-Conley encountered the physical threats in person as she protested the white nationalist rally in her city. Caine-Conley and other protesters were shoved by supporters of the Unite the Right rally. And the car that a Nazi sympathizer plowed—apparently on purpose—into a crowd of protesters, killing 32-year-old Heather Heyer, also injured an affiliate of Congregate Charlottesville, the local faith-based social justice network Caine-Conley, United Church of Christ minister, helped organize.

“It was the most horrible thing I’ve ever experienced,” Caine-Conley said to Vox about seeing the wounded, who were lying in the street in the car’s wake.

And yet Caine-Conley believes it is her duty to be wherever tragedies like this happen—to put herself in harm’s way.

Love on Wheels

Four questions for a pastor who started a mobile tiny house project.

Bio: Bruce Schoup was pastor of Peace Congregational United Church of Christ in Clemson, S.C., when the church started a new outreach project. The goal: Build a mobile “tiny house” to serve as temporary residence for LGBTQ people kicked out of their homes due to their gender and sexual identities. Nationally, 40 percent of homeless youth identify as LGBTQ.

Website: thepeacechurch.org/tiny-house-project