Oct 21, 2021

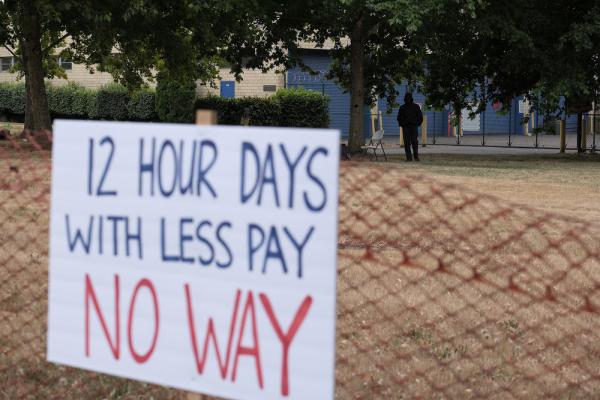

The latest headlines are filled with news of worker shortages, delayed supply chains, and labor strikes. Cornell University’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations strike tracker reports more than 181 strikes so far this year, with 38 of them taking place in the first two weeks of October, spurring the AFL-CIO to name this month “Striketober.” These strikes span all kinds of industries, from hospital workers to whisky makers.

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login