For Saffet Abid Catovic, being kind to the environment is an act of faith. It respects the example set by the Prophet Mohammad and those before him, Abraham and Ishmael, who, it is said, strove to find balance between humans and nature. So it seems fitting that Catovic and his family made a personal commitment to ensure that their first pilgrimage to Mecca — also called the Hajj — was a sustainable one.

“We need to follow in the footsteps of their eco-conscious practices — although they weren’t called that at the time — so that their experiences performing the rituals and interacting with the natural world might make for an accepted, blessed and complete Hajj,” Catovic said. “The rocks, the plants — they are for the service of God, and we are here for the service of God. The entire earth is a place of prayer. We keep it clean. We keep it non-polluted. That service cannot be done by harming God’s house of worship.”

The journey to Mecca is one of the five pillars of Islam, which also include faith, prayer, charitable giving, and fasting during Ramadan, and are the tenets every observant Muslim lives by. Everyone who practices Islam — and is able — is expected to make the Hajj at least once in a lifetime.

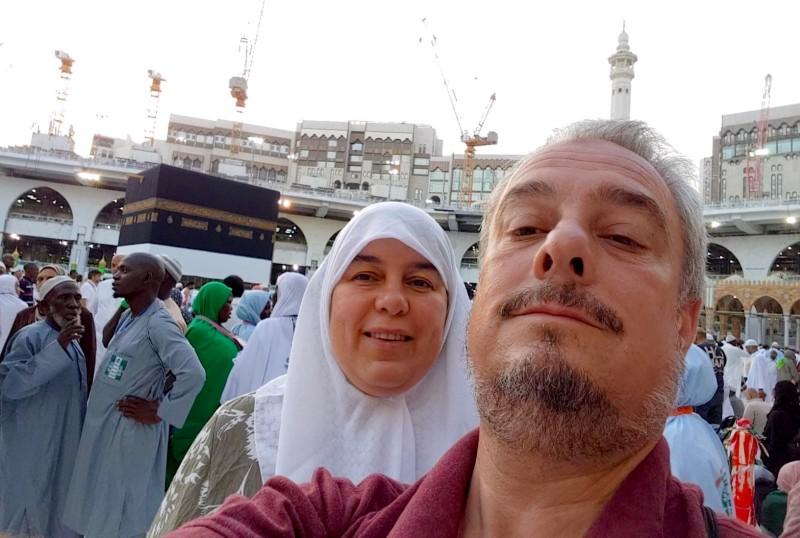

“The Hajj, at its essence, is a gathering of the global Muslim community answering the call from God to come together to work collectively,” Catovic said. “Everybody is working individually and they are at the same time one collective. For example, one of the rituals we do is going around the Ka’aba [in Arabic, ‘the cube,’ an ancient stone structure at the center of Islam’s most important mosque]. Each of us does this individually, but we also do it as a collective. This mirrors the effect of working locally to effect change globally.”

Recently, more than 2 million Muslims from around the world made the five-day pilgrimage to Mecca, a city in western Saudi Arabia that is Islam’s holiest site. Many of them got a firsthand taste of climate change, as uncommonly heavy rains deluged Mecca during the Hajj’s early days, raising the risk of flooding.

“Temperatures are rising, and I’m a believer in the scientific facts that demonstrate climate change is real,” Catovic said. “It is critical that we address these challenges directly, especially in the Middle East and in those lands that center around the Equator, many of which are Muslim majority lands, and many of which are already facing the most intense effects of climate change.”

1_ttx4jh9rd2l8djug4g326w.jpeg

Catovic, 53, is an American Muslim of Bosnian-Anglo descent who lives in New Jersey and serves as the senior Islamic advisor to GreenFaith, an interfaith coalition for environmental issues. He believes the responsibility of fighting climate change begins with the individual, but stresses that the Green Hajj is “not just about the more privileged parts of the Western World. I am just one person who is making this commitment. There are many other millions of people who are doing this too.”

Catovic said he was inspired by a meeting with a family who came from Afghanistan, traveling over land by donkey, then by boat, and finally walking. “Whether they are traveling in these ways by choice or by necessity, they certainly have a lower carbon footprint than my family,” he said. “In some ways, they are getting it right and following the example of the Prophet Mohammad — blessings be upon him — more closely.”

But Catovic, his wife, son, and daughter-in-law, made a serious effort to shrink their carbon footprint during this trip, starting with transportation. It’s hard to lower the toll of airline travel, especially flying from the United States to Saudi Arabia. So they offset it by donating to a project in Panama that replants trees and promotes fair wages within the lumber industry.

Once in Mecca, they walked as much as possible. “A lot of the rites that must be done can be done by walking,” he said. “Even when the Prophet Mohammad had the opportunity to ride a camel, he would choose to walk. So we are choosing to walk whenever we are able.”

Their hotel is only about a third of a mile from the entrance to the sanctuary, where many of the rites occur — easily walkable. “Saudi Arabia also has a great bus system that transports folks from the local airport to Mecca, but these are unfortunately gas vehicles,” he said. “That said, they do a good job of making sure that all the buses are packed fully.”

It also is a tradition to travel to Medina after the rituals in Mecca, following in the steps of the Prophet, a journey of about 300 miles. “Many Muslims do this, although it is not an official part of the Hajj,” he said. “We will be traveling by bus and have figured that into our carbon footprint calculation that we have offset.”

They also abandoned the hotel buffet for a diet consisting mostly of dates. Dates are locally grown and require no processing, refrigeration or long-distance shipping. Also, aside from the pits, they create no waste.

“Medina is known as ‘The City of Dates’ and has about 20–30 different varieties of dates that have been grown in this region for thousands of years,” Catovic said. “Ramadan is traditionally broken by eating dates, and Muslims around the world know that the Prophet ate dates. This is another practice that connects the different acts of worship.”

In terms of the Wudu, the ritual purification with water three times per day, “we use no more than what amounts to two cups of water,” he said. “This is something that needs to be reinforced here, especially for folks who are staying at the nice hotels that do not limit any amount of water you can consume. These folks should think about the model of the Prophet Mohammad, and that means consuming less water.”

Systematic implementation of the Green Hajj idea, “is not yet there,” he said. “The general principles and guidelines are available around the world, but there is still a lot of work that has to be done.” He hopes that his personal story — and that of others — trying to make the Hajj environmentally sensitive will inspire more Muslims to do the same. “Individuals are part of the problem, but we are also part of the solutions,” he said.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!