I looked at the clock. It was 3:30 a.m. — the early morning hours of Nov. 9. Donald Trump stepped to the podium and shared with the audience that he had just received a phone call from Hillary Clinton conceding the 2016 election. He won.

As he rose to the podium, my stomach shook. Then my shoulders, then arms. Clenched hands released and stretched wide as deep cries rose from my marrow. That’s what it felt like — my marrow cried — then wailed with a primal scream. My whole body screamed because it felt like permission to thrive was being ripped from my black female body.

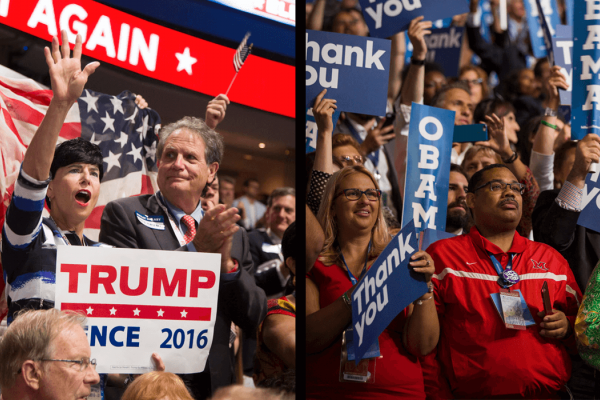

Even as I sat shaking in my living room, men and women in red baseball caps across the televised ballroom — and across the country — raised hands in victory. Many of them were white evangelicals.

How could this be, I thought. How could the responses of people from the same professed faith be so categorically different? How could we look on the story of the past and choose such different stories for the future of our nation?

Here’s how: We have been living according to different stories of America’s past. As a result, we interpret the present differently. In turn, we dream a different future.

In 1999, I visited a major evangelical university to speak for a freshman writing class. The class assignment was to write about the topic of my lecture. I spoke on the story of the Good Samaritan. In the course of a one-hour talk, I mentioned the word “slavery” once. I shared how I’d reached a new depth of commitment, intimacy, and connection with my white friend when we realized that some of our conflict was due to brokenness passed down through the generations from slavery to present. Now it was affecting the health of our relationship.

My talk closed with a charge to heed Jesus’ call to love without limits — to love everyone — to love with extravagant love.

As the professor opened the time of Q and A, the first hand shot up.

A young white man crinkled his brow, leaned back in his chair, and said: “What does slavery have to do with anything?”

“I’m sorry?” I asked.

“What does slavery have to do with anything?” he shot back. “It only lasted for about 50 years. It wasn’t that long. Why can’t you people just get over it?”

To be clear, the legal enslavement of people of African descent on American soil took place over the course of 246 years, from 1619 in Jamestown, Va., to the 1865 passage of the 13th Amendment.

How could this young white man believe that slavery only lasted 50 years? I asked him.

“The country was only about 50 years old when the Civil War happened,” he said.

Never mind the fact that the fledgling nation was 89 years old and the fact that all of the same courts and colonial leaders were in place before and after the Revolutionary War. It was their laws and judicial rulings that enslaved black people before and after the revolution. Never mind the fact that black men and women were not suddenly enslaved in 1776 after thriving on this land before. We had languished under the lash of the whip for 160 years before the declaration that all men are created equal.

What is it in our understandings of the stories of our world, the story of Jesus, and the stories of our lives on common land that leads us to such disparate understandings of the past and present? I believe the answer lies in the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves and our world.

I write this reflection from Cape Town, South Africa — home of the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission. The TRC revealed the hidden stories and repercussions of apartheid-era oppression. The nation can never doubt again what exactly happened. The perpetrators’ confessed violent attacks against the image of God in black and “colored” corners of their nation is in the permanent record.

The U.S. never had its truth commission.

Few detailed stories have risen to the surface from the mouths of both the enslaved and slave owners to reveal what exactly happened. Our history books were written by former oppressors. They call the enslaved “undocumented workers” and “immigrants,” warping present-day perceptions of reality. They dedicate one page or one chapter to the topic of slavery, then rehearse founding U.S. presidents with no reference to the fact that they too were slave owners.

It is often said the distance between racial groups in the U.S. is great. That is true. But I have come to believe the actual distance between us is only a reflection of the distance between our stories.

How might the possibility of repair rise if we all took in the stories of us? I want to believe my body and spirit could find peace once again.

Interested in more content like this? This article is part of our Faith in Action Newsletter. FIA is a monthly compilation of articles that empower people of faith to draw from a deep well and boldly advocate for a more just world. Subscribers receive monthly resources for prophetic preaching, practical insights for organizing, and reflections on spiritual leadership delivered to their e-mail. Subscribe here.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!