Nov 22, 2019

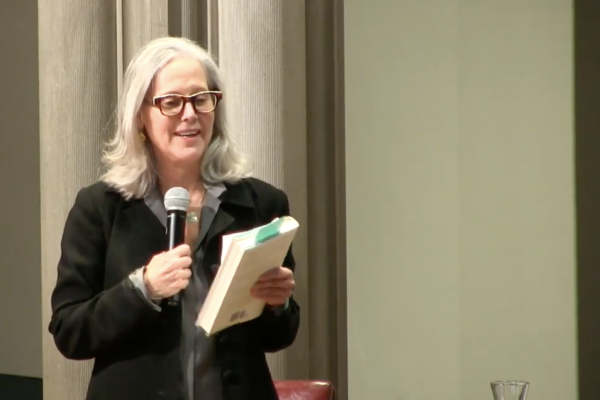

Dr. Serene Jones serves currently as president of the historic Union Theological Seminary in the City of New York — the first woman president in the institution’s 183 years of existence. Among her many illustrious achievements, Jones also served as president for the American Academy of Religion, the world’s largest association of scholars in the field of religious studies. Jones grew up in Oklahoma with her family, which she describes as “progressive and deeply Christian.”

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login