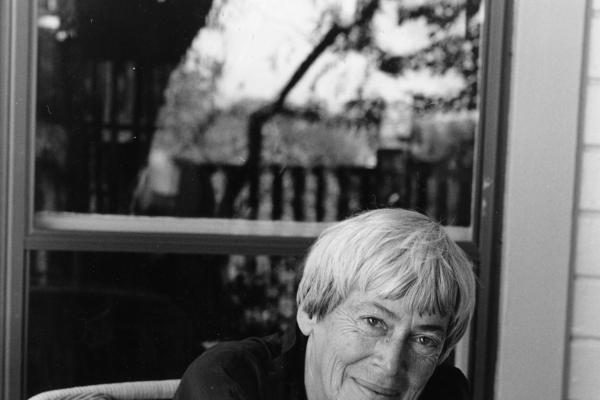

Le Guin, an American fantasy and science fiction novelist who has also authored numerous short stories, essays, and children’s books, died at age 88 on Monday. I will admit, my love for science and fantasy fiction is relatively new. But my theological imagination is indebted to her work.

Le Guins’s award-winning novel published in 1969, The Left Hand of Darkness, explores the theme of loyalty and betrayal. It follows the adventure of an envoy, Genly Ai, who seeks to establish a connection with people (Gethenians) from a cold planet that has never seen war, and where there is no gender. An essential component to Le Guin’s narrative is that we navigate this planet through the eyes of a character for whom the concept of ambisexuality is also foreign. Ai struggles to decipher his encounters with others outside a context of gender: We watch him attempt to mentally process physical attributes, personality traits, and behavior he has conditionally associated only a feminine or masculine, here encountering them all within a single individual.

Another slice of the novel takes on the perspective of a female explorer, Ong Tot Oppong, a preliminary Investigator visiting Winter. Oppong describes her resignation to the use of “he/his/him” in her thoughts, noting that it prevents her from fully grasping the nature of a Gethenian, who is neither man nor woman, “but a manwoman.”

These field notes of a fictional ethnographer on an imagined planet touch on a truth: As a woman who was conditioned to see God as father, my role as a Christian was shaped by the nature of a father relationship. And while this may not inherently be harmful, it is limiting. In The Left Hand of Darkness, I was invited to step into and imagine a world where gender was not a burden, privilege, or factor — for me, or for God.

What is it like for a man to pray to God the Father, all the while knowing he could be a dad himself one day? What is it like for a boy to hear stories about the twelve disciples and be able to picture himself as one of the few whose following of Jesus is captured as a leading role in Scripture? When I imagine these scenes as a woman, is there a sense of intimacy or likeness I am missing?

Through The Left Hand of Darkness, Le Guin crafted a world in which a “division of humanity into strong and weak halves, protective/protected, dominant/submissive, owner/chattel, active/passive” — ever present in our own culture, too — is missing.

Her subversive writing bolsters the challenge that egalitarian theology poses to the authority of tradition. If relationships are a way to better understand God, I find it sad that we often confine our connection with God to a single dynamic. Since The Left Hand of Darkness, I have become more creative with my prayers, petitioning to God as my sister, mother, friend, among other things — not because these roles are a more accurate depiction of who God is, but because these relationships help me better understand all the different ways God loves and cares for me.

When writing The Left Hand of Darkness, Le Guin said she “eliminated gender to find out what is left.” Perhaps we might apply this same thought experiment to church, to religion, and who we understand God to be. What remains?

Le Guin writes:

“Fiction writers, at least in their braver moments, do desire the truth: to know it, speak it, serve it. But they go about it in a peculiar and devious way, which consists in inventing persons, places, and events which never did and never will exist or occur, and telling about these fictions in detail and at length and with a great deal of emotion, and then when they are done writing down this pack of lies, they say, There! That’s the truth!”

As I mourn Ursula Le Guin’s death, I celebrate her work. I celebrate the questions she asked, as well as the ones she led me to. I celebrate her devious and idiosyncratic thought experiments, and her encouragement that “the truth is a matter of the imagination.” I celebrate her poignant and subversive philosophy, and the waves she created in the literary community.

Science fiction invites readers to suspend their understanding of reality and re-imagine it within the context of another time, place, and people, ultimately serving as an introspective mirror to our own humanity. Fiction is less about escapism or being buried under a grandiose lies, but rather digging into and courageously uncovering a deeper sense of self.

For this awakening, I thank Ursula K. Le Guin.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!