Nov 10, 2017

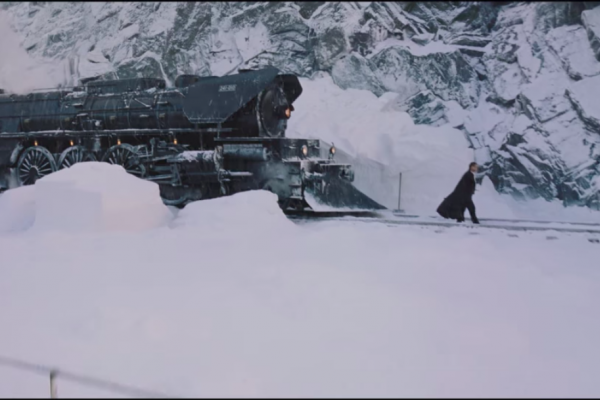

Kenneth Branagh’s new big-screen adaptation of Christie’s novel is a diverting, gorgeous-looking film that struggles a little at showing the humbling effect that dilemma has on the great detective. However, it does a good job of portraying the pain at the center of this story, and how it metastasizes in its characters.

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login