Oct 28, 2020

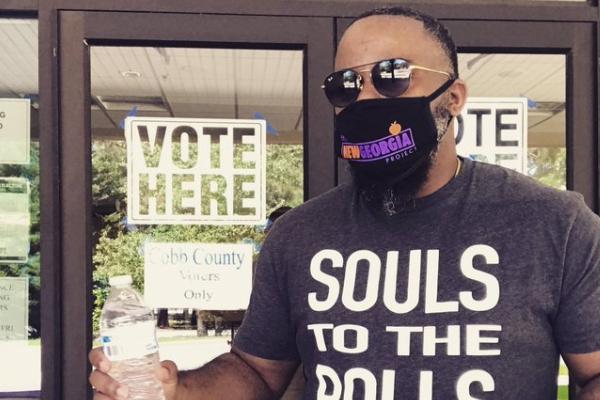

“Nine times out of 10, we’ll just be greeting people and passing out water and snacks,” said Billy Michael Honor, who directs Loose the Chains, the faith engagement initiative of The New Georgia Project “But in the event that something does happen, it’s good to have people there who know how to lead people in situations of conflict or crisis.”

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login