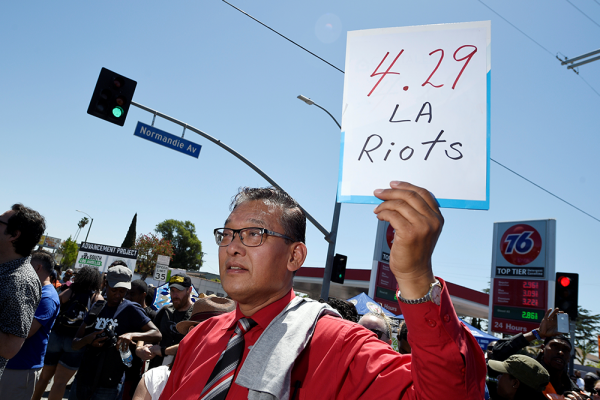

Apr 28, 2022

The devastation of the 1992 riots inspired Hyepin Im to advocate for the economic and political empowerment of underserved communities, including Korean Americans — and her own faith led her to look for ways that churches could be more effective partners in this work.

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login