welcoming the stranger

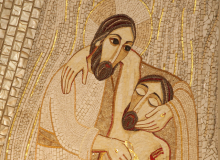

“I didn't come here because I wanted a job ... I came here because I wanted to live.” These words from an undocumented immigrant came early on in Church World Service's Summit on Immigration Reform in Washington, D.C. They could have easily been the words of Mary, mother of Jesus, as they fled to Egypt during his childhood.

“We just wanted to live.”

The reality is, as Christians, our tradition, our faith, our roots, are all tied up in an immigrant identity – or at least they should be. Reaching as far back as Adam and Eve, and Abraham and Sarah, we are a people who are on the move. We are typically found in places other than where we began. Even parts of the texts we use to guide us on our journey to/toward/with God were put together as the Israelites were living in a foreign land.

As Christians, we must recognize that we are truly a people with immigrant roots which reach all the way back to our Jewish spiritual ancestors. In that recognition, we need to learn to fully embrace the call of Deuteronomy to show hospitality to sojourners. It's a call that is about so much more than being welcoming and offering drink and food (although it does include those). The “hospitality” we are called to is one of seeing someone whom we may identify as “other” and loving them.

I'd make the argument that in his teachings, Jesus takes that concept a step further and tells us we shouldn't see them as other, we should see them as yet another image of God – another opportunity, another invitation, to not only share God's love but to know it more fully.

What kind of tentmakers are we? Are we more like Martha, so preoccupied with busywork that we neglect our neighbors, the guests of honor? Do we stand by and rejoice in the misfortune of others suffer the consequences of their own doing, rather than inviting them in and making room for them at the table, under the protection of our shade? When we see a stranger come by, do we drop everything, bring out the best of what we have and sit at their feet in humble service?

In recent weeks, a number of controversial and divisive political questions have dominated the news. Race and voting rights, abortion in Texas, and marriage equality at the Supreme Court have opened anew the scars of old political and cultural wars.

In this conflicted political ambit, the Samaritan's bold compassion is a needed reminder today. Let’s remember to be kind to the stranger, certainly. But just as important is that the story of the Good Samaritan also invites us to imagine ourselves in a different part of this narrative.

Imagine yourself not as the Samaritan seeking to love God and neighbor. Imagine yourself as the person in need. A man on the brink of death. A woman in deepest grief. A man lost in the world. A woman with no hope. Imagine yourself at your most vulnerable, deep in despair with only one hope: perhaps someone will help me.

We had taught, run, and dreamed together. Our ministries were growing, I was once again flourishing spiritually, but Richard seemed to be stalled. His peers were finishing college, finding jobs and mates, and Richard was hustling to find odd jobs and was being left behind. As we tended the land, I took a risk. I asked him why he had said he did not want a family. He confessed that he had reached that conclusion out of despair. He truly wanted to find a wife and previously hoped to have kids, but he did not have citizenship (his family moved to the U.S. when he was 7 years old) and was not able to find legal, reliable employment. He could not afford to go to college without access to financial aid. He insisted he simply would not start a family that he could not reliably provide for. He had lost hope. But he still had integrity. I was deeply saddened. I was saddened for Richard and his loss of hope. I was also saddened that our community and nation would potentially be deprived of his vision and courage.

The momentum for immigration reform is building across the country, but leaders in Washington are often the last to realize the seismic shifts taking place. The most recent example is when Alabama Sen. Jeff Sessions made the claim that there is no “moral or legal responsibility to reward somebody who entered the country [without documentation].”

No moral responsibility? Many Christians believe otherwise.

Charity doesn’t leave us unchanged, which is just one reason why it’s hard to make ourselves do it.

To be more specific: when we extend generosity and justice to others, it alters our relationship to them. Especially when those “others” are foreign to us. Hospitality has ways of making the people who receive it come inside and stick around, whether we really want them to or not.

We see this on display in Luke 4:22-30, which tells the second half of a story about Jesus’ statements to a group assembled in his hometown synagogue, in Nazareth.

The story began, in Luke 4:16-21, with Jesus unveiling his mission statement: he says he intends to be God’s instrument for releasing people from oppression of all kinds — spiritual, economic, political, physical, and social. This is the first narrated episode of Jesus’ public ministry in Luke’s Gospel, and so it lays a foundation for everything that follows. Summoning from ancient Israel’s scriptures grand themes about God-given justice and abundance, Jesus identifies himself as one determined to play a part in God’s intentions to free humanity from its sufferings.

At the corner grocery in our Jabal al-Webdah neighborhood of Amman, a Syrian man in his early 20s now runs the meat and cheese counter. Ahmed (not his real name) is one of more than 150,000 Syrians who have fled to Jordan since his country’s violence began in March 2011.

Young males seeking to avoid mandatory military service are one of the largest groups leaving Syria.

Ahmed wires his wages to his family in Syria and calls them each evening to be sure they are still safe. “The situation inside Syria is even worse than reported in the news,” he laments.

A recent UNHCR report notes that, increasingly, Syrians are arriving in Jordan with only the clothes they are wearing and with few economic resources after months of unemployment.

Whenever possible, I plan my Saturday errands such that I’ll be able catch part of “This American Life” on public radio as I drive and I’ve often found myself sitting in the grocery store parking lot to hear the end of a story.

One recent Saturday, the show’s theme — which ties together each of its non-fiction stories — was the biblical truism that “you reap what you sow” (Galatians 6:7), and most of the program was dedicated to examining the consequences — intended and otherwise — of Alabama’s controversial, toughest-in-the-nation immigration law, HB 56, which passed last June.

Whether what is happening in Alabama as a result of this law — and, as the program reveals, a great deal is happening, even if most of us outside of the state aren’t paying attention — was the intention of the bill’s authors and supporters is not entirely clear. What is clear, from a Christian perspective, is that the effects are devastating.

What most saddened me in the program was the statement of a young undocumented woman named Gabriella that, since the passage of HB 56, she finds herself unwelcome everywhere. “Even in the church,” she says, “you find people that… don't want to talk at you. And they don't want to give the peace to you.”