seeing the image of god in others

Everett Historical / Shutterstock.com

THEY CAME TO the front and waited to speak with me. They were weeping.

The day before, I sat in the front seat of a packed car. Five beautiful black women, including one of the women now in tears, rolled toward Marion, Ind.—the site of the last public lynching in the North.

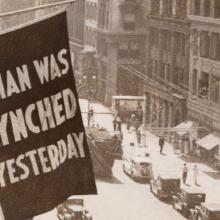

On the sweltering summer night of Aug. 7, 1930, three African-American teenagers—Thomas Shipp, Abram Smith, and James Cameron—sat huddled in their jail cells in Marion. Thousands of white men, women, and children gathered outside the jailhouse, screaming and jeering—demanding blood. The three were charged with the ultimate sin against whiteness—killing a white man and raping a white woman. They were dragged from the jailhouse, beaten, and strung up on a low-hanging tree branch a block away on the courthouse square, in the center of town. For some reason, Cameron was spared. The other two were not.

The town photographer captured the moment: The mob congregated like lions around mangled prey. Lips licked, satisfied grins splayed across the faces of young women and old women, young men and old men. Floral dresses, white shirts with buckled pants, and hats atop straight-backed heads covered bursting egos as they reveled in victory. One man pointed to their ritual sacrifice, and that moment became an iconic illustration of American lynching.

Sometimes we dehumanize people by speaking, thinking, or imagining about them in generalizations, by covering their true identity with generic labels and terms that are impersonal, cold, and less meaningful. For example, you can refer to your brother as “someone that I know” or your best friend as “this one guy.”

We often do this when we want to create separation or disassociate from others — often in order to protect ourselves, make ourselves look better, or attack others. Thus, we refer to our spouse as “this person I know” when we’re agreeing with a coworker about people who hold an opposing political belief we disagree with, or offhandedly use the phrase “this guy I know” about our dad when talking about annoying habits that we can’t stand.

We see Peter do the same thing in the Bible, referring to Jesus — his savior, closest friend, companion, teacher, and leader — as simply “him” when being accused of knowing Jesus right before the crucifixion.

Luke 22: 56-57: Then a servant girl, seeing him as he sat in the light and looking closely at him, said, “This man also was with him.” But he denied it, saying, “Woman, I do not know him.”

I don’t know “him.”

One word: him.

No harm done, right? It’s just a simple pronoun.

We do the same thing all of the time.

Him, her, she, he, them, those people, etc.

As innocent as this practice may seem, the ideas behind them are more cynical, and it becomes much more serious for Christians when we use terms, thoughts, and ideas as a way to disconnect people from God.