science and religion

ON A RECENT morning run, I saw a yard sign that began, “We believe ...” and included a list of creedal-like commitments. One stood out: “Science is real.”

Science? I thought. Does belief in science really need front-yard creedal affirmation?

One trend of the recent divisions in our nation is a heightened distrust in science among evangelicals and the Religious Right. This pattern has been acute during the COVID-19 pandemic, when research by epidemiologists and other members of the scientific community has been increasingly called into question by conservative pundits, political officials, and religious leaders. The costs of this rhetoric and its effects have grown far beyond alarming.

Where did this science and religion rift come from? And how can we speak into the fear and mistrust in the work of science that has taken root in recent years in a way that cultivates trust and encourages mutual concern?

The origins of this rift are not easy to trace, fed as they are by a variety of sources. Thomas Dixon, in the book Science and Religion: A Very Short Introduction, attributes the science-religion conflict narrative to three sources: Enlightenment rationalists in the late 1700s, Victorian “free-thinkers” in the mid-1800s, and modern-day scientific atheists at the end of the 1900s to the present. “Few things make thinking like a scientist more difficult than religion,” wrote Sam Harris, a prominent atheist, in The New York Times in 2009.

Great numbers of contemporary Christians have arrived at the opinion that their faith tenets and the work of science are in conflict, though this is far from a homogenous view. According to Pew Research Center analysis of data from the Wellcome Global Monitor, there is a wide variation in views among global Christians on the relationship between science and religion. Christians in the U.S., for example, far exceed Christians in other parts of the world in reporting that science has conflicted with their religion’s teachings: 61 percent of U.S. Christians reported such conflict, compared to 22 percent in Singapore, 18 percent in Sweden, and 12 percent in the Czech Republic. According to the National Association of Evangelicals, evangelicals in the U.S. are more than twice as likely as the general public (29 percent vs. 14 percent) to hold the view that science and religion are in conflict.

At the same time, for many other Christians science represents a path toward God, not away. “Doing science to me is a search for God,” George Coyne, a Jesuit priest, astronomer, and former director of the Vatican observatory told On Being podcast host Krista Tippett. “And I’ll never have the final answers, because the universe participates in the mystery of God.”

The growing distrust in science among some people of faith has become a matter of life and death during the COVID-19 pandemic. White evangelical Christians represent the highest rates of vaccination hesitancy among religious groups in the United States. How, then, are we to engage our neighbors, aunts, brothers, or parents in a way that counters misinformation and rebuilds trust?

Richard D'Souza and Eric Bell of the University of Michigan recently grabbed headlines for their discovery: The Milky Way once had a ‘sibling,’ which was devoured by the neighboring galaxy of Andromeda about 2 billion years ago. Their study, published in the Nature Astronomy journal last month, has its implications on the understanding of how galaxies evolve over time. D'Souza, the lead author of the study, hails from the Indian state of Goa and interestingly, he is also a staff member of the Vatican Observatory, an astronomical research institute supported by the Roman Catholic Church.

At UVA, one of the most popular study center offerings is the Faith, Reason, and Science Group, which has been a long-standing partnership with the Virginia Atheists and Agnostics. Participants might reflect on a chapter from a book by evolutionary biologist and atheist Richard Dawkins one week, and by geneticist and evangelical Francis Collins the next.

Just how religion plays into our biological impulse for empathy is not yet clear. One study from the University of Chicago shows that religious upbringing is associated with less altruism. Other studies have shown the contrary; a University of Warsaw study found that religious beliefs are positively associated with empathy, as empathic skills are crucial factors for religion.

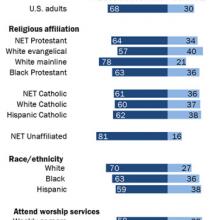

Image via Pew Research Center / RNS

Most Americans see a conflict between the findings of science and the teachings of religion.

But “see” is the operative word in a new Pew Research Center report issued Oct. 22.

Examining perceptions leads to some unexpected findings.

While 59 percent of U.S. adults say they saw science and religion in conflict, that drops to 30 percent when people are asked about their own religious beliefs.

It turns out that the most highly religious were least likely to see conflict.

In Jacob Needleman's newest book What Is God?, he examines some new ways of approaching one of the critical questions asked by humanity.