nativity

IN THE EIGHTH season of Call the Midwife, set in post-war east London, nuns and nurse midwives of Nonnatus House assist a woman with severe complications from a “backstreet” abortion. Sister Julienne says to a young nurse, “The word ‘midwife’ means ‘with-woman.’ A woman in that situation needs somebody by her side.”

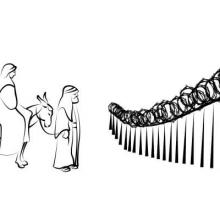

I’m pro-choice, which was an unpopular stance in the Catholic community I grew up in. For my views on reproductive rights, people in youth group called me a “baby killer” and “Pontius Pilate.” During Advent, specifically, I loathed the hollow teachings on Mary and childbirth. We sanitized the Nativity into a cute story — the equivalent of a Disney movie featuring a white family and a manger crowded with men. Only recently did I learn that some scholars believe that midwives attended Jesus’ birth. As reproductive freedom and care are further undermined in the United States, this is an apt time to reclaim a more feminist view of the Nativity and rethink Advent as the season of the midwife.

Every year from Dec. 16 to 24, Las Posadas begin in many Latin American countries and immigrant communities in the U.S. Roughly translated, posadas means “inn” or “shelter.” Las Posadas recalls the events in Luke’s Gospel leading up to Jesus’ birth. It’s a Catholic Christian observance with a sung liturgy that’s performed on the streets rather than in church.

A posada begins with a street procession that reenacts Mary and Joseph’s search for shelter at an inn. Those playing the protagonists of the story, Mary and Joseph, are dressed in costume and carry candles as they follow along a prescribed route, knocking on doors. At each door they ask, through special posada songs, for room at the inn. In rural areas, Mary may even ride on a donkey.

LAST DECEMBER, my daughter, Zipporah—who has taken to acting out the Christmas story using our wooden nativity set—observed that our crèche was missing a “mean king” figurine. That got me to thinking: I have never seen a nativity set with a King Herod figure.

We tend to close the curtains and go home for a family dinner right after the Magi bow before Jesus with their gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh.

But after the Magi head home, Joseph is warned in a dream to escape Herod’s genocidal tyranny by fleeing to Egypt with his wife and child.

We don’t know how the Holy Family was treated when they reached that foreign country. Were they welcomed or feared? Did Egyptians help this vulnerable family to resettle or did local carpenters fret that Joseph might steal their jobs? Was Jesus befriended by other children or viewed as a potential disease-carrier?

Compassion for the world’s estimated 21.3 million refugees—individuals who have fled their countries because of a credible fear of persecution—competes with our own fear that the violence they flee might impact us. This polarized reaction shapes the response by the United States and others to the global refugee crisis.

Nine in 10 Protestant pastors in the United States say that, as Christians, we have a biblical responsibility to care for refugees and other foreigners based on clear biblical injunctions, according to LifeWay Research. The same survey found that only 8 percent of local churches are helping refugees—nearly half acknowledged a sense of fear in their congregations regarding the arrival of refugees.

White evangelicals, by a margin of 2-to-1, were opposed to increasing the number of Syrian refugees admitted to the U.S., according to the Pew Research Center. (A majority of white mainline Protestants were also opposed and a slim majority of Catholics and black Protestants were in favor.) It’s ironic that followers of Jesus would be so afraid of refugees, given that we worship one!

At this time of year, we often see animals subjected to cruel holiday stunts, or treated as living props in our confusing pageantry.

Domino’s Japan recently announced it was canceling its ill-conceived plan to train reindeer to deliver pizza, following a PETA Asia campaign. And just this week, a man was charged with abusing a camel that was part of a hospital’s live Nativity scene in Pikeville, Ky.

As Pope Francis officially opened this year’s Christmas Nativity scene in St. Peter’s Square, he said Jesus was a “migrant” who reminds us of the plight of today’s refugees.

Francis told donors who contributed both the Nativity set and an 82-foot tree that the story of Jesus’ birth echoes the “tragic reality of migrants, on boats, making their way toward Italy,” from the Middle East and Africa today.

Tree lighting ceremony in Bethlehem. Image via REUTERS / Ammar Awad / RNS

The Star of Bethlehem is the name given to an event in the night sky that the Gospel of Matthew says heralded the birth of Jesus. Three wisemen — or magi, or kings — come to King Herod and ask, “Where is the one who has been born king of the Jews? We saw his star in the east and have come to worship him.”

Sculpture of Mary and Elizabeth and Church of the Visitation in Jerusalem. Creative Commons license.

In America, baby showers are times for women to come together and celebrate new life; presents are exchanged, advice given, and games played. Mary and Elizabeth celebrated the new life within them by exchanging presents of joy, encouragement, song, and prophecy. Both women were carrying children of promise. Neither woman had a convenient pregnancy. Mary and Elizabeth’s celebration shows the importance of women coming together for prayer, praise, and prophecy.

I need a word of hope.

In verse 1 of chapter 2 of Luke’s gospel we are introduced to a word of hope, a person who in the ancient Roman empire was referred to as “Divine, Son of God, God, God from God, Lord, Redeemer Liberator, and Savior of the World” and his name is…

No. Not Jesus.

Caesar Augustus.

All these terms are first used of Caesar Augustus. We use them in reference to Jesus because the gospel is a counterclaim against every other power. Every Christmas carol is a protest song. That is, every Christmas carol is a protest song if we realize Christmas isn’t about God’s ticket to escape the world and its pain. Christmas instead is the powerful way God shows up "in person" to transform the world and our pain.

Both imperial Rome and the early church claimed that their good news came from Heaven. Both announce a gospel of peace, here on earth. The Roman Empire believed it of Caesar Augustus — the early church believed it only of Jesus the Messiah.

For some, today’s Bible reading with its talk of empires is too political. For others its talk of angels too spiritual. But today’s gospel reading wants us to open our eyes to the empires and open our ears to the angels and their protest songs.

Author's Note: As we close out Advent, when we so quickly determine what’s our legal right or what we’re owed or what “the Bible really says” when, after all, we’re just simply too quick to judge. In these days where we must affirm #BlackLivesMatter, where we must stand up for victims of rape and abuse, and where we must struggle with our LGBTQ sisters and brothers for full inclusion, sermons like this are humbly offered.

We know the Christmas story well.

Those of us that have grown up with regular, annual, church-going rhythms — we essentially hear this story once a year.

Even so, those with no regular church commitments — people from all walks of life, people of faith or no particular faith, people from varied faiths — if you asked your friend, your neighbor, your cousin, a stranger on the street, I bet at least 50 percent of the time they’d be able to share the gist of the story:

Jesus was born to a virgin named Mary.

Mary was married to a guy (named Joseph).

There were angels, and wise men, and shepherds.

And I think there was a manger.

We know this story well.

But we hear it so often it becomes rote — literally a mechanically, automatically, mindlessly routine on repetition in our brains.

Yeah, yeah, yeah — 6lb 8oz baby Jesus, in a manger, Virgin Mary, Adopted Dad Joseph, sheep, shepherds, angels, stars at night, wise men, white Christmas, Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer …

You get my point.

So, let’s hear the story one more time and lean in a bit to this wild world of dreams, angels, and ancient Jewish marriage contracts.

Wise men from the East came to Jerusalem, asking,

“Where is the child who has been born king of the Jews?

For we have observed his star at its rising,

and have come to pay him homage.”

They told him, “In Bethlehem of Judea;

for so it has been written by the prophet.” (Matthew 2:1b, 5 NRSV)

Waiting, preparing, journeying, hoping.

Advent.

Unless you’re newborn yourself, you may have experienced it before, many times over. Christianity’s rhythm is cyclic, repetitive. Still, in the same way that we can continually find new gusts of loveliness and truth in old Scriptures our eyes have taken in before, each Advent is a fresh encounter. Not because the story is new, but because the cosmos has changed – we have changed. The Word is new because the world is new.

I’ve decided not to worry about the earlier-than-ever start to Christmas commerce this year.

Shortly after Halloween, with hardly a nod to Thanksgiving, stores and advertisers began going full-bore on the supposed “Christmas package,” namely, gift-giving, family fun, decorating, and entertaining.

It’s sad — this annual effort to derive profits from a facsimile of a 1950s Christmas — but other things are a lot sadder: an elusive economic recovery, continuing gun violence, racial violence, religious extremism, mounting rage, and intolerance at home and echoes of the Cold War in Europe.

Let commerce tread the line between gauche and tacky — merchants have salaries and suppliers to pay, after all. We have a troubled world to care about.

The path to that care doesn’t go by way of Wal-Mart or Budweiser. It is God’s path, and it goes by way of anticipation, promises, prophetic vision, a birth, a life, a death, and over all of it a sustaining grace that cares little for our seasonal receipts but cares intensely about our lives.

Maybe it’s good that commerce has declared its independence from religion and decorum. That clears the way for faith to have its parallel season — not in competition with commerce, but as the deeper reality that commerce can never attain, the deeper meaning we yearn for.

I don’t know about you, but I’m pretty sure I have sung “O Little Town of Bethlehem” every year on Christmas Eve for my entire life. But I believe this carol’s lyrics, specifically the words of the first verse, invite a little more thought than we normally give them.

O little town of Bethlehem

How still we see thee lie

Above thy deep and dreamless sleep

The silent stars go by

Yet in thy dark streets shineth

The everlasting light

The hopes and fears of all the years

Are met in Thee tonight

For now let’s ignore the historical inaccuracies of the song, and focus on what the words mean, especially the last four lines. How beautiful is it that through the dark world a light came to bind together the hopes and fears of all the years (I choose to see it as past and future) in Jesus?

Advent candles lit round the world declare our longing for the coming of Christ. We wait. And, in our waiting we hope, we pray, we yearn. Advent is a season where our energies and passions for all things to be made right are kindled. Christ, the precious Baby in the manger, is coming for us all to celebrate. Consider Him.

Despite the hunger, the fatherless, the ailing. Despite the wars and senseless violence. Despite all of the reasons to say there is no redeemer.

We wait for the Christ child.

Our faith is rooted in such anticipation. Mockers have innumerable examples to declare the reasons why God is dead. Centuries of proof. Holocausts, molestation, shame. The Church waits despite its own pollution and contribution to the lack of justice.

Yet these things merely point to the coming of the Child. If the world were made right by our collective longings for occupation, for the 99 percent, for cosmic good, we’d see equitable dispersion of wealth, of food, of housing. We’d live the Marxist dream of community. We would all be haves.

In the church where I grew up, the first Sunday in Advent was dubbed the “hanging of the greens.” On that special Sunday, we sang carols in the decorated sanctuary, all culminating in the children’s live nativity scene. The service never changed from year to year. The only variables were how many kids needed roles and which young child would get stage fright, thus leaving part of the the story without visual representation.

It always seemed like the doves were cursed. The doves rarely remained on stage for the entire performance. Over the years, I was a variety of animals — a wise man, a shepherd, and finally Joseph. I never got stage fright. I was never a dove. I can only imagine what my mother would’ve done if I had been that kid.

It took me years to realize that there was a character missing from my congregation’s telling of the story. We always left out King Herod.

This was a huge oversight, because Herod plays a major role in Matthew’s account of Jesus’ birth.

This Advent, as we wait for the true light who is coming into the world (John 1:9) we pause and reflect on our Christmas hope. As a friend said last night, we do not linger forever in uncertainty but as an expectant mother who labors in anticipation of the joy her child will surely bring.

Our assurance of salvation — past, present, and future — depends on the unique person of Jesus Christ and our relationship to him, and there's perhaps nothing more central to Jesus and our relationship with him than that he became flesh, was made like us in every respect (Heb. 2:17), so that by grace we might become partakers of his divine nature (2 Peter 1:4).

This isn't something the church merely teaches but an event of history, revealed for all men and women in the one-of-a-kind person Jesus is, the human and divine Son of God. From the moment of Christ's conception, eternity himself inhabits time so that events of his life on earth long since past are forever present to us in Jesus. This is one reason our joy at Christmas is so palpable and real ... when we worship Jesus at Christmas, we are once again with Mary and Joseph on that cold, dark night as they swaddle “he who made the starry skies” and lay him in a manger.

Advent suggests so many mysteries of God's patience. One rarely commented case is God as Father and embryo. It is extra Biblical so imagination can only begin to tell the bizarre tale. Gabriel's annunciation and appearance to Joseph begins the period of waiting and soul searching, but a remarkable gap exists in the Advent story. Luke 1:56 makes this cursory remark as though it would suffice:

Mary stayed with Elizabeth for about three months and then returned home.

Presumably the second trimester of Mary's pregnancy is treated with a passing reference. If we simply take the divine conception of Jesus at face value, there was a moment in human history where God existed as Father in the heavens and embryo in Mary's uterus. Paradox of paradoxes. The Creator in utero.

One of the most fresh and challenging interpretations surrounding the Christmas narrative was produced by South Africa’s renowned theologian, the late Steve de Gruchy. In regards to the Magi and their visit with Joseph, Mary, and the newly born Jesus in Matthew 2: 1-12, de Gruchy offers a striking proposal surrounding the biblical text and its direct relationship with cooperative efforts between those in the so-called global north and south.

...

Among other things, a key insight into this portion of the Christmas narrative is that God is revealed through the vulnerability of poverty and marginalization. The main characters of the Christmas plot are not wealthy and prosperous high-rollers, but the downtrodden and vulnerable poor who stand as deliberate reminders of how God is in solidarity with those who are too often forgotten and oppressed. If Mary and Joseph were people of wealth and privilege, they surely would have received room at the inn, yet God shows an alternative to the common hierarchies of status in our world, and such pushed-aside people are given highest priority as the bearers of Christ.

There is a line from a Gerard Manley Hopkins poem about the Virgin Mary that describes the baby Jesus as “God’s infinity, dwindled to infancy.” The line captures perfectly the beautiful but also shocking idea, central to Christianity, that the infinite God who created the universe also chose to descend, dwindle, become small, become helpless, become dependent on human beings.

Hopkins is right: the baby Jesus is not merely a sentimental or cute idea but is potentially radical, transformative, and controversial.

Are you put out that a community nativity display was nixed by a city council? Did a checkout clerk greet you with "Happy Holidays" instead of "Merry Christmas"? Maybe Christmas music annoys you when the Advent fast hasn't even arrived?

Not me. I am not compelled to "reclaim" or "rescue" Christmas from the many who ignore and the few who despise its magnificent origins.

How can I be anxious or offended? I am in too much awe of its startling truth: that a baby is God, gasping for air, clasping for mother's milk, flailing his small limbs in a feed trough; taking on my frailty, contingency, vulnerability, that I might partake in his everlasting nature.

The baby is now Lord of all things visible and invisible, forever "one of us," still bearing his now glorified, nail-scarred flesh at the Father's side, making all things new for all persons, hallowing the far-flung cosmos — matter's maker now made matter, redeeming every atom and every stoney heart. This reality overpowers me with its brilliant mystery.