The Leftovers

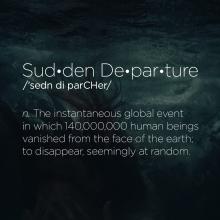

I FIRST BEGAN watching The Leftovers, HBO’s drama based on a novel of the same name by Tom Perotta, when it debuted in the summer of 2014. Like many viewers, I was fascinated by the premise: On Oct. 14, 2011, 2 percent of the population suddenly disappears in a rapture-like event. The show begins three years after what is called the “Sudden Departure,” and rather than explaining the metaphysical meaning of this mysterious event, it focuses on how the members of one family process their grief.

Throughout the show’s first season, we’re introduced to an array of characters who deal with the Sudden Departure in different ways. Some want to continue with life as it was on Oct. 13, 2011, before the world changed. Some are tortured by the mystery of the Departure and why they weren’t “taken.” Some seemingly well-adjusted people join the cults that have sprung up since the event. One group in particular has gained the most traction, the Guilty Remnant. The group exists to be “living reminders” of God’s judgment; they make it their mission to make people remember, but offer no comfort. Another cult features a messianic leader who promises to absorb the pain of anyone who hugs him, but offers no spiritual or intellectual balm for the hurt and confusion post-Departure.

The novel on which the show is based was written as a response to the way the world changed after Sept. 11, so it was particularly poignant that the attacks in Paris occurred as I watched the second season of The Leftovers. Certainly it’s grievous to see violence occur anywhere, but as with Sept. 11, the attack on Paris brought with it a shocking cognitive dissonance: That kind of thing doesn’t happen in places like this—Western, cosmopolitan, relatively safe. Before the attack in Paris, before the Twin Towers fell, there was always the possibility that something tragic could occur on a random Friday night or Tuesday morning. But perhaps to many of us who live in relative comfort and ease, violence and tragedy are what happens to other people, in other places. It is this cognitive dissonance and the subsequent question of how to live in uncertain times that the second season of The Leftovers explores. It is also what makes it worth watching.

As a native New Yorker, I can never forget Tuesday, September 11, 2001. I was in college, but heading to my part-time job that morning. My car was being fixed, so my father drove me to work. There was an unusual amount of traffic and as we turned on the radio, we heard a reporter talk about a plane that hit the World Trade Center.

The first thought we had was that this was an accident. It had to be an accident, right? As we listened to the reports though, the second plane hit and it was clear that something was very, horribly, terrifyingly wrong.

From our office in Queens, we watched the towers burn and then collapse. The image of the great cloud of smoke and debris encompassing the skyline has been burned on my brain. And a few days later, while handing out sandwiches to mourners at the makeshift memorial at Union Square with my parents’ church and non-profit organization, the feeling of hugging a total stranger while she wept on my shoulder will never leave me.

It is impossible to forget.

I must admit the timeliness on the part of HBO to air the season finale of The Leftovers in the week of 9/11. Tom Perotta, who authored the play on which the show is based, purposely included allusions to 9/11. Rather than a theological treatise on the Rapture, it is a beautiful case study in grief and the excruciating tension between the desire to move forward and the need to remember.

Editor's Note: Spoilers ahead! You've been warned.

Over the past eight episodes of The Leftovers, HBO’s latest drama based on Tom Perrotta’s play of the same name, viewers have been treated to a case study in grief and faith in the midst of a life-changing event. Unlike the Left Behind series, which incorporated Christian triumphalism with terrible theology, The Leftovers examines the deeper human and spiritual issues of what would happen were two percent of the population to suddenly disappear. It is powerful and beautiful and really hard to watch (especially Episode Five). It asks the question: does life go on when your world is changed forever?

The show offers a variety of responses to the Sudden Departure of October 14: Kevin Garvey, the police chief who seems to be losing his mind after his wife leaves him for a cult and after his father needs to be committed; Nora Durst, who’s lost her entire family, so she keeps everything exactly as it was when the Sudden Departure occurred; Rev. Matt Jamison, Nora’s brother whose faith has been shaken because he was not taken; the town dogs who have become feral; and finally, the creepiest citizens of Mapleton, the Guilty Remnant, or the GR as they’re “affectionately” known.

This past week’s episode gave us a greater understanding of the GR. Although the nihilistic views of the Guilty Remnant are quite different from those of Christianity, I was struck by their powerful and strategic mission of witness. The cult was formed out of the recognition that everything changed on October 14 and that to pretend otherwise was foolish. The group, in their white clothes, their silence, their stripped-down existence, bears witness to the fact that they are living reminders of what happened. They are fundamentalists about their cause and willing to die for it — even if that death comes from their own hands.

HBO’s “The Leftovers” is the feel-good series of the summer, if your summer revolves around root canals and recreational waterboarding.

Indeed, it’s pretty grim stuff — but quite engrossing and worth your time, thanks to intense performances by Justin Theroux and Christopher Eccleston, and the way creators Tom Perrotta, who wrote the book on which the series is based, and Damon Lindelof, best known for screwing up the end of “Lost,” unflinchingly tackle the nature of grief and the limits of faith.

Can you call it an apocalypse if you can still get a decent bagel afterwards? It’s three years after what has been termed the Sudden Departure, when 2 percent of the world’s population — Christians, Jews, Muslims, straight, gay, white, black, brown, and Gary Busey — suddenly disappeared.