Ireland

With 1,365 parishes that include 2,646 churches across 26 dioceses on the island of Ireland, the initiative has the potential to make a difference to local biodiversity as well as create awareness of global conservation efforts, particularly the agreement of countries at the 2022 United Nations conference on biological diversity (COP15) to return 30 percent of land to nature. It also strives to increase awareness of church teaching on ecology and highlight the role of people of faith in protecting creation.

The Banshees of Inisherin has received several awards from the Golden Globes and multiple nominations for the forthcoming Academy Awards. It’s not hard to see why: Martin McDonagh’s film captures the complex, deep turmoil of a friendship falling apart. The friendship falls apart because the characters don’t have the framework to work through misunderstandings due to their depressive state.

WHEN MARI STEED began searching for her birth mother in Ireland, she knew little about the system of secrecy and abuse that would lead her to co-found a social justice group to right its many wrongs. Born in 1960 in a convent-run “mother and baby” home in County Cork, Steed was one of more than 2,000 “banished babies” adopted from Ireland to the United States beginning in the 1940s. As an 18-month-old, she was taken to Philadelphia.

When Steed became pregnant as a teen, she was put in a Catholic-run home in Philadelphia and made to give up her child. In the mid-1990s, she decided it was time to find both the daughter who had been taken from her and the birth mother from whom she’d been taken. Her American family were “decent people,” Steed told me. “I don’t have any serious qualms with my upbringing. But I did begin to search for my mother to find out more about where I’d been.” She created a website to connect with other adopted people of Irish birth.

Eventually, Steed learned her mother, Josie, had given birth to her out of wedlock and had been born to an unwed mother herself. In Ireland, such circumstances put Josie on the full merry-go-round of church-and-state institutions before the age of 30: a county home, an industrial school, 10 years in a “Magdalene laundry,” and finally the mother and baby home. Steed, who lives in Virginia now, recalled she at first had no clue what all this information meant. “‘What are laundries?’ I didn’t even know what that was at the time.”

The answer led Steed down a rabbit hole of secrecy and obstruction. Originally founded in the 18th century as places of refuge for so-called “fallen women,” Magdalene laundries evolved into institutions where women and girls labored for no pay as penance for transgressing Catholic Ireland’s moral and class codes. In his book Ireland’s Magdalen Laundries and the Nation’s Architecture of Containment, Boston College professor James M. Smith described a system of interconnected institutions “including mother and baby homes, industrial and reformatory schools, mental asylums, adoption agencies, and Magdalen laundries.” (Ireland’s first such institution was called the Magdalen Asylum for Penitent Females, using an archaic spelling of Magdalene.)

Pope Francis concluded his recent trip to Ireland with a Mass at the World Meeting of Families, during which he called on families to “become a source of encouragement for others.” What sort of encouragement does he envision, I wonder.

Standing just a few feet away from where many Catholics believe the Virgin Mary appeared in 1879 to a dozen denizens of this bucolic corner of western Ireland at the height of a famine, on Sunday morning Pope Francis begged God’s forgiveness for the abuse of countless innocents by priests and other members of the Catholic Church.

Francis will pray at the Knock shrine as part of his two-day visit to Ireland this week, the first by a Pope in almost 40 years that have transformed the once staunchly Catholic country into a far more secular and liberal society.

The vote overturns a law which, for decades, has forced over 3,000 women to travel to Britain each year for terminations that they could not legally have in their own country. "Yes" campaigners had argued that with pills now being bought illegally online abortion was already a reality in Ireland.

Tragically, the separation of spirit from matter has tainted the way we see all of humanity. In the past, it was used to justify violence against the Native Americans, and in the more recent past we’ve dismissed thousands of casualties from wars in the Middle East. We have leaders today who consider war in Korea palatable because “if thousands die, they’re going to die over there.” This is a direct result of a theology that cares more about souls than it does bodies. It’s much harder to love our neighbor if we don’t see the divine, the Christ, within them. It makes it much easier to characterize entire swaths of people groups who don’t have “Jesus in their hearts” as being the enemy. It continues to pervade modern day missions that typify non-Christian cultures around the world as savages living in darkness, rather than looking for the light that is already present and using that as the starting point.

In a major setback for the pope, Collins on Mar. 1 announced that she had resigned from the Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors, established by the pontiff in 2013 to counter abuse in the church.

She said the pope’s decision to create the commission was a “sincere move,” but there had been “constant setbacks” from officials within the Vatican.

“There are people in the Vatican who do not want to change, or understand the need to change,” Collins said in a telephone interview from Dublin.

Pope Francis has condemned clerical sex abuse as an “absolute monstrosity,” and asked victims and their families for forgiveness on behalf of the Catholic Church.

In an unusual move, the pontiff’s comments were published as a preface to a new book by Daniel Pittet, a Swiss victim who was sexually abused for four years by a priest when he was a child.

A religious order covered up the sexual crimes of an Irish priest who abused more than 100 children, some as young as 6, according to a new report.

The failures of the Salvatorian order to act on the crimes of a priest named “Father A” were outlined in a report released May 4 by Ireland’s National Board for Safeguarding Children in the Catholic Church.

When Ireland became the first country to legalize same-gender marriage by popular mandate, double rainbows appeared over Dublin, and an Irish rock band transformed their Arizona concert into a gay-rights celebration. Almost 30 years ago, Bono endured threats from angry Arizonans for his support of the U.S. national holiday for the late Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. But on Saturday, Bono invoked King as peacemaker as U2 celebrated the victory of love, turning the song “Pride (In The Name of Love)” into an anthem for gay pride.

...

Bono shared, “This is a moment to thank the people who bring us peace. It’s a moment for us to thank the people who brought peace to our country. We have peace in Ireland today! And in fact on this very day we have true equality in Ireland. Because millions turned up to vote yesterday to say, ‘love is the highest law in the land! Love! The biggest turnout in the history of the state, to say, ‘love is the highest law in the land!’ Because if God loves us, whoever we love, wherever we come from … then why can’t the state?’”

In many ways, Ireland remains a heavily Catholic country.

Yet the emphatic “Yes” vote to same-sex marriage rights on May 22 represents a seismic shift in the nation’s social liberalization and challenges the Roman Catholic Church to rethink its role in Irish society.

“In Ireland,” says a character in a 1904 George Bernard Shaw play, “the people is the Church, and the Church is the people.”

But not so much anymore.

On May 22, voters in this once deeply Roman Catholic country will decide whether the country’s constitution should be amended to allow for gay marriage. If the amendment passes, Ireland will become the first country to legalize same-sex civil marriage by popular vote.

For Catholics, Episcopalians and some Lutherans, March 17 is the Feast Day of St. Patrick. For the rest of us, it’s St. Patrick’s Day — a midweek excuse to party until we’re green in the face. But who was Patrick? Did he really drive the snakes out of Ireland or use the shamrock to explain the Trinity? Why should this fifth-century priest be remembered on this day?

Q: Was St. Patrick a real guy, and would he approve of green beer?

A: Yes, Patrick was a real person, but not much is known of his life. He was born in the late 300s when the Roman Empire extended to England, so he was not “really” Irish — like the vast majority of people who celebrate his day. In his “Confessio,” one of only two surviving documents attributed to him, Patrick wrote that while his father was a Christian deacon, he was not devout. At age 16, Patrick was captured by Irish marauders, carried across the Irish Sea and enslaved. Patrick spent six years alone in the wilderness tending his master’s sheep, praying constantly. “It was among foreigners that it was seen how little I was,” he wrote. He began to have visions and hear voices that told him: “Look, your ship is ready.” So Patrick left his first flock and walked 200 miles to the coast. It’s a pretty safe bet he would have loved a beer, green or otherwise, as he stepped into a boat bound for England.

I GREW UP IN RURAL IRELAND in the 1950s in a world surrounded by trees.

Close to my home, a ribbon of horse chestnuts lined both sides of the road. Each summer their intertwining canopies shut out the light, which gave the road its name—the dark road. In the fields around our house there were stands of oak, birch, elm, and sycamore. About 40 yards to the south and west, my father planted a shelter belt of Leylandii. We had different varieties of apple trees in the orchard, and two pear trees.

In 1962, just as the Second Vatican Council was beginning, I entered St. Columban’s seminary to be a priest. The seminary was located on a large estate called Dowdstown in County Meath. More than 150 acres were covered in woodlands full of indigenous trees such as oak, hazel, holly, ash, Scotch pine, willow, elm, and rowan. There were also exotic species, including a number of the sturdy cedars of Lebanon, a variety of cherry trees, and even a few California redwoods. The folklore in the area was that the trees had been planted in the 1820s by Gen. Robert Taylor, who had fought alongside Wellington at the Battle of Waterloo.

Trees are the dominant life form on land—and the longest-lived creatures on earth. During my seven years in seminary, while studying philosophy, theology, spirituality, and scripture, we never once looked to the natural world or trees for insight into our relationship with God, other human beings, or other species. And there is so much to learn! Sadly, theology and scripture presentations were isolated almost exclusively to the divine-human relationship, with little consideration given to the rest of creation.

WHAT’S A GOOD priest for? So asks Calvary, the second feature film from writer-director John Michael McDonagh, rooting itself in Ireland’s coastal landscape, centering on a pastor threatened with scapegoat-retributive murder from a grievously sinned-against parishioner. Its vibe owes a great deal to the quiet reflection of films such as Jesus of Montreal and Au Hasard Balthazar (in which a donkey evokes the love and wounds of Christ), and the archetypal Westerns High Noon and Unforgiven. Brendan Gleeson plays a priest who was drawn into the church after his wife’s death, which allows us the rare experience of seeing a cinematic Catholic priest who is both a parent to his flock and to a beloved daughter, who feels somewhat abandoned by his commitment to the church.

Gleeson has the uncanny ability to hold his massive frame as both solid—almost concrete—and vulnerable. Knowing that everyone is both broken and breaker, his Father James is healing on behalf of a flawed institution, although he doesn’t confuse vocation with a job. His bishop’s response to a request for help is “I’m not saying anything,” reminding me of Daniel Berrigan’s challenge to religious hierarchies, heard at a public meeting in Dublin in the run-up to the Iraq war: “In Vietnam, they had nothing to say, and said nothing; now, they have nothing to say, and they’re saying it.”

Father James understands the difference between stewarding power and grabbing it (one obvious signal of his goodness), and he is up to his neck in the community, running the gamut from friendship with an American writer looking for inspiration in the land of his presumed ancestors to a visit with a former pupil whose own inner darkness has led him to do monstrous things.

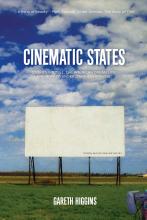

Lots of people like movies; Gareth Higgins loves movies. But the founding director of the Wild Goose Festival and long-time peace activist engages popular culture with a different eye than most of us. And he’s used that keen eye for deeper meaning to create his latest book.

I asked Gareth about his new book on American film, his peace work, and what it’s like considering American culture both as an insider and as a non-native. Here’s what he had to say.

DUBLIN — Patricia Wojnar left a 32-year career in interior design to pursue a degree that wasn’t in demand: a master’s in bereavement studies.

Having seen four family members die early, she wanted to understand how to adapt.

As it turned out, the degree perfectly prepared her to enter one of Ireland’s emerging professions.

Wojnar is now a registered civil celebrant, presiding over funerals and weddings for people who refuse to associate with Ireland’s scandal-tarred Roman Catholic Church. She’s not alone; many newly minted civil celebrants are starting their own businesses as part of Ireland’s “post-Catholic” economy.

Although many observers have noted the impact of secularization and child abuse scandals on church membership and finances, only now are the Irish seeing the cultural and socioeconomic reverberations. These include a class of people willing to observe life’s most significant milestones outside the church.

DUBLIN, Ireland — Ruth Bowie was in the throes of grief when she found out she would never know her unborn child. At the 12-week mark, a pregnancy scan showed the baby had anencephaly, a fatal condition in which a portion of the brain and skull never form.

Bowie, 34, a pediatric nurse, knew the implications of the birth defect even before the doctor explained. But the life-changing news didn’t stop there.

“The doctors said we will continue to look after you, or else you can choose to travel,” she recalled.

Put another way, if she and her husband wanted to seek an abortion, they would have to travel to England to end the pregnancy.