Doubt

It was the beauty on the outside that drew me away.

Before social justice became trendy among evangelicals, people of all denominations, faiths, and philosophies had already been steadily working in the trenches without fanfare, caring for the least of these with a quiet strength.

Through seminary, I learned to grapple with justice being at the heart of the Christian Gospel — dignity, equality, and right to life for all — I marched out into the real world with zeal and vigor to champion the rights of the oppressed in the name of Jesus. However, I discovered the people who were doing this work often had no identification with Christianity, that those outside of church were behaving more Christian-ly than some inside.

I admired Nicholas Kristof, a self proclaimed nonreligious reporter, who tirelessly sheds light on humanitarian concerns.

I adored Malala, a Muslim, who stood up to the Taliban to bravely demand a right to education for girls.

I reflected on the justice heroes of recent history, people like Gandhi and countless other humanitarian workers who don’t claim the Christian faith for their own.

It disoriented me because for so long I believed it was only through Christ that one can walk in righteous paths; that without the Truth (which had been so narrowly summed up for me in John 3:16), everything was meaningless. I didn’t have an interpretive lens to categorize beauty that existed outside of the vessel I was told contained the only beauty to be found: the evangelical Christian church.

Faith: dealing with the meaning of life, the matter of eternal salvation — the bedrock upon which we build our families and society. This is serious stuff. Irreverence, by definition, is a lack of respect for that which is serious. It would seem that finding faith in the irreverent is impossible, like searching for the sun in the dark of the night.

Irreverence permeates pop culture. From HBO shows filled with crude nudity and violence, to musicals such as The Book of Mormon (where explicit ratings are applied to almost every song), to late night comedies featuring popular hosts like Jon Stewart and Colbert, who play-act a persona speaking exclusively in snark.

The Church, by and large, keeps irreverence at arm’s length. Sure, some pastors like to open sermons with a couple of clean jokes, but that’s about the extent to which humor interacts with the Faithful. While I agree there’s a social maturity required in expressing irreverence through appropriate channels, the Church is missing out on a deep authenticity of the human experience if we continue to fear irreverence instead of finding beauty in it.

“On the third day, he rose again.”

But how that statement is interpreted is the source of some of the deepest rifts in Christianity — and a stumbling block for some Christians and more than a few skeptics.

Did Jesus literally rise from the dead in a bodily resurrection, as many traditionalist and conservative Christians believe? Or was his rising a symbolic one, a restoration of his spirit of love and compassion to the world, as members of some more liberal brands of Christianity hold?

In a world where people are craving inspiration, growth, and information, many churches maintain a cyclical pattern based on redundancy, safety, and closed-mindedness. Unfortunately, many pastors and Christian leaders continue to recycle old spiritual clichés — and sermons — communicating scripture as if it were propaganda instead of life-changing news, and driving away a growing segment of people who find churches ignorant, intolerant, absurd, and irrelevant.

As technology continues to make news and data more accessible, pastors are often failing to realize that they're no longer portrayed as the respected platforms of spiritual authority that they once were.

Instead of embracing dialogue and discussion, many Christian leaders react to this power shift by creating defensive and authoritarian pedestals, where they self-rule and inflict punishment on anyone who disagrees, especially intellectuals.

From Julie Andrews’ performance as Maria in the 1965 film “The Sound of Music” to Meryl Streep’s portrayal of Sister Aloysius Beauvier in “Doubt” (2008), many Hollywood actresses are particularly conspicuous for their habits. But although habits or veils are thought to symbolize purity – and especially chastity — some films presented a more complicated portrait of nuns.

The title of Maureen Sabine’s new book, “Veiled Desires: Intimate Portrayals of Nuns in Postwar Anglo-American Film” (Fordham University Press), refers to the paradox of having charismatic and photogenic actresses playing chaste nuns and, in the process, drawing attention to the desires their habits were thought to stifle.

Every day, my previously stable faith is replaced with a little more hungry curiosity. I consider this progress.

I posted this brief statement on my Facebook and Twitter accounts yesterday and promptly received quite a bit of interest in return. Not surprising, really, that my typical readership would resonate with such a claim, but I also found some surprising affirmations from those I would not have expected to appreciate my sentiments.

I write fairly often about moving away from emphasis on a propositional faith and toward one that is more implicitly lived out in our daily experience. Said another way, I would much rather have the teachings and values shared by Jesus revealed through my actions and through what people see in me, rather than simply through any particular rhetoric that I offer them as an act of persuasion, or even coercion. This is also selfishly motivated, as I am increasingly convinced that, whereas a faith centered on the proclamation and defense of particular statements is one that lends itself to inertia, a way of life that reveals your values without explicitly having to state them is both more compelling to others and more fulfilling for ourselves.

LAST YEAR on NPR’s “All Things Considered,” I heard the story of Teresa MacBain, a United Methodist pastor who came to the conclusion she was an atheist. The situation was scary and awkward for her. Who could she tell? What would she do now for a living?

She wasn’t trained for any other occupation, but neither could she continue her double life of preaching and public praying while knowing she didn’t believe in any of it.

Lacking someone to confide in, MacBain secretly confessed to her iPhone, “Sometimes I think to myself: If I could just go back a few years and not ask the questions and just be one of the sheep and blindly follow and not know the truth, it would be so much easier. I’d just keep my job. But I can’t do that. I know it’s a lie. I know it’s false.” Eventually, she left the ministry.

As I listened to MacBain’s interview, I empathized with her. After 30 years of serving as a Mennonite pastor, I often wonder whether I still believe the things I’ve always said I believed. My questions about God have become deeper, while my previous answers now sound shallow. The thought that I might not believe in God is frightening. It threatens my identity and worldview—not to mention my occupation. And yet I haven’t arrived at MacBain’s atheism. Instead, my doubts have been folded into my faith.

During the Christian spiritual journey, followers of Christ are forced to eventually face some basic faith-related questions. Here are a few of the most common ones:

1) What is salvation?

What does salvation really mean? When does it happen and is it permanent? Do you choose your own salvation or is it predestined? Is everyone saved or just a select few?

The idea of salvation is extremely complex, and our concept of it directly influences how we live, evangelize, and interact with the people around us.

Vampire Weekend are a little like a college-educated version of the rich young ruler in Mark 10. I say a little because, despite the fact that they have gotten flack for being “privileged, boat shoe and cardigan loving Ivy League graduates,” the New York-based foursome actually probably aren’t as wealthy as skeptics think, and the late 20-somethings probably haven’t been as straight edged as the rich young ruler. I mean, they’re rock stars. And even though they went to Columbia University, rock stars aren’t widely renowned for their moral rigidity.

But on Vampire Weekend’s third album, Modern Vampires of the City, which was released last month to critical acclaim and commercial success, we find lead singer Ezra Koenig asking honest questions of God, much like the young ruler.

On this album, the third in what Koenig sees as a trilogy, Vampire Weekend manage to mature their poppy, eclectic sound, drawing from all sorts of genres and international songs — as they normally do — but also exploring deep questions of morality, love, faith, and belief in complex ways.

TWO YEARS AGO, Jeff Chu found himself at a crossroads. Like many gay Christians, he felt disconnected—condemned by a wide swath of his fellow believers because of his sexual orientation, questioned because of his faith by some in the LGBTQ community who have been pushed out of the church by the words and actions of many Christians. To top it off, there was that lingering doubt, so common among those raised in evangelical households: Does Jesus really love me?

To answer that question, Chu—an award-winning writer for Time, The Wall Street Journal, andCondé Nast Portfolio and the grandson of a Southern Baptist preacher—took off on a yearlong cross-country pilgrimage, “asking the questions that have long frightened me.” What he encountered was a divided church, “led in large part by cowardly clergy who are called to be shepherds yet behave like sheep.”

Many of the pastors Chu contacted for the book refused to speak with him, citing their suspicion of him as a member of the so-called “‘liberal media elite’” or stating bluntly that engaging on such a controversial issue might jeopardize funding for a pet project. After speaking with Richard Land, then-president of the Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention, and David Shelley, a Baptist minister from Tennessee affiliated with the Family Research Council, Chu concludes that they “devote much more time talking about legislation than about love.”

Then there are those he interviewed who are known more for screaming than talking. In meeting with members of the infamous Westboro Baptist Church, Chu does not shy away from controversy—or his own fears. “Some nights before my departure,” he recalls of the days before his trip to Kansas, “I had nightmares, and many mornings I’d wake with my jaw tight and teeth clenched.” His encounter with Rev. Fred Phelps, the grizzled, homophobic pastor of the church, is perhaps the most riveting of the book, culminating in a surreal, grudging offer of friendship from Phelps.

Making an ultimatum about church attendance to a sleep-deprived teenager may be my own version of hell on earth.

“We are leaving for church in 10 minutes,” I said, summoning my most authoritative voice before the lifeless lump under the covers.

My seven-year old Annie Sky watched the tense exchange between me and my 14-year old daughter Maya, who made periodic moans from the top bunk. With furrowed brow, my first grader sat on the couch, as if observing a tiebreaker at Wimbledon with no clear victor in sight.

For a moment, I wondered why I had drawn the line in the Sabbath sand, announcing earlier in the week that Maya would have to go to church that Sunday morning after an all-day trip to Dollywood with the middle school band. Somehow I didn’t want Dolly Parton’s amusement park to sabotage our family time in church. (The logic seemed rational at the time).

When Maya lifted the covers, I glimpsed the circles under her eyes and sunburn on her skin. But I repeated my command, with an undertone of panic, since I wasn’t sure if I could uphold the ultimatum.

When she finally got into the car, I breathed deeply and turned to our family balm, the tonic of 104.3 FM with its top 40 songs that we sing in unison. As the drama settled, I realized one reason why I made my teenager go to church: I want my daughters to know that we can recover from yelling at each other (which we had) and disagreeing. We can move on, and a quiet, sacred space is a good place to start.

HOW SHALL WE engage with scripture through all 50 days of Easter? There are clues in the haunting story of Jesus' appearance beside the sea of Tiberius. After Easter Day many of us are ready to let things quickly revert to normal. It is, strangely, both reassuring and uncomfortable to hear that those disciples, whose business had been fishing, wanted to get back to their boats so promptly after the horrors and wonders they had witnessed in Jerusalem.

Jesus is waiting for them by the shore with breakfast already cooking. All is ready, yet he wants them to bring some of what they haul up in their nets, so he can include samples of their own catch in the menu. And what a catch it was!

Easter is our time to experience the grace that is always ahead of our game and is underway for us before we are ready. Yet grace does not exclude what we bring to the table. Grace expects and includes the work of our hands, the weavings of our imaginations, and the gifts of our unique experiences. In one sense, Eastertide is more truly a season of repentance than is Lent. One thing we might need to repent of is our passivity—those times when we expect God to hand us on a plate the meaning we are hungry for. We need to bring our own bits to the cooking fire if we are to really eat with Jesus. It is part of the mix of grace that we must participate, not just receive.

It's an important question. Mark Driscoll, the famed neo-Calvinist, wants us to believe that we are God's enemies and God desired our destruction until Jesus, God's own Son, put himself in harm's way and saved us from God. Interesting theological gloss...but there's something in this I'm pondering right seriously this morning...

...What's it like to wrestle with the Divine One? You know, like Jacob did there in the desert one night. You can contend with God, can you not? Is God not then your enemy in some way? Well, perhaps your adversary? I don't know for certain if any of this language suits, but I'm pondering it because God and I are engaged in a cage match and I am mustering all the courage I have not to pull out a folding chair or some such mess knowing full well that God cheats.

I love Peter Rollins' honesty about his dark night of the soul.

He's popularized a term for the intellectual position accompanying the dark night of the soul: a/theism. I interpret Peter's thought as being in relation to an experience of God's absence. [Note: corrected this paragraph's content from "even coined" to "popularized. Turns out another author coined a/theism."]

I thought it was hilarious that Tony Jones challenged Peter to give up atheism for Lent on the Homebrewed Christianity podcast.

But I took it seriously when Micah Bales, one of my best friends, wrote a post challenging Peter Rollins' Atheism for Lent. You can't give up God because God is a felt presence. (Peter later responded to Micah. And Brian Merritt a piece about who Micah is.) Our conversations got me thinking about what I value about Peter Rollin's voice and what I might challenge about a/theism as I understand it. In order to talk about why a person believes or disbelieves in God, you have to talk about a personal spiritual journey.

JUST A FEW dozen pages into Faith, Doubt, and Other Lines I've Crossed, evangelical pastor Jay Bakker pens what may be the best explanation for the Christian emphasis on church community that I've ever encountered. Noting that doubt can be "hard and scary," Bakker writes: "That's why we have one another, why we have community. We can go through those days of doubt together. I wouldn't be who I am today if it weren't for the people who have been there with me as I question everything."

Many writers have grappled with the challenge that doubt poses for religious believers. But in this honest, searching, and ultimately uplifting book, Bakker pulls doubt out of the shadows where many believers wrestle with it on their own and instead presents it as a reality that Christian communities can and should address together.

Bakker's approach to the often-taboo topic of questioning—or, as he puts it, "the sense that faith is crap, life is meaningless, there is no God, the Bible is a fraud, Jesus was just a charismatic man turned mythological figure if he existed at all"—is shaped by his childhood in a Pentecostal environment that left no room for doubt. As Bakker ruefully notes in the book's introduction, "I will probably be 80 years old and still introduced as Jay Bakker, son of Jim and Tammy Faye." That unusual background only provides the impetus, however, and not the substance for this book, which reads mostly as the stream-of-consciousness meditation of a man pushing and pulling at his faith to see if it holds up.

I’m going to tell you something I do not do very well. But, only if you will not tell the other mothers because I have listened to them talk, and apparently I am the only one not very good at this. Deal?

I'm not good at helping my children learn to feed themselves. I totally get in the way. Let me explain.

Well, actually, there isn’t much about it to explain.

I don't like messes. So, I feed my children … for too long. I sit a bowl full of spaghetti in front of them, and I get a little panicky. I mean, have you ever found dried, crusted spaghetti noodles on the floor a week (or more) later when you're cleaning? And what about the slimy, greasy residue left on the plastic tray attached to the high chair? And then there's the highchair cover. I did not realize you could take that thing off to clean it until my second child was two. Wow. That was amazing — what I found under it, I mean.

Never mind the fact that most of the food gets on the child and everything and everyone else … not in their mouths.

And, I mean, I'm also very concerned about my child’s dietary needs. Seriously, I think that is the biggest reason I insist on feeding them well into their third year. (Did I just write that?) They need me. They need me to spoon that mouthful of spaghetti straight into their teeny little mouth. That way I know where it goes — there is no guesswork.

Reentry is often a pain in my ass.

It's true. I get a chance to get away from it all, to spend some time with friends and begin to unwind and it's glorious. But then there's the return trip home. It always takes longer. It's like slogging through Chicago slush. Painful. Unpleasant. So, after years of dealing with this side of my personality, I've tried to develop a habit of articulating the positives of leaving.

I rise on the wrong side of the bed the day after spending time in contemplation and wonderment. It happens. I apologize to Spouse and try not to step on any toes. Rev. Crankypants is in the house.

So, to undo the crankyness, I want to thank Brother Rob for his kind attentions over the last few days. I want to thank him for letting me use his name in such a scandalous way as I have. His coattails are long. It's astonishing how using his name in such a title can bring traffic to one's blog. It's a little embarrassing, really.

Rob is a good man trying to do some radical stuff. He has a ministry to those who understand the call to be fully awake and alive in this world as a radical posture.

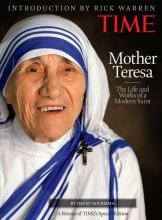

On Sept. 5, 1997, the world mourned when Mother Teresa, whose work with the poorest of the poor made her a global icon, died of a heart ailment at age 87.

Exactly 10 years later, the world did a double take, when a volume of Teresa's private letters revealed that the tireless, smiling nun spent the last 39 years of her life in internal agony. Jesus, she wrote, no longer seemed present to her, in prayer or even in the Eucharist. In letter after tormented letter she described an unrelenting spiritual "dryness,” a "torturing pain." Her smile was "a big cloak" of deception. She admitted at one point to doubting God's existence. Eventually she apparently became more reconciled to her condition; but as far as we know, she died with it.

As an 11-year-old boy, Don Bradley went looking for gold plates.

After all, Mormon founder Joseph Smith said he was directed to a set of such plates, buried in a hill near his house in upstate New York.

On a childhood visit to that hill, Bradley turned over lots of rocks, feeling certain he might find some sacred record overlooked by others.

That quest for Mormon gold became a metaphor for Bradley's lifelong spiritual journey. It led him first to dig into Smith's history to enhance his LDS devotion and then to uncover uncomfortable facts and omissions in the faith's story, which bred disillusionment and distance.

Eventually, Bradley's research helped bring him back to the Mormon fold, this time with a broader view of Smith's spiritual abilities.

"I could describe many of the events of Joseph Smith's life, but I couldn't explain the thing that really mattered: why it all worked," Bradley, now 42, said in a July speech at the annual Sunstone Symposium, a conference in Salt Lake City for Mormon intellectuals. "Joseph Smith wasn't of interest because he'd been a merchant, a mayor, or even a much-married husband, but because he was the founder of a religion. And it was precisely the religious dimension I couldn't account for."

Besides rediscovering Mormonism, Bradley learned how to balance faith and facts, science and spirituality, reason and revelation.