AT THANKSGIVING, MILLIONS of us across the country gather around tables. Gratitude will be expressed for blessings both great and small, which indeed is an opportunity to trace the goodness that enfolds our daily lives. Gratitude is one of the more ancient practices of our human society. It has long been observed across different religions, researched in the field of psychology, and mused over by philosophers. Orator and philosopher Marcus Tullius Cicero wrote, “Gratitude is not only the greatest of virtues, but the parent of all others.”

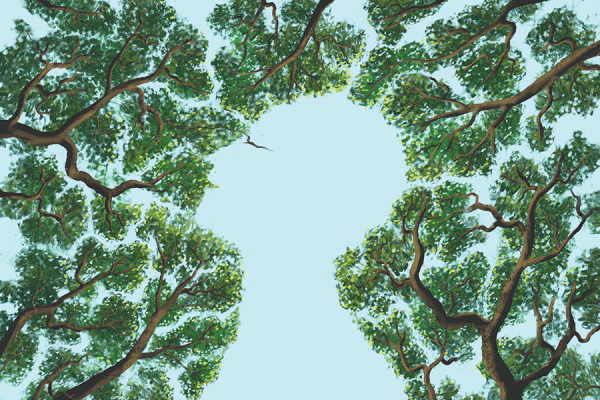

One of my most formative perspectives on gratitude comes from Indigenous practice. Indigenous cultures in the Americas have observed collective practices of gratitude that have long preceded our legislated day of thanks. The Haudenosaunee Confederacy, also known as the Iroquois or the Six Nations, have a daily Thanksgiving Address recited by school children just before classes begins. This is a practice author Robin Wall Kimmerer calls “an allegiance to gratitude.” The address uses gratitude to trace life-sustaining provision to the Creator, to the community, and to every food and water source, through every plant, every creature, and even the land itself. Gratitude is essentially ecological this way.

Read the Full Article