MY DREAMS ARE dominated by repairing the harms of mass incarceration. I dream of a future that includes decarceration and prison closures, one where Black people aren’t at risk of fatal police interactions. I dream of a future for Black people where public safety isn’t defined by arrests and lengthy prison terms. My Black future dreams are radical in the context of America. If my dreams were currently possible, the anti-Black through line that characterizes the nation’s public safety strategy would look a lot different.

Violent crime rates tripled between 1965 and 1990 in the United States, Germany, and Finland. Yet, countries have the policies and prison populations they choose. German politicians chose to hold the imprisonment rate flat. Finnish politicians chose to substantially reduce their imprisonment rate. American politicians chose to lengthen prison terms and send more people to prison. When migrant populations, some from the Global South, began moving into Germany and Finland, they were soon overrepresented in the prisons, incarcerated at twice the rate of citizens. Ethnic disparities and anti-Blackness drive incarceration policies everywhere.

Even in the context of increases in crime, the United States could choose another way. Public safety strategies could be centered on undoing the anti-Black practices that dominate criminal legal policies. Solutions must reduce the number of people imprisoned and strengthen communities rather than disappearing Black people from families and loved ones.

The Bureau of Justice Statistics reported recently that the number of persons under state and federal jurisdiction in 2020 had decreased by 25 percent since 2009 (the year the number of prisoners in the U.S. peaked). However, the nation’s overall prison population grew by 700 percent between 1972 and 2009. As of 2020, the combined state and federal imprisonment rate in the U.S. was 358 per 100,000. By comparison, Germany’s incarceration rate was 72 per 100,000 and Finland’s was 53.

To meaningfully address mass incarceration, steps must be taken to counter the anti-Blackness that dominates the nation’s criminal legal system. Research shows that excessive sentencing laws for certain offenses disadvantage Black defendants because sentencing laws interact with broader racial differences in society and within the legal system itself, such as prosecutorial racial bias.

Recent policy changes suggest that lawmakers and community stakeholders are continuing efforts to scale back mass incarceration. Last year, several states adopted criminal legal reforms. California lawmakers adopted legislation to restrict practices that make prison time longer for alleged gang crimes. Colorado reclassified felony homicide offenses from first-degree murder to second-degree murder when a death is not caused by the defendant. Virginia lawmakers abolished the death penalty.

So much more can be done to reimagine the nation’s response to crime in support of public safety. First, we must reorient the nation’s criminal legal codes around a 20-year maximum prison sentence, except in unusual cases, with an emphasis on rehabilitation and a mechanism to evaluate the risk to public safety of some prisoners as they reach the end of their term. Norway caps prison terms at 21 years, even for the most severe crimes, and has the lowest recidivism rate in Europe. The 21-year-old lookout in an armed robbery that resulted in a homicide may be a very different person at age 42.

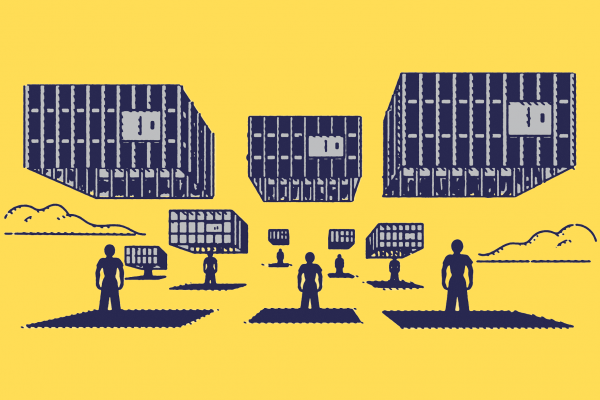

Second, we must focus resources to strengthen effective remedies in high- incarceration communities. Studies show that community-level approaches that address underlying causes and strengthen ties and investments in community relationships can be effective at reducing crime both by creating opportunity and by enhancing informal social control mechanisms. Third, we must reimagine prison itself, with an eye toward eventually decommissioning prisons and repurposing them for noncorrectional uses.

Dreaming of a Black future offers an opportunity to undo the extreme sentencing practices. My dream is that 20 years from now we’ll see a substantially lower prison population and full funding of preventive solutions that reduce contact with the criminal legal system.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!