In a world far removed from the tragic cesspool of Washington scheming and maneuvering, real people flocked to Central Park on El Camino Real for this town’s first Bacon & Brew Festival.

It was wildly successful. Vendors ran out of food and beverages; sponsors closed off ticket sales early. The parched and mean-spirited landscape that ideologues are trying to manufacture seemed distant.

As they stood in line for burgers, barbecue, fries smothered in cheese, and microbrewed beers, young adults eyed each other’s pregnant bulges and baby strollers. I heard no muttering about Obamacare. People have better things to do than to defund a program that benefits fellow citizens.

Yoo-hoo! Sarah Silverman, Jon Stewart, Larry David! No matter how unreligious you comics may be, American Jews seem proud to claim you.

Well, mostly. You know the joke: Two Jews, three opinions…

But seriously: A sweeping new survey from the Pew Research Center, “Portrait of Jewish Americans,” finds humor is one of the main qualities that four in 10 of the nation’s 5.3 million religious and cultural Jews say is essential to their Jewish identity. The survey was released Tuesday.

The top religion story of 2012 was the “rise of the ‘Nones’” — the one in five adults in the U.S. eschewing any religious label. That trend is now evidenced across the American religious spectrum, including in Jewish communities. About 22 percent of Jews now describe themselves as having no religion, according to a new Pew Research Center survey of U.S. Jews.

“Fully a fifth today of Jews in the United States are people who say they have no religion. They’re atheists, agnostics, or, the largest single subgroup, nothing in particular,” said Alan Cooperman, co-author of the study.

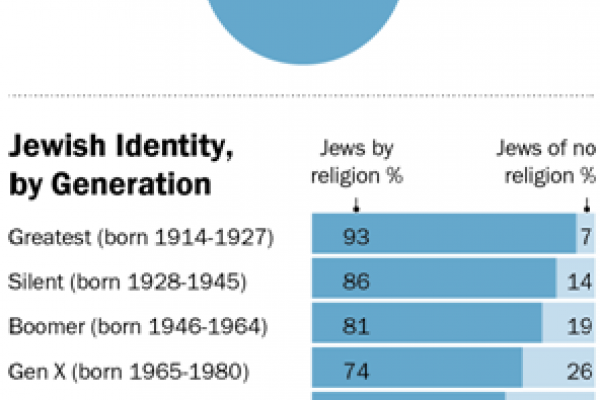

The trend of disaffiliation mimics that of other backgrounds, particularly by age. For example, 93 percent of Greatest Generation Jews (those born between 1914 and 1947) identified as being Jewish by religion, while only 68 percent of Millennial Jews (those born after 1980) say the same.

After reciting what we call the Lord’s prayer one Sunday, I got to thinking about how many times I’d said those words. Thousands? But how many times have I actually thought about what the words mean?

If we pay attention, it’s a prayer that makes us very uncomfortable.* These words of a peasant Jewish rabbi from 2,000 years ago challenge so much about the way we live — all of us, regardless of what religion we follow. If we’re honest, most of us don’t like it and have no intention of living by what it says.

Which presents a question: Isn’t it a problem if we pray one way and live another? Shouldn’t our prayers reflect how we actually try to live?

Along those lines, perhaps we should rewrite the Lord’s prayer and make it conform to what we really believe. In that spirit, here’s a rough draft of what it might sound like if the Lord‘s prayer was actually our prayer.

WASHINGTON — In the most comprehensive study of American Jews in 12 years, a strong majority said being Jewish is mostly about ancestry or culture, not the religious practice of Judaism.

“A Portrait of Jewish Americans,” released Tuesday by the Pew Research Center, shows strong secularist trends most clearly seen in one finding: 62 percent of U.S. Jews said Jewishness is largely about culture or ancestry; just 15 percent said it’s about religious belief.

“Non-Jews may be stunned by it,” said Alan Cooperman, co-author of the study. “Being Jewish to most Jews in America today is not a matter of religion.”

The federal government began shutting down overnight, for the first time since 1996, after Congress failed to compromise on how to fund federal agencies — battling instead over implementation of the Affordable Care Act.

From The Washington Post:

The impasse means 800,000 federal workers will be furloughed Tuesday. National parks, monuments and museums, as well as most federal offices, will close. Tens of thousands of air-traffic controllers, prison guards and Border Patrol agents will be required to serve without pay. And many congressional hearings — including one scheduled for Tuesday on last month’s Washington Navy Yard shootings — will be postponed.

Faith leaders on Monday called on Congress to end partisan brinkmanship and consider the real damage their actions have on the American people.

Christians and Jews are mounting campaigns for and against a path to sainthood for British writer G.K. Chesterton (1874-1936), one of the world’s best-known Catholic converts.

Roman Catholic Bishop Peter Doyle of Northampton, where Chesterton lived and worked, has ordered an examination of Chesterton’s life — the first step in what is likely to be a long and unpredictable process toward canonization.