Mar 26, 2025

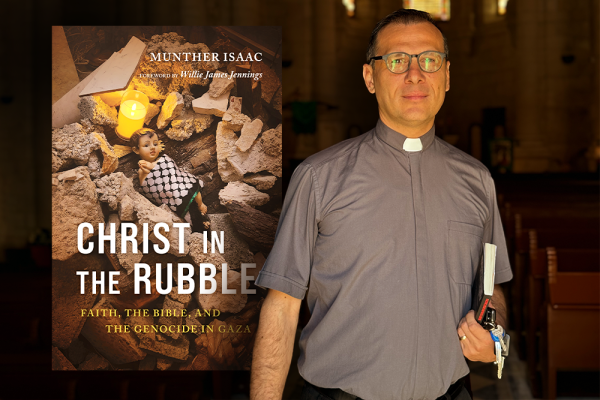

In ‘Christ in the Rubble,’ Palestinian pastor Rev. Munther Isaac surveys the devastation of his homeland and finds God in the most unexpected places.

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login

In ‘Christ in the Rubble,’ Palestinian pastor Rev. Munther Isaac surveys the devastation of his homeland and finds God in the most unexpected places.