Mar 6, 2024

As racist ideas continue to plague U.S. politics, Mark Doox’s Afro-surrealist and satirical graphic novel, The N-Word of God, couldn’t have arrived at a better time.

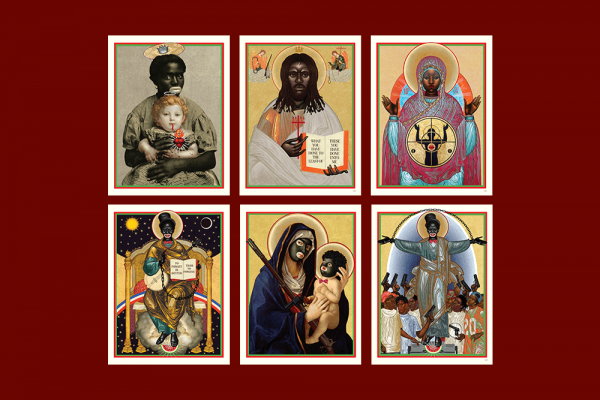

The book is a visual novel told through depictions of anti-Black images — Black people eating watermelons, Jim Crow caricatures, mammies, and blackface — all stylized in the form of Eastern Christian iconography. This is a style that Doox has termed “Byzantine Dadaism.” Doox’s novel deconstructively takes these caricatures that have historically harmed Black people and reimagines them as symbols of Black resilience and healing, restoring the inherent dignity that belongs to every human being, especially those who have been racialized and subjugated by U.S. anti-Blackness.

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login