Oct 18, 2023

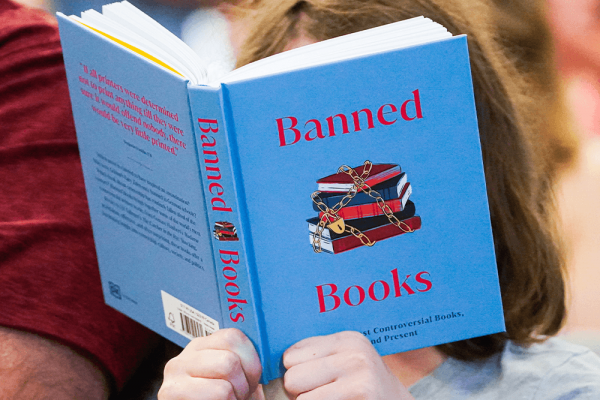

Book-banning has always been about censoring the stories, histories, and information that push us to question the status quo.

Read the Full Article

Already a subscriber? Login

Book-banning has always been about censoring the stories, histories, and information that push us to question the status quo.