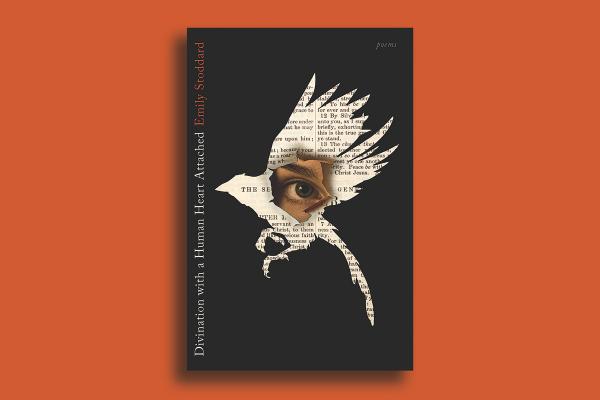

IN EARLY CHRISTIAN gnostic texts, you can read the story of St. Peter’s daughter, who would come to be known as Petronilla. Legend has it that Petronilla was so beautiful that her father prayed she be paralyzed on one side (so that she would not “be beguiled”). In Emily Stoddard’s debut collection of poetry, Divination with a Human Heart Attached, Petronilla is a fruitful companion and the voice of several poems. They appear alongside poems voiced by a contemporary speaker who we assume to be Stoddard herself. In this way, Petronilla serves as a sort of spiritual ancestor for Stoddard. Both look for and lose faith. Both find signs of divine presence everywhere.

While Petronilla’s God speaks in things like “fish and flower,” Stoddard’s confessional work finds God in interior, negative space — not in religious institutions: “I cut away from my body ... slice myself awake to numb arms ... too big to fit inside the church.” She tentatively hopes that “if it’s true, if god is there at all, she kicks us from the inside.” Faith finds form here in ovaries, dreams, the “dark joy” of Stoddard’s dying grandmother finding beauty in “the sunset on the highway.” Unlike Petronilla, whose father fears her seduction by men, the poet-speaker is seduced by poetry — the power of naming things “without the restraint of a scientist.” Names for plants, names for God: “we are not done yet / inventing names / for what will save us.”

Read the Full Article