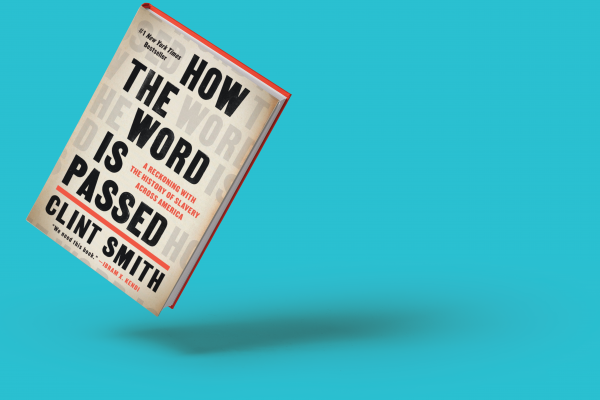

THE STATUE OF Liberty, author Clint Smith tells us, was supposed to celebrate the abolition of slavery. Early models depicted the iconic copper lady holding a raised torch in one hand and a pair of broken shackles in the other, but the final version included only a piece of broken chain at the lady’s feet. With slavery shifted to the periphery, Ellis Island’s visitors could imagine liberty was, and is, possible without abolition.

In How the Word Is Passed, Smith visits multiple historic sites to offer a mosaic portrait of how different places tell, or do not tell, the truth about slavery. The book meditates on the capacity of our collective symbolic infrastructure to prepare us to rectify persistent material inequalities. If we frame slavery as something that “happened a long time ago” or leave unchallenged the warping of the Confederate commitment to enslavement into myths of honor and heritage—if, in a word, we misremember the wound—then we will not summon the will nor the proper know-how to heal it.

Read the Full Article