EXCEPT FOR ABRAHAM LINCOLN and Thomas Jefferson, every president of the United States was or is a professing Christian.

Only in the case of John F. Kennedy, it seems, has a president’s Christian faith counted against him in the opinion of a significant number of citizens, and in Kennedy’s case it was because he was Catholic rather than Protestant. The Christian belief of public officials in any branch of national, state, or local government hardly ever raises concern among the U.S. public. But the opposite is true when it comes to Muslim officials.

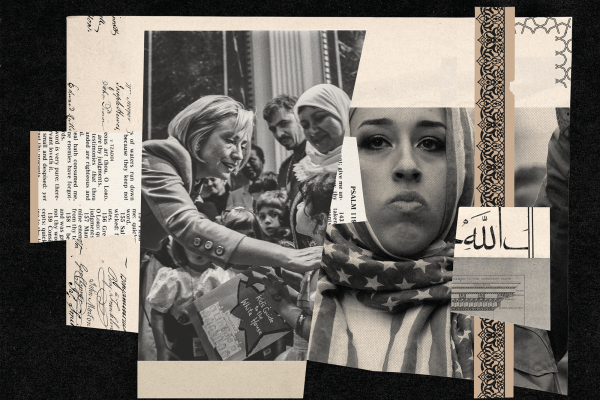

Many conservative Americans say they fear that the U.S. will become a nation influenced by Islamic tenets instead of Christian ones. Commentators on Fox News often express alarm about sharia (Islamic law). Jeanine Pirro, host of the network’s Justice with Jeanine Pirro, accused Rep. Ilhan Omar, D-Minn., a Muslim woman of Somali descent, of supporting Islamic rule in the United States. Omar and Rep. Rashida Tlaib of Michigan are the only two Muslim women ever elected to Congress, and two of the three Muslims ever to serve in the U.S. legislature; Twitter users criticized Omar for wearing a hijab and Tlaib for wearing, at her congressional swearing-in, a traditional Palestinian dress called a thobe, made by her mother. Another Fox News host, Pete Hegseth, said that, based on how Tlaib “talked about President Trump having a hate agenda, I could, therefore, look at her and say that she has a Hamas agenda.” The Associated Press had to debunk the claim that Tlaib’s thobe was a “symbol of Hamas terrorists,” a sign that many Americans may have believed it to be true.

The alienation and hate go even further. A Florida Republican politician said in a fundraising email that falsely claimed that Omar worked for the nation of Qatar, “We should hang these traitors where they stand.” Another man called Omar’s office and said he would “put a bullet in her skull.” Following the Jan. 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, when lawmakers were still in the building trying to certify President Joe Biden’s election, Tlaib discussed on the House floor her constant fear due to the death threats she regularly receives.

“I worry,” she said, “every day.”

The demonization of Islam

JEFFERSON, THIRD PRESIDENT and key author of the Declaration of Independence, wrote in the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom that “proscribing any citizen as unworthy the public confidence by laying upon him an incapacity of being called to offices of trust and emolument, unless he profess or renounce this or that religious opinion, is depriving him injuriously of those privileges and advantages to which, in common with his fellow citizens, he has a natural right.” (At the time, women were barred from public office.)

As Tlaib’s swearing-in to Congress neared, she planned to place her left hand on Jefferson’s 1734 edition of the Quran, just as Keith Ellison, the first Muslim to be elected to Congress and now attorney general of Minnesota, had done years before. “It’s important to me,” Tlaib said, “because a lot of Americans have this kind of feeling that Islam is somehow foreign to American history. Some of our Founding Fathers knew more about Islam than some members of Congress now.”

But the day before her ceremony, a Washington Post investigation into the history of Jefferson’s Quran revealed that George Sale, the British scholar who translated the book, did the translation so that Protestant Christian missionaries traveling to Muslim nations would be able, in Sale’s words, to “attack the Korân with success”—in other words, to convert Muslims to Christianity, to eliminate their Islamic belief.

Tlaib decided to forego swearing in on Jefferson’s Quran and placed her left hand on her own copy of the holy text instead.

In the West, “we somehow think about Islam as different from all other religions,” said Sylvia Chan-Malik, a scholar of the history of Islam in the United States and an associate professor in the American and Women’s and Gender Studies departments at Rutgers University. “Jewish Americans, Christians, Buddhists, Hindus: We do not think of them as somehow in lockstep, being fueled somehow, magically or very viscerally, through their holy texts,” Chan-Malik told Sojourners. “Whereas Muslims are seen in that way, and that is, in my estimation, a configuration of all of these factors around race, around religion, around certain notions of gendered Muslim bodies.” In North America, according to Chan-Malik, Islam and race are connected because “anywhere from one-tenth to one-third of enslaved Africans in this country were Muslim.”

Alaina Morgan, also a scholar of the history of Islam and an assistant professor of history at the University of Southern California, told Sojourners that bias against Muslims goes even further back in history. “The demonization of Islam and the othering of Islam, the orientalization of it, really goes back to the medieval period,” Morgan said. If you “look at illuminated texts and stained glass and psalters, songbooks, you’ll see things like a crusading army invading, and the people that they are fighting, Muslims, looking just grotesque, extremely dark-skinned in comparison to [the crusading army] looking light and angelic.”

Faith in the public sphere

THIS DEMONIZATION AND racializing of Islam echoes to the present, with Islamophobic vitriol often aimed at African Americans, immigrants, and other people of color. Some white Americans, for instance, still claim that Barack Obama, the nation’s first African American president, couldn’t possibly be Christian, insisting that he’s Muslim. In 2018, now-Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, a Republican from Georgia, also proclaimed that Obama was “secretly” Muslim, and in 2020 she posted on the Facebook page for her congressional campaign a picture of herself holding a gun beside Omar, Tlaib, and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York (who’s Catholic), with the caption: “We need strong conservative Christians to go on the offense against these socialists who want to rip our country apart.” Greene is still a member of Congress.

Questions of how religious people should bring their faith into the public sphere were on Obama’s mind when he was a U.S. senator. In 2006, two years before his historic election to the presidency, he spoke about these issues at a conference co-hosted by Sojourners.

“[S]ecularists are wrong when they ask believers to leave their religion at the door before entering the public square,” Obama said. He cited the faith-based moral language of Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, William Jennings Bryan, Dorothy Day, and Martin Luther King Jr., all of whom played a part in the ongoing push for equal rights for all members of the citizenry.

And yet, said Obama, “Democracy demands that the religiously motivated translate their concerns into universal, rather than religion-specific, values. ... Now this is going to be difficult for some who believe in the inerrancy of the Bible, as many evangelicals do. But in a pluralistic democracy, we have no choice. Politics depends on our ability to persuade each other of common aims based on a common reality. It involves the compromise, the art of what’s possible. At some fundamental level, religion does not allow for compromise. It’s the art of the impossible.”

But Rachel Laser, CEO of Americans United for Separation of Church and State and the organization’s first female and first Jewish leader, believes compromise is attainable. “We don’t want to ask anybody to strip themselves of who they are when they serve in office,” Laser told Sojourners. “But at the same time, you want to make sure that when people become political leaders in America, they understand that they’re representing all people’s interests, not just the interests of some. ... Our laws protect everybody’s right equally to believe or not as they see fit, as long as they don’t harm others.” Americans United, according to Laser, doesn’t just work to win legal battles but also seeks to educate the American citizenry that the separation of church and state “strengthens religion.”

Education, Morgan believes, could also establish collective knowledge of Islam in the U.S., undoing misinformation people have about Muslims. That would likely bring the nation closer to the religious tolerance Jefferson envisioned.

Respecting people of all religions

“FOR MANY AMERICANS,” said Morgan, “when they think about Islam, they think about Malcolm X, and then they think about 9/11 ... and it really has to do with the lack of great education on the subject, and the Christian bias, quite frankly, in education.”

It’s not commonly taught in U.S. public schools that, to quote the historian Sam Haselby, “Muslims were living in America not only before Protestants, but before Protestantism existed. After Catholicism, Islam was the second monotheistic religion in the Americas.” That makes the presence of Muslims in the U.S. government, and the election of Muslims to public offices, long overdue.

“In terms of political enfranchisement and participation,” said Chan-Malik, “I do see that there’s been an incredible push in young Muslim communities that are very much being politicized and coming of age within the Black Lives Matter generation. They are starting to see these types of narratives and histories becoming more accessible. There are websites, there are places to access. Whether they’re from Pakistan or Bangladesh or Indonesia or Egypt, they’re starting to see that Islam does have a particular narrative in the United States that is rooted in Black liberation struggles, that’s rooted in anti-colonialism, that has this particular power to it.” Emgage, a nonprofit that seeks to boost the political knowledge and abilities of Muslims in the U.S., estimated that 100 Muslim Americans filed to run for public office in 2018.

Republican Ben Carson, during his 2016 presidential campaign, said, “I would not advocate that we put a Muslim in charge of this nation.” In response, Yusuf Dafur, then 12 years old, said in a video he asked his mom to post on Facebook: “Obama already broke that Black people boundary,” the bias keeping African American people from sitting behind the Resolute desk, “and I will break that Muslim boundary. I will become the first Muslim president, and you will see that when I become president, I will respect people of all faiths, all colors, and all religions.”

When Obama was elected president in 2008, the nation that had emerged from the Declaration penned by Thomas Jefferson did not shatter. Obama’s Blackness did not mar the role he assumed, and neither will anyone’s Muslim identity.

How long will it take for America to understand this? Will it take until 2038, when Dafur will turn 35, the minimum age for a U.S. citizen to run for the country’s highest office? How long will it take for the virtues of equity and openness touted in our founding documents to take precedence in our modern politics?

Perhaps, to paraphrase Dafur, “We will see.”

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!